And the 2023 Economics Nobel Goes to...

Claudia Goldin for "for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes"

To the delight of many and very little surprise, the Real Nobel Prize was awarded this morning to Claudia Goldin.

If there is one consistency across Goldin’s wide-ranging work, I’d say it is supply and demand. Yes, I say supply and demand is the one thing for Goldin, but I say supply and demand is the one thing for everything.

But it’s not just me! As the Nobel’s Scientific Background points out:

Goldin’s application of this demand-and-supply framework thus provides a consistent lens through which changing female labor market outcomes can be understood. Labor market gender gaps can be explained by economic fundamentals, and the constraints facing women are central in this framework.

Yet, to truly appreciate her contributions, one must dive deep into her comprehensive body of work. Unlike last year's prize, where half of it focused on a single model of bank runs, Goldin's legacy sprawls over decades of research. If you look at her citations, you don’t see one HUGE paper. You see decades worth of hard work. There’s generally a bias against this work for the Nobel, compared to one flash of insight, and Claudia’s work probably has something to say about that…

Here are a few pieces to start learning about Claudia Goldin’s research.

The Power of the Pill

Goldin's paper with Lawrence Katz on oral contraceptives is a perfect starting point, not only because of the pill’s ubiquitous nature but also due to its profound influence on women's life choices. By granting reproductive autonomy, the pill revolutionized educational and career paths for women. This paper showcases Goldin's unique approach by presenting a “collage of evidence,” as she describes it. No single graph can encapsulate her thesis.

While the paper is relatively accessible (for economics research), it is a serious paper with lots of econometrics, so it may not be for everyone. Luckily, this piece has a great video explaining it from Marginal Revolution University.

The Quiet Revolution

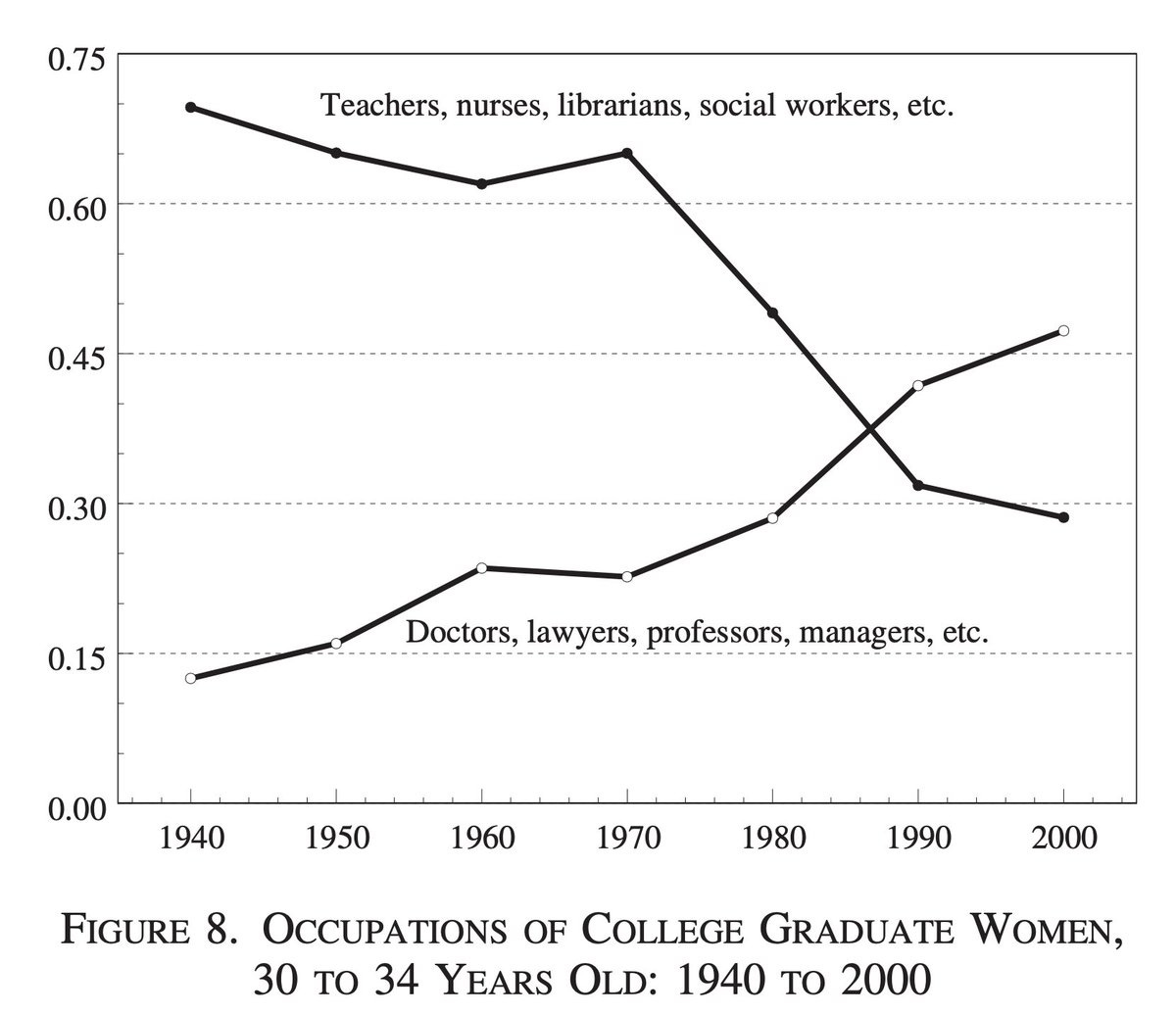

In her Ely Lecture, Goldin documents the societal shifts post-1970s, where women began to:

Prioritize higher education and professional careers.

Delay traditional milestones like marriage and motherhood.

Place a stronger focus on establishing careers before families.

One key factor in this revolution was the changing nature of jobs. Goldin and Katz have other great papers on the importance of technological change. Occupations became less about physical attributes and more about cognitive skills and education, opening doors for women.

The revolution wasn't just about external, technological shocks. Goldin traces out how technology interacted with women’s expectations about what their options would be. Choice is deeply subjective and depends on what people believe to be possible. Usually, this point is made in economics classes but then ultimately abandoned because it is hard to empirically estimate, but Goldin does. Women began to see themselves differently, leading to a change in their personal narratives and long-term aspirations. This drove the jobs women pursued.

Importantly, "The Quiet Revolution" wasn't quiet because it was subtle. It was "quiet" because it was a profound internal transformation in women's self-perception and goals, more than just visible societal changes.

A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter

This 2014 paper, Goldin’s most cited paper, is where Goldin turns her gaze towards the future. As a historian, she, of course, does that by looking at the past. Goldin argues that the current gender wage gap isn't about differences between genders when they reach the labor market. It is not about human capital differences. After all, women are much more likely to graduate college.

Instead, the remaining gap can be attributed to how the labor market rewards and punishes certain attributes, like working long hours or needing flexibility. Some positions have a highly nonlinear pay structure. Those who work the longest, are the most skilled, do not just get paid a little more than the rest but A LOT more.

This paper has taken on a new interest in my eyes with the shift to remote work. The work-from-home transition can either be a great equalizer or widen existing divides. Work from home could be an equalizer in that previously inflexible jobs that women were deterred from could become slightly more flexible, attracting more women. At the same time, solve for the equilibrium. If many workers want to work from home, there could be additional compensating differentials, driving up the wages for those who are more willing to deal with the inflexibility (traditionally men). These equilibrium questions are what Goldin spends much of the paper focused on, which is great to see as a fan of price theory.

Final Thoughts

Summarizing Goldin's work is an arduous task, primarily because her insights, as is typical of economic historians, are spread across multiple articles and books. I didn’t even mention the books! Her most cited work is relatively recent. My conjecture is that it is because those papers represent a culmination of years of study. This stands in contrast to a more-typically-male form of genius like one sees in some mathematical insight generated as a 20-year-old grad student.

As always, Marginal Revolution is the place to be for more Nobel info.

The Nobel's "Scientific Background" offers a serious summary but takes some time. The intro is worth everyone reading (6 pages). I’m more skeptical suggesting the Nobel's "Popular Background, " since I’m not convinced it tells us about Goldin’s specific insights. The prize is not for documenting a wage gap or for showing women’s labor force participation changes over time. Her holistic, historical approach to studying labor markets is the contribution. In that way, this is an economic history prize, even if not explicitly stated.

Also, the most badass part of the prize may be that she released an NBER paper titled “Why Women Won,” hours before. This is a coincidence based on the timing of NBER and the prize but I can’t help but smile.