And The Real Nobel Goes To...

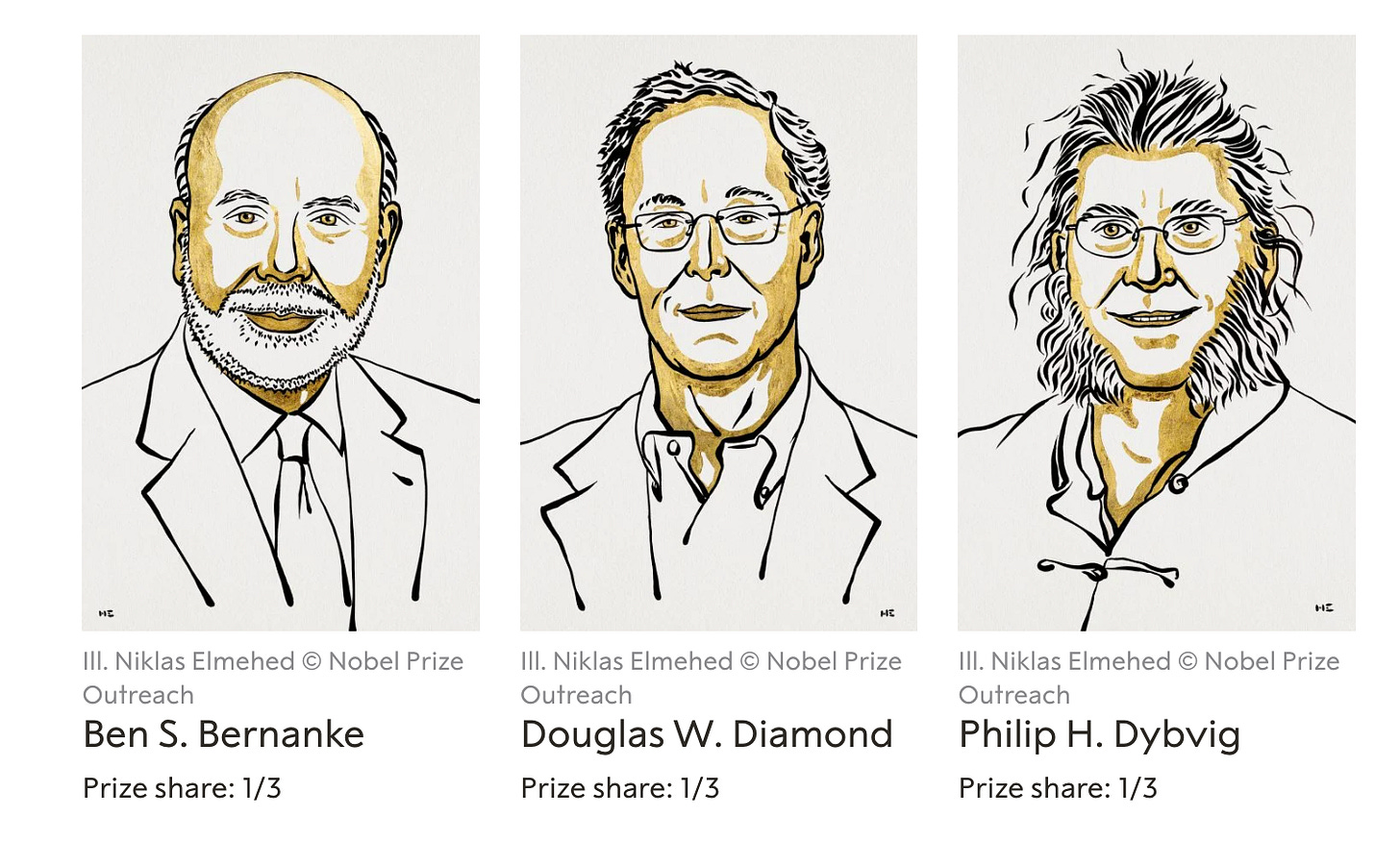

Bernanke, Diamond, and Dybvig “for research on banks and financial crises.”

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. You can support our newsletter by signing up here:

This morning the Economics Nobel Prize was awarded to Ben S. Bernanke, Douglas W. Diamond, Philip H. Dybvig "for research on banks and financial crises."

What does that mean? The Nobel committee has a press release, along with a popular explanation, and a detailed scientific explanation for the prize. Easy, medium, and hard, if you will.

I have a few recommended readings and thoughts for Economic Forces readers. While this prize isn’t bread-and-butter price theory, it is much more closely related to the topics we discuss here than last year’s prize.

All three have been constant favorites to win for years, so this is no surprise. If we were a big newsletter, we could have prepped a release like the what newspapers do when celebrities are expected to die. Alas, it’s just me and Josh so here are some thoughts quickly this morning.

Ben Bernanke

Let's start with Bernanke. He's most famous for being the chair of the Fed during the 2008 Financial Crisis. It's often said that he was the perfect chair at the time since he'd spent his academic career studying the Great Depression and the financial crisis associated with it. I’m not sure how much I agree, but it is said

The classic paper on the Great Depression is Bernanke's 1983 AER "Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression." In it, Bernanke builds on the Friedman and Schwartz study of the Great Depression by focusing on banks. Friedman and Schwartz focus on household balance sheets and especially the supply of money. Always the supply of money with that Friedman guy. Get another hobby! Anyways, I digress. Bernanke adds banks to the story of the depression and that’s why the Nobel is for banks and financial crises.

The key aspect of banking is that the bank is an intermediary between savers and borrowers. They are a business like many others with different quirks (some we will get to with Diamond-Dybvig) but they are a business nevertheless.

When the bank's costs as an intermediary rise, that raises the price of their services. That means it it raises the costs of borrowing and makes credit too expensive for some people. Bernanke argues that mechanism turn a regular downturn in the Great Depression.

While that’s the OG Bernanke paper, he wrote a ton of papers on financial crises and banking. The Nobel committee cites 13 papers directly related to the prize. He’s too cool for a Google Scholar page but here are some others.

If a formal macro model is more your style, Bernanke and Gertler (1989) ties together the borrower balance sheets (related to Friedman and Schwartz’s explanation of the Great Depression, remember) and the costs of intermediation stressed in the 1983 paper above. For something more digestible from Bernanke's academic career, I'd look at his 1995 JEP, again with Gertler, on credit and monetary policy.

But the Great Depression was the main focus of early career Bernanke. He wrote enough papers just on the Great Depression to have a whole book of essays in 2000! That's why many people saw him as "the perfect candidate for the job" in 2008.

Diamond-Dybvig

Let's move on to Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig. Let's start with the pair and their famous model. Economists talk all the time about Diamond-Dybvig like it's an entity. Apparently, the parents gave the kids both names with a hyphen. Bad joke.

Diamond-Dybvig is a model of bank runs. It's often seen as THE model of bank runs. Not many economic models are famous enough to warrant a Wikipedia page. Forget the Nobel. That's how you know it's big.

Again, we think of banks as intermediaries between savers and borrowers. The tension is savers prefer to have money readily available (like a checking account) and borrowers want to make long-term investments.

This isn't a problem if banks know exactly when savers are going to demand their money back. The banks stagger their long-term loans so each period they have cash. But if they don't know, they may not be holding enough cash on hand and not be able to honor their deposits.

But if the bank won’t have their deposit, why would savers make the deposit? One answer is “savers don’t know” but that doesn’t cut it in a rational-expectations world. What Diamond-Dybvig was able to do was to tie these parts together in a simple model.

In their model, there is a good equilibrium where savers and borrowers go about their lives. However, there is also a bad equilibrium. Worrying that the bank may not be holding enough cash, the depositors may "run" on the bank and all demand their cash, even though the bank is solvent. This is a standard bank-run story. Since there are 2 equilibria, "anything that causes [consumers] to anticipate a run will lead to a run." including random events that have nothing to do with the bank's action. The switching between the equilibria. This is meant to capture the sudden and unexpected nature of bank runs.

Of course, "runs" aren't unique to what we usually think of as banks. This is basically what happened when the "stable" crypto TerraUSD collapsed this May, as Josh explained.

People, including Diamond and Dybvig themselves, often use this model to justify deposit insurance to avoid the possibility of runs. That has gotten some pushback. For a clear explanation of the model and policy implications, I'd recommend George Selgin’s two blog posts on the Diamond-Dybvig model. (Part 1, Part 2)

While the Nobel committee cites a few other papers by Dybvig, he really won the prize for this one paper. That puts him in league with people like Michael Spence or Ronald Coase, who won for a specific paper or two.

On the other hand, Douglas Diamond, like Bernanke, has written a ton of different major papers related to banking.

I’m no expert on Diamond’s work overall, but one thing I really like about Diamond's work is the focus on monitoring. People, banks especially, don't simply know who is trustworthy and who will pay back. Information is costly! Monitoring takes real effort. This is the famous Alchian-Demsetz point about the reason firms exist. Someone needs to monitor stuff.

In the Diamond (1984) model, banks have a comparative advantage in monitoring the quality of loans, relative to savers. They can also diversify, so they fill the monitoring role as a middleman. Plus, it opens up quoting Schumpeter, so it has to be good.

Alchian, Undefeated

The Diamond prize, especially for the stuff on monitoring, once again makes me sad Alchian didn't get the prize. This is all in Alchian!!!!! We are Alchian fans here if that’s not clear.

In Alchian’s 1969 paper, people do not always know what the supply and demand will be in a time period. They might not even know if a market will exist. However, certain people, called middlemen, can specialize in collecting such information. That’s what banks do in Diamond’s model. In Alchian’s 1977 paper "Why Money?" Alchian shows how money can help with this monitoring problem. Money is easier to monitor for quality. The fundamental friction is the same as the 1969 paper or the Diamond paper. The solution sometimes differs.

Anyways, not awarding Alchian the prize is not the fault of Bernanke, Diamond, and Dybvig. They are all immensely influential and worthy picks for THE Nobel Prize. Congrats!

For more, check out Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok at MarginalRevolution.com. On Bernanke. On Diamond-Dybvig.

Unbelievable. Three guys, economists, who stood by and let the 2007 mess happen, causing much poverty and misery in the US and elsewhere in the world, get a Nobel-prize ???

Well, many others involved got rewarded too, so why not.