Enjoying learning price theory from Economic Forces? Consider becoming a paid subscriber:

Earlier this week, under the leadership of professional anti-Amazoner Chair Lina Khan, the FTC filed its complaint against Amazon. No, not the complaint about how it’s unfair to take 6 clicks to cancel your Prime membership. That was a few weeks ago. This is the big one. It mostly revolves around sellers needing to use Amazon’s fulfillment to be part of Amazon Prime and lowering reach rankings if products are priced lower on other sites. (This is slowly turning into an antitrust newsletter, and no one wants that.)

Instead of covering the arguments in the complaint, I want to use the complaint as an example of how I use the basics of price theory (and all the things we harp on all the time on Economic Forces) to sort through one of the arguments made by the FTC. Nothing about the use of price theory implies certain policy conclusions about the case. I’m just trying to be transparent, as I’ve done in the past, about how I use price theory and reason about these important questions. Besides self-indulgence, the hope is that the examples help readers do the same.

What is Scale?

One of the aspects that struck me upon reading the complaint was all the mentions of scale: Amazon’s actions “prevent rivals from gaining the scale they need to meaningfully compete,” or block companies from reaching “the scale needed to compete effectively in the relevant markets,” or a crucial feature of this market is that it is difficult “for single-category e-commerce companies to achieve the scale necessary to succeed.” Some of these quotes are from the FTC and some are from Amazon/Bezos. One gets the impression that scale is very important in this market with all the talk about it. That seems plausible.

Scale is interesting in antitrust cases because if firms in this market have huge returns to scale, the efficient outcome may well be one giant firm to harness the increasing returns.

But what exactly does the FTC mean by scale? I was getting confused—I admit it, I easily confuse—in particular because “scale” is often listed along terms like “barriers to entry” and “network effects.”

If I have the technology to reach a large scale, that is not a problem from an antitrust perspective, just like being a monopoly is not illegal, as the complaint makes clear. For scale to be a harm in the antitrust sense, Amazon’s actions must affect other companies’ scale.

What are the most basic features that affect scale?

As with any market, the interaction between companies that are linked across many markets is hugely complex. Going purely off intuition, I have no clue how scale plays into competition across markets and how firms affect each other’s scale.

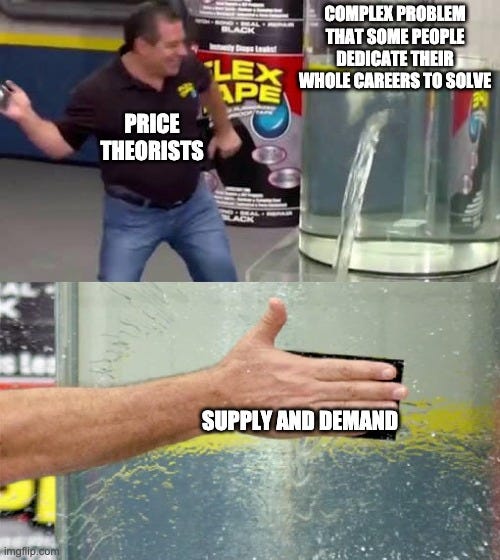

What do I do when confused? Break out supply and demand! To steal a meme from Rafael Jiménez-Durán (HT: James Traina):

Forget all these words about network effects or scale. Supply and demand has quantities. Quantities seem relevant for scale. Let’s start there.

There are two ways for my actions to limit your scale: the demand side or the supply side. That conclusion doesn’t require me to be committed to any of the regular assumptions baked into the supply and demand. The core of supply and demand is that everything falls into one of two buckets: a supply side or a demand side change. Those are the two curves, not a whole lot else you can do.

Now we think through the two sides. What shifts your demand curve? One possibility is that I increase my product quality or lower my price. It’s an effect I’m “imposing” on you that can be seen as a shift of your demand curve. My lowering of prices moves you down your supply curve, which decreases your quantity sold.

You’ve lost customers to me. That sucks for you. Your scale will be smaller. The amount of customers will depend on your elasticity of supply. If there are large returns to scale, when I cut my prices a little bit, I can gain a huge percentage of the market. If there are increasing returns, your costs could even rise. That’s a double-whammy. Your scale is reduced, both in terms of the quantities you sell and the efficiencies you achieve.

But by assumption, none of my actions above generate harm in an antitrust sense. I simply improved my product. It is just a normal part of the competitive process with each firm attempting to outcompete the others. No one could allege otherwise. The FTC certainly is not arguing this is the harm.

Another way that my actions could move your demand curve is that I make your products worse. If I am a phone manufacturer who also owns a browser, I could possibly slow down my competitors’ browsers to make mine look fast. That could be a dumb business decision since consumers would probably blame the phone, but we could imagine businesses throttling competitors. But slowing phones down is really a digression since no one would say that is a scale effect. That can’t be what the FTC means by blocking scale either.

After we’ve exhausted the demand side, the only other place to look is the supply side. Could my actions affect your supply directly? Could I change your costs? Absolutely, in lots of ways.

But we need to be careful!

The first example above where I improved my product is explicitly a demand-side explanation, but it affects the quantity you supply. If you have increasing marginal costs and I make a better product, you will sell fewer products and your costs will be lower.

If you have increasing returns to scale—there’s that scale word again— and a downward-sloping supply curve, improving my products could RAISE your marginal and average costs by improving my products, as shown below.

Both graphs above are what we Econ 101 teachers call a movement ALONG the cost/supply curve. These are NOT supply-side changes, since the supply curve didn’t move. They are also NOT what we mean when talking about “raising rivals costs,” even though in both graphs, my actions raised your observed costs. This also can’t be what the FTC is arguing about scale.

By raising rivals’ costs, we must mean that for any given quantity, your costs are higher. This is a true supply-side effect and what we call a SHIFT of your cost curve.

For example, if I force you to use my shipping but you have a cheaper option, that would increase your costs. It gets complicated in actual cases. If I give you other benefits when you use my shipping, is that forcing you? Compared to a world where you get the benefits but don’t pay for the shipping, that is a harm. But that can’t be the benchmark, otherwise, any time anyone sells me something they are '“harming” me since I would be better off getting the product for free. I’m not here to resolve these issues.

Let’s get back to scale. If I raise your costs that could prevent you from reaching the size you otherwise would with lower costs. Without the size (or scale), you may not even decide to enter if you are no longer able to cover fixed costs. Is that a barrier to entry? It’s certainly making it more difficult to enter profitably, but so would me being so good you can’t compete. This is why it is important to separate out distinct ideas like scale and barriers to entry, even if they are connected.

Raising rivals’ costs is an antitrust harm, regardless of any statement about scale. Scale, while obviously important to the outcomes of online markets, is a red herring for the actual claims about antitrust harms. That is my takeaway from all the talk about scale in the complaint. I see no way around it.

I’m left concluding either 1) scale is reduced because of Amazon quality/prices or 2) scale is harmed but it has nothing to do with scale actually. It can’t be the first. so I must conclude scale seems completely beside the point. Has the FTC confused itself? Seems so.

I could very well be wrong! Scale could be super important to the claims about harm, and I am missing something.

Nevertheless, I think the exercise above is fruitful to work through, because it clarified things for me about the difference between barriers and scale. More importantly, I hope the way I worked through my thinking above made it more transparent for readers to challenge my reasoning. Instead of getting hung up on definitions of network effects or barriers to entry, I’ve tried to put my reasoning in a framework that anyone with Econ 101 training can critique. That’s not everyone in the world, but that’s a hell of a lot more people than can understand the FTC complaint. It’s also more than can understand with the most complicated network model in Econometrica.

In Defense of Overly Simple Models

This wouldn’t be an Economic Forces post without a methodology point about how we use economics. I think it is hugely beneficial to boil arguments down to the simplest possible elements. What mechanisms are at play? What is changing to cause other things to change? From there, we can build up to the more complicated picture. Maybe that complicated picture adds important detail. Maybe it doesn’t. We won’t know until we strip things down as much as possible.

In between “the world is too complex that we can never capture all the subtle details” and “everything is supply and demand,” there is a lot of grey area. Just within macroeconomics, there is a large gap between the most complicated macroeconomic model with 1,000 frictions and 2,000 parameters and the simplest form of aggregate supply and aggregate demand. Economists also have many tools to choose from. The incentives of academic publishing for most economists is to make everything more complicated. There are exceptions; there are huger returns for the Beckers and Lucases of the world to boil everything down to the most basic model. But for most of us who are publishing models in academic papers, complicating is the easier path for generating new results.

Biases in Economic Theory

Jon Steinsson prepared some short remarks for a panel on the future of macroeconomics. As someone who dabbles in macro, I found the whole thing interesting, but as a full-time theorist, I found this line worth mulling over: [Macroeconomics] was very exposed to another problem: models in which markets work well are (usually) easier to solve than models in…

Circling back to the Amazon complaint, I’m not saying that my response captures the full complaint, not even the complaints about scale. It does not. I’m also not saying that every response from commentators should be with such a simple model. They should not. The court should not make a decision based on my newsletter.

All I am saying is that, when possible, simplifying the story as much as possible cuts through a lot of noise. That’s what price theory helps us with. It is something I find useful, and I hope readers will too. We will be less likely to confuse others about the exact mechanisms we are talking about. More importantly, with simple models, we will be less likely to confuse ourselves. And I’m very good at confusing myself, so I need help avoiding that. Hence, I keep going back to supply and demand.

I’ve got a scenario for you that’s a little more complicated than supply and demand curves for a single market, but not much. Suppose I sell my product in two places, on Amazon.com and on my own website, mycompany.com. My supply curve is made up of three parts, production, fulfillment, and advertising. The production part is normal upward sloping and the same no matter where is sell the product. The cost of fulfillment is cheaper if I supply from my own website that using Amazon fulfillment, and the curve shapes are similar. Finally, the cost of advertising per unit sale is probably flat or even downward sloping for Amazon, but for my own website, advertising cost will slope steeply upward, as more and most expense is required to attract additional buyers to my website. I’m not going to spend advertising money to drive people to my website, but even without advertising my website, x% of potential customers are going to look up mycompany.com just to check it out. Since my marginal cost is less for my website, because my fulfillment expenses are lower, I will offer a lower price there. You could say there are two markets, a highly organized market on Amazon.com, and a disorganized market on the Internet outside of Amazon. The equilibrium price will be different in each market, because the supply and demand curves are not the same in each market. Except Amazon is using its market power to keep me from offering a lower price in a market that’s cheaper for me to operate in.

As an analogy, consider a farmer whose farm is 30 miles outside of a city. He sells most of his produce to a grocery chain that sells his produce in the city. He also runs a farm stand on the road by his farm. He has to sell most of his produce to the grocer, because the city is where the customer base is. That huge customer base is what Amazon has achieved with its “scale.” But he makes more profit on produce sold at the farm stand, and he maximizes that profit by charging a lower retail price at the farm stand, which entices some customers to drive out from the city to buy directly. What Amazon has been doing is telling the farm stand that prices have to be the same as in the grocery, or they will put his produce in the back with the light bulbs and expired bananas.

Amazon may complain that if everyone can offer lower prices on mycompany.com than on Amazon.com, people will shop on Amazon and then go to individual merchant sites to actually buy the product. Of course this was part of Amazon’s initial growth strategy, get people to shop at brick and mortar stores before buying for a lower price on Amazon. What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

I don’t disagree with this analysis, but I do think what is simplified to us economists is actually more complex than the intuition some people have about scale. I think how individuals interact in the market more intuitively understands the results of this model you have through the concept of “big business bad” simplifications. The fallacies can be really important to point out there if used in the wrong way (natural monopolies etc.) but I think these legal arguments at this level need to fly in the court of public opinion as much as economics and law. I hope your arguments help frame the latter, but I don’t expect people to frame the former with price theory (even if we like it). :)