I’ve taught thousands of economics students the introductory model of tariffs: a tariff on washing machines raises their price, harming households, but benefiting U.S. manufacturers. The households’ loss is larger, so the tariff ends up destroying wealth for the country. This conclusion makes economists unpopular with many politicians.

Recent research has convinced me that the Econ 101 story is generally too simple to apply in a modern economy. Pro-tariff politicians are right about that. But they have the direction wrong: tariffs are even worse than the textbook model suggests.

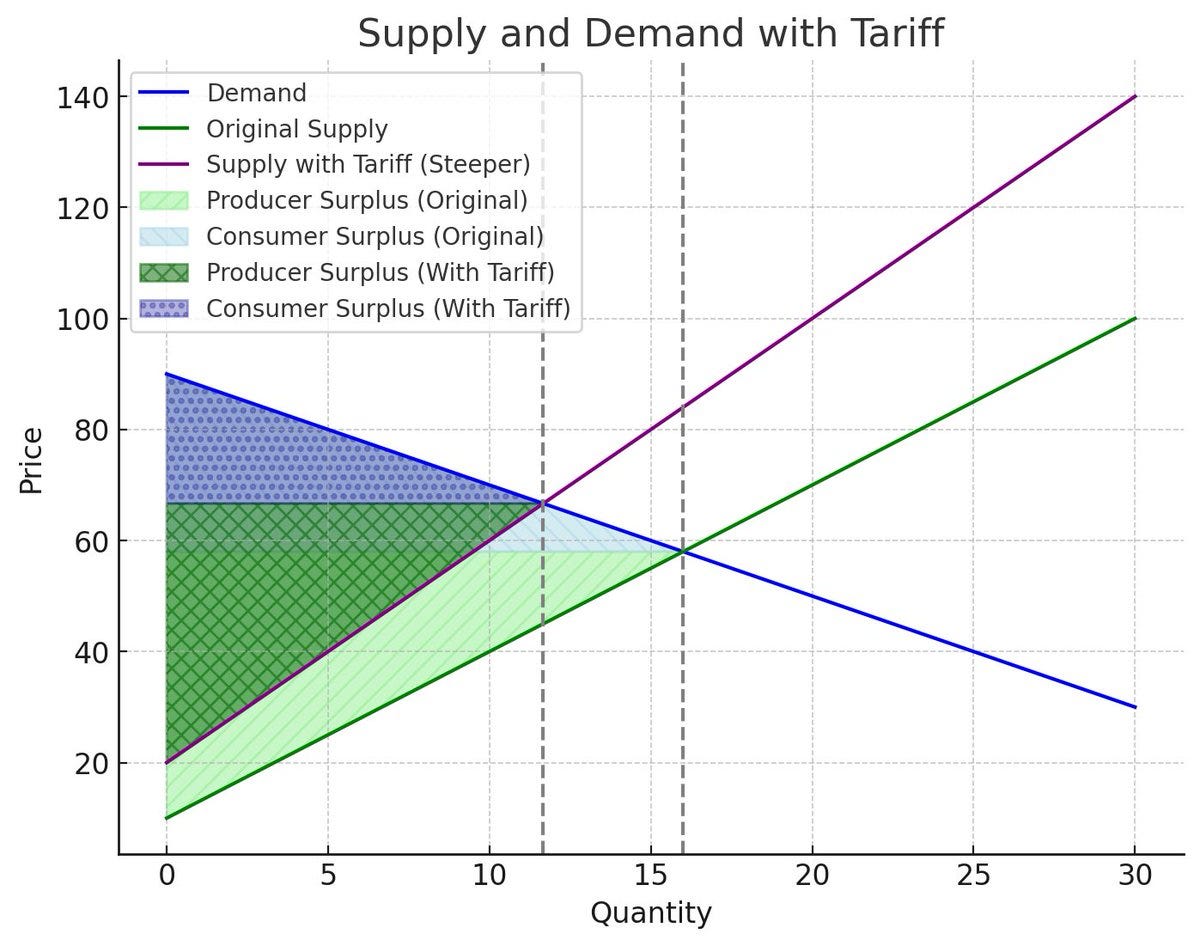

It’s usually not the main takeaway, but there is an upside to tariffs in the basic model; tariffs benefit domestic manufacturers. The standard trade model taught in Econ 101 is shown below. It’s supply and demand, but where the usual sloped curves are only the domestic supply and demand. On to that, we add a world supply curve that is horizontal at the price P_world. With the tariff, the price is bumped up to P_tariff.

By shielding domestic producers from foreign competition, tariffs allow these producers to charge higher prices and give them a new opportunity to expand production. The yellow region of producer surplus grows. That’s why companies facing import competition will lobby for trade barriers. For some people (and this is a normative argument, not a positive economic argument), the benefit to domestic producers and their employees is worth more than the harm to consumers; there’s a redistributive reason for the tariff.

Tariffs are a tax on intermediate goods that manufacturers use

As I’ve explained before, one implicit assumption in this argument is that trade is in finished products for consumers. But a large part of international trade occurs in intermediate inputs and components, not finished products ready for consumers. Companies import parts, materials, and unfinished goods to use in their own production processes. This means tariffs often act more like a tax on domestic manufacturers who use these imports, raising their costs instead of protecting them from foreign competition. If the neat separation between consumers and producers ever existed, it doesn’t today.

Apple designs iPhones in California but contracts manufacturing to hundreds of suppliers peppered across Asia. Is this domestic or foreign production? Tariffs on these imports directly affect a major U.S. producer. The clean divide between domestic and foreign firms doesn’t reflect reality.

In fact, a big part of international trade occurs within multinational corporations, not between independent buyers and sellers. Roughly half of U.S. imports and nearly a third of exports are between “related parties.” Any tariff on this trade is paid directly by U.S. companies.

We learned these lessons about the modern economy not from the “common sense” that J.D. Vance appealed to in his vice presidential debate, but through careful data collection and analysis from economists—often economists with PhDs. Their detailed research reveals how these cost increases ripple through supply chains and ultimately harm U.S. exports.

For example, research by Handley, Kamal, and Monarch examining the 2018-2019 U.S. tariffs—which included duties on solar panels, washing machines, steel, aluminum, and a wide range of Chinese imports—found that products more exposed to tariffs on imported inputs experienced significantly lower export growth. This effect was equivalent to foreign countries imposing a two percent tariff on U.S. exports. On average, exports of unaffected products grew two percentage points faster than affected items. The tariffs intended to protect domestic industries ended up acting as a tax on U.S. exporters, undermining their global competitiveness. That is the opposite of protecting American jobs.

The Econ 101 model misses another crucial aspect of real-world tariffs: the other country often retaliates with tariffs of its own. This harms domestic exporters, potentially wiping out any gains for import-competing industries. When the United States imposed tariffs on over $400 billion of Chinese goods in 2018-2019, China retaliated, notably with tariffs against U.S. agricultural exports.

The net effect is fewer manufacturing jobs

Given these complications, what actually happens when countries impose major tariffs? The same wave of U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods provides a clear example. Instead of helping U.S. manufacturers, Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce found that these tariffs led to higher costs for manufacturers using Chinese inputs, job losses in industries reliant on Chinese imports, only small employment gains in protected industries, and higher consumer prices across many sectors. Overall, the negative effects of higher input costs and reduced exports outweighed any benefits from import protection for manufacturers as a group.

As we dig even deeper, the problems with tariffs keep piling up. The uncertainty that accompanies the threat of tariffs, even before implementation, can chill business investment. Companies delay decisions on new facilities or supply chains when trade policy is in flux. During the U.S.-China trade tensions, many firms reported putting investment plans on hold because of uncertainty over tariffs and retaliation. This dampens economic growth beyond the direct impact of tariffs.

Consumers are also hurt in ways less obvious than higher prices. For example, tariffs also reduce their options when they shop. Go into any grocery store today at any point of the year, and you will see a dozen kinds of fresh fruit. How? Modern trade. Consumers benefit from this variety instead of being stuck with canned peaches all winter. Amiti, Redding, and Weinstein find variety accounts for half of the trade-induced GDP growth. Trump’s tariffs reduced the varieties of the affected goods. There's no reason not to expect the same from future tariffs.

In the end, critics are right that the simple model misses many details, and the effects of tariffs are more nuanced than simple price increases. But politicians and their friends who use this complexity to justify protectionist policies are drawing exactly the wrong conclusion. The detailed research shows that, in a world of global supply chains and multinational production, major tariffs are likely to be far more damaging—especially to manufacturing jobs—than even basic economics would suggest.

Agree, thank you. I own a home textile factory in the U.S. where we cut, sew, stuff fabric into pillows etc. Fabric import tariffs have been hurtful to our business especially as foreign manufacturers are able to ship finished products direct to consumer tariff-free under the de minimis exemption. We provide well paying jobs with benefits so this hurts U.S. workers. All of that is to say, you have captured the other layer of complexity here in an already globalized world.

I am asking myself to what degree multinational corporations could decrease their tariff burden by reporting artificially low prices for input goods before they import them along their supply chain to the U.S. If multinationals could do this and SMEs couldn't, then tariffs would again go in the opposite direction as intended by pro-tariff politicians.