Are you paid what you're worth?

Louis Makowski and Joseph Ostroy gave us the tools to think about value

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 12,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Everyone thinks they’re underpaid. Everyone thinks they have to overpay for other stuff.

In policy debates, we see this overpay idea when critics deride certain companies—often larger, often tech-related—as undeservedly "taxing" consumers, workers, or other companies. Outsized profits or charges supposedly demonstrate exploitation from market dominance rather than fair (to whom?) returns.

But this taxation metaphor is argument by wordplay. What is a tax? What constitutes unearned profits versus legitimate competitive payoffs? And how precisely do companies extract surplus compared to value created? Are we stuck with just arbitrary comparisons of what feels like “too high” of a price?

One option is to say all voluntary transactions must be mutually beneficial. Therefore, every return is earned by profiting the other side of the transaction with a net benefit and thus a willingness to trade. We can call this the Argentinian Prime Minister Javier Milei approach. It has merit, grounded in what economists call revealed preference. Unfortunately, it assumes away the hard cases, as I’ll highlight below.

Luckily, the most underappreciated economic theorists of the past 40 years, Louis Makowski and Joseph Ostroy spent their careers developing the formal language for us to answer this question. The key is to ask, what is each person’s marginal product? Are people receiving their marginal product? With these simple questions, applied systematically, we will gain insight into efficiency, innovation (this is the paper I recommend to most new readers), socialism, and even “taxing.”

This week’s newsletter will explain how to use the idea of a marginal product to ask important questions.

Marginal Products

If you’ve ever heard about “marginal products,” I am confident it is in a firm production context. Economists talk about the marginal product of labor. Just a reminder of what that is: consider labor as an input into making computers. The marginal product of labor represents how total output changes per extra unit of labor. If a firm hires one more worker or the workers work one more hour (whatever unit you use), how much does total output change? That is the marginal product of labor. You can do the same thing with some form of capital. If you use one more robot, how much does output change? That is the marginal product of the robot. Roughly, in competitive markets, workers receive pay equal to the market value of their marginal product.1

But conceptually, one can also define the marginal product of many things. We can define the marginal product of a particular worker. That is essentially the same as the marginal product of labor.

We can go one step further, and ask, what is the marginal product of this person overall, not just as a worker? This becomes much more abstract, but the idea is the same.

As before, we want a way to think about the world with and without that person. First, see what the world is like, as is. Compute economy-wide production with that person present. Next, imagine they didn't exist. How much would output decline? How much worse off is everyone in the economy? The total output decline quantifies their incremental contribution. This is the “marginal product of a person.” For simplicity, we can imagine this is a dollar amount. If you don’t like adding utilities and output, that’s a separate issue we can discuss later.

Again, a competitive environment would reward every individual with their marginal product. Think pro sports stars. Assess fan engagement and revenue with LeBron James in the NBA this year versus without him. His mammoth salary captures much of that incremental value. Do this exercise across all possible things LeBron does (NBA, shoe companies, and even personal relationships), and you have his total marginal product. If his total pay equals his total value added to society, we have a competitive economy overall for that person. If this is true for all people, the market is competitive.

This framing easily connects competitive markets to efficiency. Why are competitive markets efficient? It is always true that each person has an incentive to make their part of the pie as big as possible. In a competitive market, each individual "fully appropriates" her contribution to society, in the terminology of Makowski and Ostroy. If each person fully gains what she contributes, there are no externalities and each person making her personal pie as big as possible makes the overall pie as big as possible.

The logic of marginal products and full appropriation extends to firms. Let us take the usual short cut and think of the firm as a single entity that makes decisions. What is the firm’s marginal product? Again, we imagine the firm does not exist. How much worse off are all of its owners, workers, customers, suppliers, etc?

In contrast to what your textbook misled you with, in a competitive market, it is not true that each firm earns zero profits. Instead, each firm’s profit is its marginal product. If there are a bunch of companies that can do the same thing, this firm is adding nothing unique, so its marginal product is zero. If it disappeared, an identical firm would fill the void. The key assumption behind zero profits is that technology can be replicated by anyone who wants so firms are essentially replicable and each one adds nothing special. This is the reason the baseline Bertrand competition is competitive, even though there are only two firms and each sets its own price.

Reader Questions: On Price-Taking and Competition

We will switch things up today and answer some questions that I received from an astute reader, Ashwin Varma. Ashwin is a medical student, and I’m pumped to have non-economists, not just reading Economic Forces but also seriously engaging with the ideas. Thanks, Ashwin!

But if it is an innovative or more productive company, it will earn a profit in a competitive market.

Are firms overpaid or underpaid?

That’s all nice for considering the knife-edge case of perfectly competitive markets. But what about other markets? How does this help us determine if Apple is earning some unjustified “tax” or not?

We can use the same framework of comparing the firm’s marginal product to its profit. Does its profit match, exceed, or fall short of its marginal contribution to society? Or, in other words, does it fully, under-, or overappropriate its marginal product? Does it overappropriate?

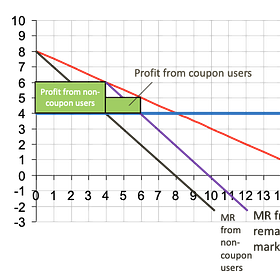

As I’ve argued before, in the baseline model beyond perfect competition, instead of imposing some unwarranted tax, the firm underappropriates its contribution to society. It generates a net positive externality and thus undersupplies its products relative to a competitive, efficient market. Read the piece before for that whole explanation.

Monopolies don't make enough money

Building on last week's theme, thanks Josh, I want us to think about counterfactuals today—that dreaded, "compared to what?" we economists harp on. Instead of focusing on the first model taught in undergrad, I want to jump all the way to the second model: monopoly. 🤯

That doesn’t have to be true. If I’m a monopolist because the government or I threaten anyone who enters, it is likely that I am being overpaid for my services. If I disappeared, someone else could do my exact same job and so I was contributing nothing.

Unfortunately, or fortunately, most of the interesting questions are grey areas where it is not immediately clear.

Take pharmaceutical patents. There is a worry that without the patent, innovation will be greatly diminished, since the idea will be copied and the person who contributed the idea will not reap the benefits. Take something like the Covid mRNA vaccines. They generated huge social benefits and so the companies were underpaid. But the patents help bring their profits more inline with social benefits.

But that’s not always the case. If I patent something that you would have come up with independently the next day, my contribution is very small. However, a 20 year patent allows me to keep you out of the market and earn a profit in excess of my tiny contribution.

Antitrust cases can be studied in a similar way. The company is taking some action that keeps out competitors. If the way they keep out competitors is by simply being the best product, they may earn huge profits and have high market power, but they are likely underpaid. That is the monopoly case above.

That is different from keeping out competitors by some other means. While not literal force, maybe there is a grey area where the company’s actions are like the patent example: they keep out competitors without contributing anything. Each case is going to be different, but we have a framework for thinking through the problem.

We can now move onto the notion of a “tax” by a company. The most reasonable interpretation of what people mean when they say tax is the ability of a company to overappropriate, relative to its value added or social contribution. In that case, the company is a negative externality on other people. (I’m not sure what that says about government taxes but we will leave that for another newsletter.)

Now, compare the economy with and without a company like Apple. Total surplus falls sans iPhones and MacBooks. App developers lose money. Consumers are worse off. That’s obvious. Does Apple's profit currently capture that lost consumer and producer value? If yes, incentives look apt to maximize societal gains. If not, which direction is the mismatch? Is Apple able to overappropriate its contribution? If Apple disappeared, would a similar company take its place and so Apple is doing nothing special?

I don’t have an answer.

But thinking in terms of marginal product provides a systematic, useful perspective for understanding competitive forces and how earnings get distributed. In an ideal competitive market, the extra value that a company or worker contributes to total economic production would equal what they personally receive in profit or pay. Their private marginal product would match the social marginal product.

When we think we observe gaps between private versus total value added, it signals obstacles blocking fuller contributions and payoffs. Which way is the force? Companies may face constraints keeping them from expanding output to efficient levels that competition would unlock. We want to find ways to increase that companies reward. Workers may confront barriers like occupational licensing or non-competes dulling effort below their potential. Policy can change that. But it could easily go the other way and these policies do a good job of aligning incentives.

Again, this is highly sensitive to the particular case in mind. As with much of economics, the goal is not convince you of an answer but of providing a toolkit for asking questions.

Technically, in competitive markets, workers would be paid the value of their marginal product if they go and work for their next most productive employer. It requires the assumption of two equally productive employers to get the usual “workers are paid their marginal product” result.

You mentioned LeBron, which got me thinking about payments under constraints. Superstars like LeBron are subject to max contracts, suggesting that they are underpaid. Rookies are subject to fixed contracts based on draft order. They are generally underpaid because they can't vote in the union until they sign their contract. That leaves veteran non-max players whose comp. Is the remainder of the 50% of revenue paid to players under the CBA. They would appear to be overpaid relative to others, although the 50% may undervalue the marginal product of the players as a whole as collectively they are close to monopolistic since they are the best roughly 500 players in the world. Your thoughts?