And the 2025 Economics Nobel Goes to...

Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt "for having explained innovation-driven economic growth"

There are years when the Nobel prize in economics is good, years it is bad, and years it is outstanding. This year is outstanding. This is the prize I’ve been waiting for. Not because I predicted it or had money riding on it, but because it recognizes work that tackles THE question: Why did we get rich?

The 2025 Economics Nobel went to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.”

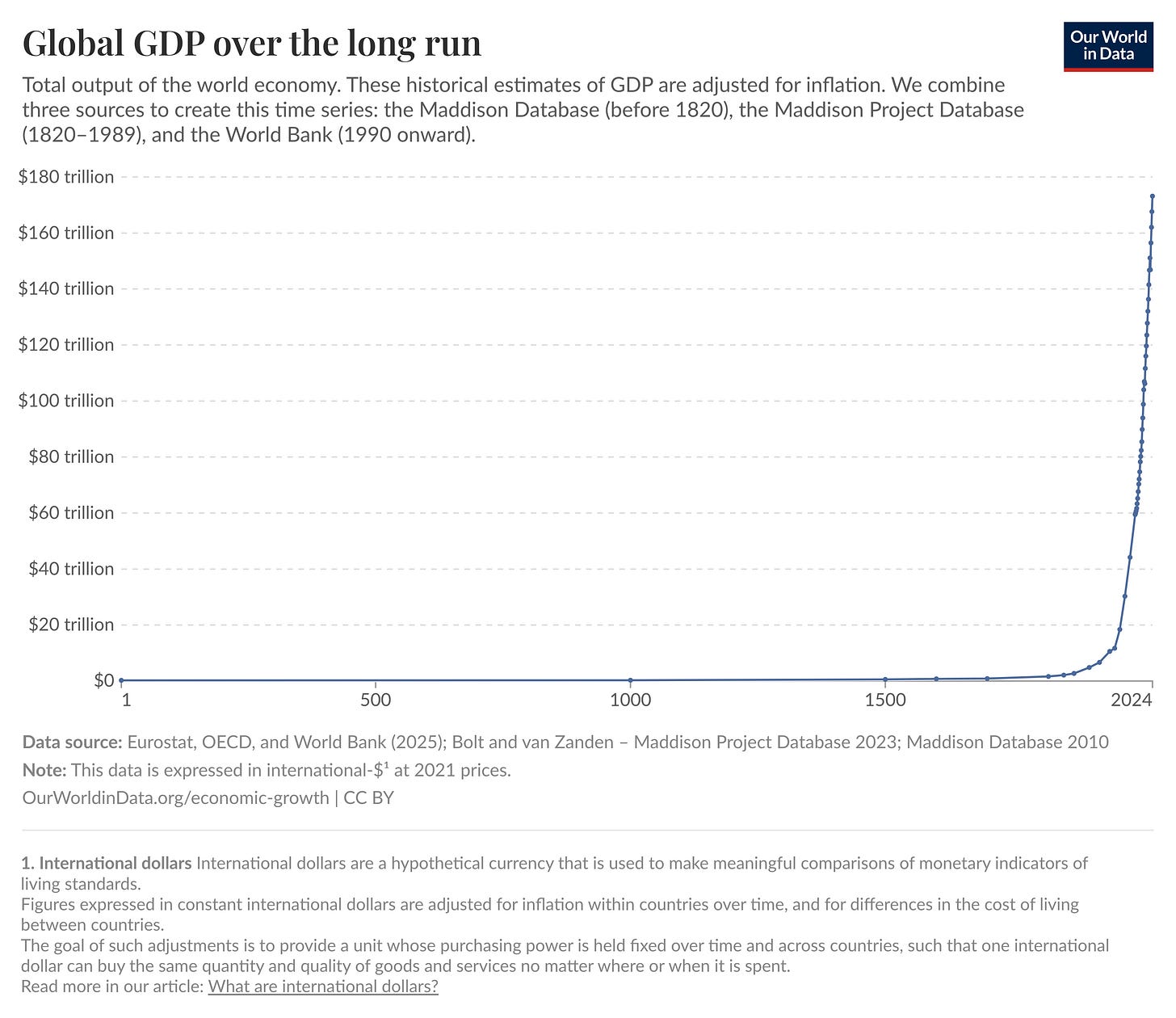

The biggest question in economics is the hockey stick. For most of human history, living standards barely budged. Then something shifted. We got the hockey stick. Why did this happen? When? What made it possible? Many economics papers are small. Many of my papers are small. But not this work.

This prize splits among two different contributions. Mokyr gets half for explaining the prerequisites—what conditions needed to exist before sustained growth could happen in the first place. Aghion and Howitt share the other half for building the workhorse model of how innovation actually drives growth once those conditions are met. It’s history meets theory. Last year’s prize was history and theory but this is actually history. And that’s how economics should work.

The Intellectual Origins of Economic Growth

Mokyr, compared to the other two, really won for a body of work on the topic. Mokyr’s research program spans decades and fills multiple books, so it’s not simple to say what his argument is. To understand his argument, you need to trace its development across his major works.

His most cited work (maybe because it was earlier) is The Lever of Riches (1990), where he established the framework by asking why technological progress occurs at all. Mokyr argued that neither demand-pull nor supply-push theories alone could explain innovation patterns. Instead, he introduced the concept of “macroinventions” (radical breakthroughs) versus “microinventions” (incremental improvements), showing how both were necessary and how their relative importance varied across societies and eras.

In The Gifts of Athena, Mokyr develops his central analytical distinction. There are two types of “useful knowledge” necessary for innovation:

First, there’s propositional knowledge, understanding why things work. The scientific or theoretical principles behind natural phenomena. This includes mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, what Mokyr calls the “epistemic base.” Think of it as “knowing that.” This is the science stuff, understanding that air has weight and pressure, knowing the principles of combustion, recognizing that diseases spread through microorganisms.

Then there’s a more applied level, prescriptive knowledge, knowing how to make things work in practice. The techniques, recipes, and hands-on mastery of production. Think of it as “knowing how.” This is the millwright’s method for building a waterwheel, a brewer’s recipe for fermentation, a weaver’s technique for operating a power loom.

For most of history, these existed in separate worlds. Scholars developed propositional knowledge (natural philosophy, mathematics) largely divorced from practical applications. Meanwhile, craftspeople innovated through trial-and-error without scientific guidance. The knowledge of why something worked often remained mysterious even to those who made it work.

In that world, innovation was hit-or-miss and rarely cumulative. Many supposed breakthroughs were dead ends. The Industrial Revolution became a true turning point only when propositional and prescriptive knowledge started reinforcing each other. This tightening feedback loop is what made growth sustained rather than one-off. In earlier eras, a brilliant invention might boost productivity temporarily, but without scientific foundations to build upon, the advance eventually stalled.

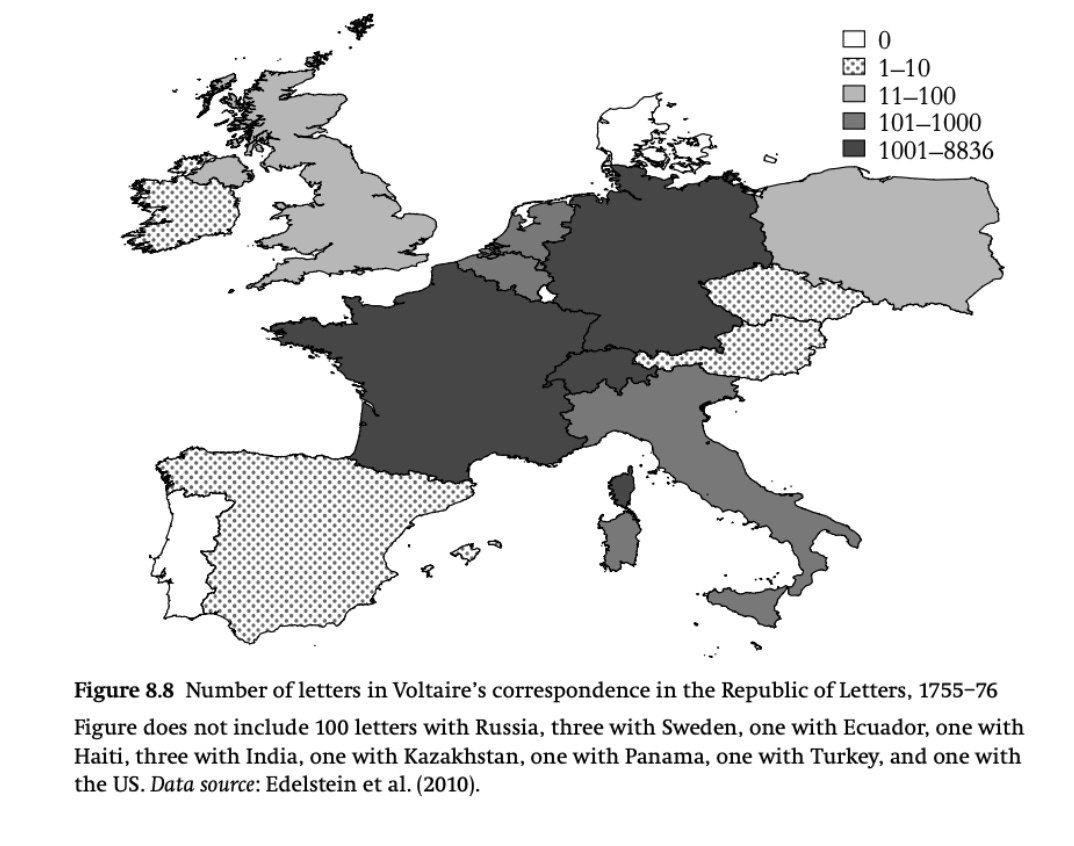

But Mokyr goes deeper. Why did this feedback loop start in Europe around 1700? His answer is institutional: the Republic of Letters.

This was an early-modern, pan-European market for ideas. Low barriers to entry. Peer criticism. Prizes and journals for sharing discoveries. Competition between scholars across different countries. If one monarch shut down your research, you could move somewhere else and keep working.

That’s still a little vague. How do we actually see that in practice?

Mokyr (2009, 2016) talks about “The Republic of Letters.” It was a Europe-wide network where intellectuals shared ideas, tested theories, and developed standards for what counted as good science.

Voltaire didn’t just correspond with people in Paris. He exchanged letters with thinkers across England, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and beyond. It created a hierarchy based on merit, not social status. Bad ideas got weeded out. Good ideas spread.

This matters because in most societies throughout history, brilliant minds worked alone. Leonardo da Vinci was a genius, but he was isolated. Or innovators depended on royal patronage, which meant they could be silenced if they offended the wrong person. The Republic of Letters solved both problems.

This happened first in Europe, which had a unique combination: cultural unity with political fragmentation.

Cultural unity meant that ideas could spread. A postal network linking all of Europe made continuous correspondence possible. Scientists in London could build on work done in Paris or Amsterdam. Political fragmentation meant that heretical thinkers had escape routes. When the Counter-Reformation became dominant in Southern Europe after 1600, innovative thinkers could flee to more tolerant jurisdictions. Descartes and Pierre Bayle left France. Hobbes and Locke left England at different times. No single authority could suppress new ideas across the continent.

This combination was rare. China had political unity but no escape valve for heterodox ideas. The Middle East and India had political fragmentation but lacked the cultural unity and infrastructure to spread ideas effectively.

The Republic of Letters was pan-European. So why did industrialization happen in Britain?

Mokyr argues it was because Britain had something most other places lacked: a large population of highly skilled craftsmen, artisans, and tinkerers. These people could take abstract scientific ideas and turn them into practical innovations. This ties back to the earlier ideas about the different types of knowledge.

When the scientific revolution produced new knowledge about physics, chemistry, and mechanics, British skilled workers were ready to use it. They had the practical skills. They also internalized a key Enlightenment idea: that the world could be improved through human effort.

This is too short a space to do justice to Mokyr. The prize recognizes not individual papers but an intellectual program spanning four decades that fundamentally reshaped how economists think about long-run prosperity.

Suppose one had to summarize Mokyr’s career-long contribution in a sentence. In that case, it might be: Sustained economic growth stems from systems that continuously generate, diffuse, and apply useful knowledge, and those systems require specific cultural and institutional prerequisites that are neither natural nor automatic.

This might sound abstract, but Mokyr’s genius lies in making it concrete through rich historical detail.

The Puzzle of Smooth Growth and Wild Churn

On the opposite side of historical details is theory (although Mokyr himself is grounded in theory and had early papers with formal models of growth).

This is where Aghion and Howitt come in. Their 1992 paper “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction” is now the workhorse model of endogenous growth (sorry Romer). I say “workhorse” because it’s become the baseline framework that researchers extend, modify, and test against data.

I give a talk on competition where I explain two facts:

First, economic growth in places like the United States is remarkably consistent. If I showed you decade-by-decade real GDP growth and removed the labels, you couldn’t tell the 1950s from the 1980s (maybe you’d spot the 2000s because of the financial crisis, but that’s it). Draw a line through real GDP per capita from 1950 to 2020, and it’s remarkably smooth. About 2% per year, give or take. Steady. Predictable. Boring, even.

Second, underneath that smooth aggregate growth is massive creative destruction. We had almost 8 million jobs created in the last quarter of 2024. Think about that number. Eight million new employment relationships formed in three months. But here’s the kicker: we also had over 7 million jobs destroyed in that same period. Firms constantly enter and exit. Workers move between employers. Products get launched and discontinued. The labor market churns.

The Business Dynamics Statistics from the Census Bureau tell an even more striking story. In a typical year, about 10% of establishments close. Another 10% open. The job creation rate hovers around 15% of total employment. The job destruction rate is similar. Every five years, roughly half of all jobs turn over. Ryan Decker and co-authors documented that this dynamism was even higher in the 1980s and 1990s. These numbers were falling before the pandemic but are still crazy high. (Side-bar: they’ve ticked back up.) The smoothness in aggregate growth existed alongside even wilder churn at the micro level.

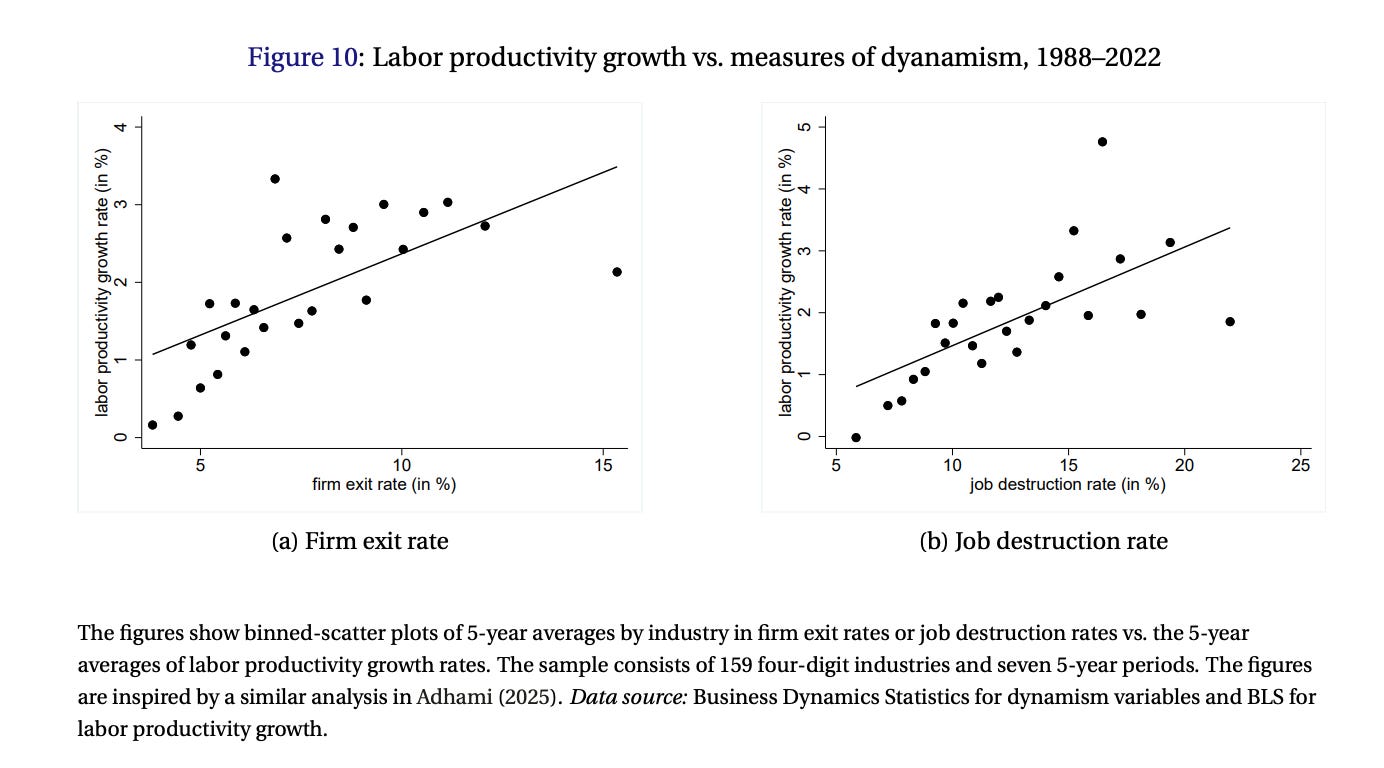

This is a huge part of economic growth. There are different decompositions but Baqaee and Farhi (2020) find about half of aggregate U.S. total factor productivity growth over the period 1997–2015 is due to the reallocation of production factors from low to high revenue productivity firms. The scientific material shows this at an industry level.

Back to the two facts: How do you get a smooth growth path when the underlying economy is so turbulent? This is THE puzzle that Aghion and Howitt solve. Their original 1992 paper isn’t completely couched in these terms. The data wasn’t well developed yet which is why I’m a bit bummed John Haltiwanger couldn’t share this prize with Aghion and Howitt for developing this data. But the committee is right to point out that this is the key question underlying a model of creative destruction.

Their answer: innovations arrive at random times in different sectors, like raindrops. In any single sector, you get sudden jumps when breakthroughs happen. Netflix enters and destroys Blockbuster’s profits essentially overnight. The iPhone launches, and BlackBerry’s market share collapses. Creative destruction is violent and discontinuous in a single industry at a single moment.

But the economy has thousands of sectors. At any given time, some sectors are experiencing breakthroughs while others are stable. The jumps don’t happen simultaneously across all industries. They’re staggered, random, uncorrelated.

Across thousands of sectors, those jumps average out. It’s the law of large numbers. The aggregate growth rate becomes:

growth ≈ (size of each quality step) × (how often steps arrive across all sectors)

That’s where growth comes from in their model. It’s elegant. It explains the macro smoothness and the micro volatility.

Schumpeter and Profits

Taking Schumpeter seriously also changes how we think about competition, one of my favorite areas. Standard Econ 101 models wrongly imagine markets with stable sets of firms. Maybe new firms can enter, but we often treat the number of firms as fixed. That’s not remotely close to reality. We have immense churn. I’ve written elsewhere that this reallocation, creative destruction, is the essence of competition and how we should measure it.

In an Aghion-Howitt style model, the markup—how much profit a leader can charge—ties mechanically to the quality step. If your product is 10% better than the competition, you can charge a limited markup. If it’s twice as good, you can charge more.

This gives you a microfoundation for variable markups across firms. In my writing on markups, I’ve emphasized that we can’t just look at the markup level and conclude markets are uncompetitive. Markups can rise because firms improved their products. That’s good! The markup reflects the gap between your quality and the next-best option.

Aghion-Howitt formalizes this intuition. Markups/profits are the incentive for innovation. If you couldn’t earn a markup by innovating, why bother investing in R&D?

But—and this is crucial—those markups are temporary in their model. Other firms keep innovating. Eventually, someone leapfrogs you, your markup disappears, and you’re back to competing or exiting. Competition happens through innovation, not just price-cutting. This ties back to the dynamism point. This is a different view of competition than in standard models. In the basic IO model, firms compete by lowering prices toward marginal cost. In Aghion-Howitt, firms compete by trying to climb the quality ladder. The winner gets high markups for a while. Then the next innovator takes over.

These complications motivated a paper of mine with Ryan Decker. Many people look to the dynamism slowdown and blame market power. (More explicitly, there is something that causes rising market power and slowing dynamism). But in an Aghion-Howitt model, markups and profits are an incentive to enter. You’d expect profits to generate entry.

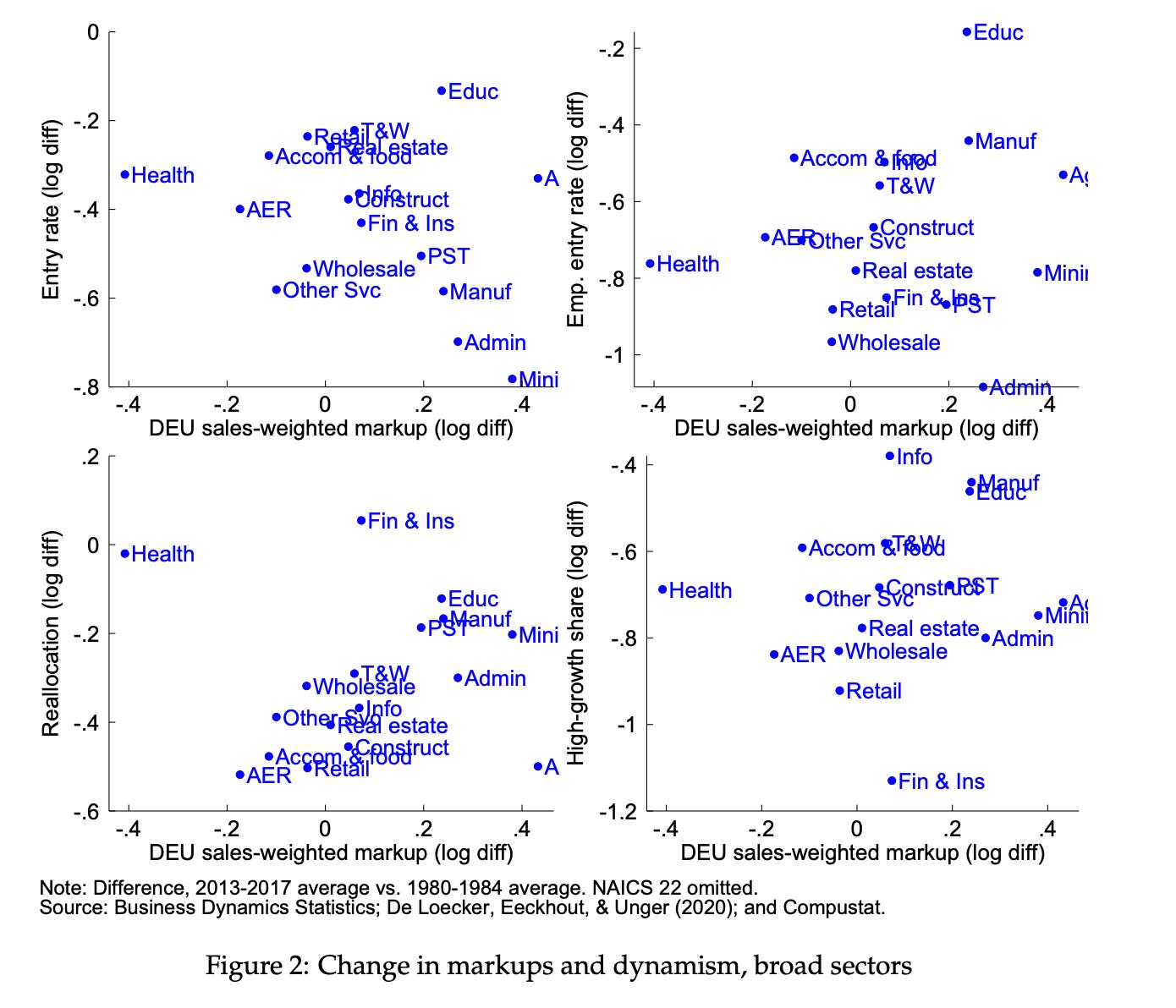

Looking quickly, by industry, at how markups have changed (x axis) and business dynamism changed (y axis), there isn’t a systematic relationship.

This isn’t a direct test of the Aghion-Howitt model, but this is also what we should expect to see in equilibrium. High markups attract entry. Entry erodes markups. In steady state, you get an equilibrium level of markups that balances these forces. At the very least, there is something going on beyond the standard narrative about how the economy is going to hell and it shows up as high markups.

I’m shameless and talking about my own work but this is right in Aghion and Howitt’s work.

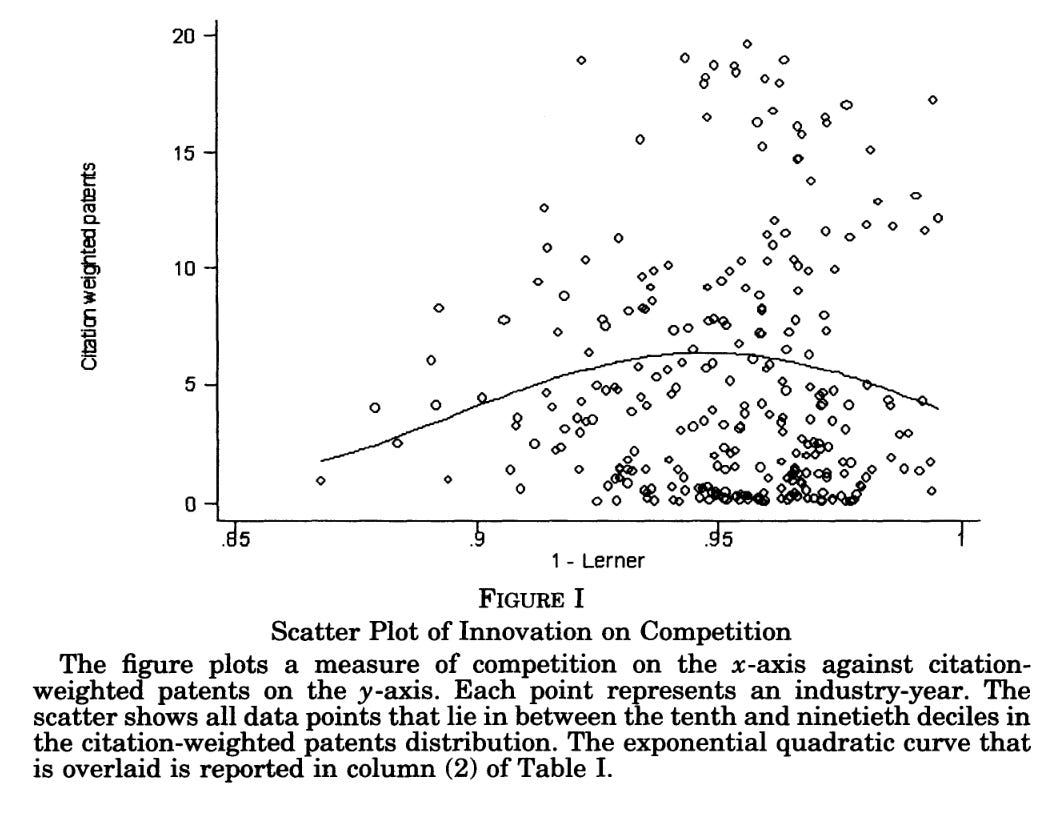

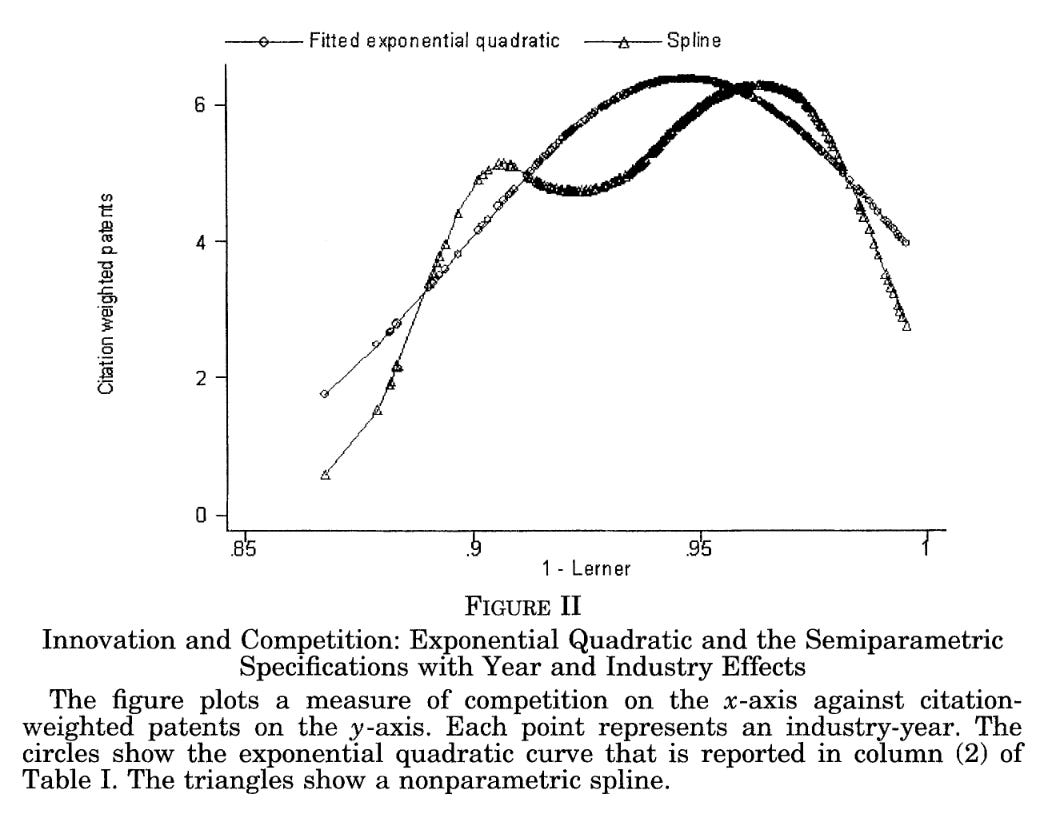

In follow up work, Aghion, Howitt, and co-authors showed the connection between innovation (connected to dynamsim but measured differently) and concentration level (their bad measure of competition) is an inverted U. A protected monopolist has no reason to innovate. Add some competition and firms innovate to escape their rivals—the “escape competition” motive kicks in. But make competition too intense and expected profits from innovation shrink so much that firms stop investing in R&D. Why bother if any breakthrough gets immediately copied? Aghion, Bloom, Blundell, Griffith, and Howitt found exactly this pattern in UK firm-level data.

The empirical relationship remains disputed, though. This is a super controversial topic, much like last year’s Nobel winners’ papers. The important part, and why the Aghion-Howitt model is so well cited, is that their Schumpeterian framework can accommodate these realities. It requires more complex modeling. The fundamental insight (that market structure and innovation incentives are deeply intertwined) remains, even as models evolve to include more complications

Overall, this is just such a great prize. I’m pumped. It recognizes the core question in economics: why sustained growth happened at all. Mokyr showed us the historical prerequisites—the institutional and cultural foundations that made continuous innovation possible. Aghion and Howitt built the analytical framework to understand how that innovation translates into steady growth despite constant upheaval at the firm level. Together, they explain not just that we got rich, but how and why. That’s what a Nobel Prize should reward.

Profit drives innovation. But concentration of power in an industry with vertical and horizontal integration stifles competition and makes profits less because of the higher cost of entry into that market.

You don't need to build a better mousetrap if you control the market.

One part I see missing (or I just did not see it). A better mousetrap is part physical reality and part perception. If you are a master at perception (PR and marketing), you can build a perceived better mousetrap without actually building a physically better mousetrap. And PR can be a lot less expensive than physical innovation.

We and the world have all become masters at PR and saying the right thing (talking points) to create the right perception. I wonder how this affects the model.

Fantastic post! But an even better example of how the Republic of letters would have benefited a scientific genius was Galileo. He was sponsored by a rich duke and made tremendous contributions but ultimately he was unable to spread his obviously innovative ideas because the church persecuted him. Newton in England had no such problems just a few decades later because he was effectively part of that republic of letters where him and Leibniz were able to communicate with other intellectuals in other countries.