In Defense of Price Theory

Sometimes it is the process that is important

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 13,500 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Recently, there has been a great deal of debate about the value of price theory. (We’ve apparently come a long way since the creation of Economic Forces!) Much of the discussion has centered around a recent op-ed by Steven Landsburg lamenting that students aren’t learning price theory (something for which we are very sympathetic!). In motivating his discussion, Landsburg describes an exam question that he gives his students:

Here’s an economics brain teaser: Apples are provided by a competitive industry. Pears are provided by a monopolist. Coincidentally, they sell at the same price. You’re hungry and would be equally happy with an apple or a pear. If you care about conserving societal resources, which should you buy?

…In a competitive industry, prices are a pretty good indicator of resource costs. Under a monopoly, prices usually reflect a substantial markup. So a $1 apple sold by a competitor probably requires almost a dollar’s worth of resources to produce. A $1 pear sold by a monopolist is more likely to require, say, 80 cents worth of resources. To minimize resource consumption, you should buy the pear.

Much of the initial reaction to his op-ed and this example was positive. People correctly pointed out that the usefulness of the example is that it gets students to think about marginal cost and opportunity cost is an unconventional way. Also, students are likely to remember the question and its answer because it seems counterintuitive.

However, it didn’t take long before critics starting attacking this example. The initial attacks seemed to be about the example itself, but that quickly morphed into a criticism of price theory overall.

Critics suggested that the question and the answer that Landsburg provided actually ignored a number of other factors. Many raised questions about the use of the monopolist’s profit. For example, suppose that 20 cent profit per pear was spent on purchasing tires and setting them on fire. Would that really be good for conservation and the environment? While there is actually substance in that claim, some critics then sought to attack Landsburg himself for not being quite as clever as he thinks. They also attacked price theory for being a useless tool since its answers rely more on one’s knowledge of the cleverness of the economist who wrote the question than knowledge of economics.

Even setting aside some of the bad faith arguments, readers will not be surprised to learn that I think that the critics have entirely missed the point. In particular, I think that (a) price theorists take a much different approach to exam questions than for research questions, and (b) they are correct to do so. Allow me to elaborate.

Price theory is fundamentally just a set of tools for thinking about the world. Brian and I have written about that before. One important characteristic of the price theoretic approach to teaching is the use of open-ended exam questions. No doubt some readers have seen old copies of University of Chicago price theory exams, which are filled with True/False/Uncertain questions. The value in asking questions of this sort is that one often doesn’t care so much about whether the student says “True”, “False”, or “Uncertain”, but rather how they justify that answer.

I give questions like this all the time. In fact, if I assigned Landsburg’s question, I would have written it as:

Apples are provided by a competitive industry. Pears are provided by a monopolist. Coincidentally, they sell at the same price. You’re hungry and would be equally happy with an apple or a pear. State whether the following is True, False, or Uncertain and justify your answer. If you care about conserving societal resources, you should buy the apple.

By framing the question in this way, people can answer however they like and many of the good faith critics of Landsburg would have provided acceptable answers, even those answers were distinct from his preferred answer. In other words, what is key is whether the student provides a compelling and correct application of price theory in response to the question.

Perhaps a different way of saying this is that, over time, exams seem to have become more and more focused on getting the correct answer in the sense that there is only one correct answer. This certainly makes exams easier to grade! However, it often comes at the cost of determining what the student has actually learned or whether they know how to apply what they have learned.

To give an example of what I mean, I would like to refer to a great source of exam questions for price theory courses, Robert Frank’s The Economic Naturalist. That book grew out of an assignment that he would give his students. They were expected to pose a question about something they observed in their life and answer those questions using economic reasoning. The main point of the assignment was to use economic reasoning to answer interesting questions that arose in their daily life. The book includes some of the best questions (and answers) that were submitted for his class. It also includes some of his own questions as well as questions posed by other economists. Examples of some of the questions from the book are as follows.

Why does a new car that costs $20,000 rent for $40 per day, but a tuxedo that costs $500 rents for $90 per day?

Why is milk sold in rectangular cartons, while soft drinks are sold in round containers?

Why do so many restaurants offer free refills on beverages?

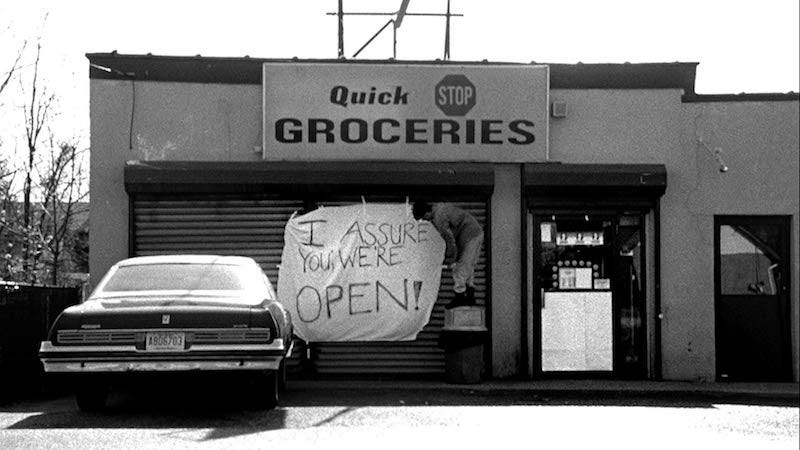

Why do 24-hour convenience stores have locks on their doors?

If all you are interested in doing while teaching a course is checking to see if a student has the “correct” answer, then asking questions like these is a really bad idea. In an introductory class, you are likely to get the same number of distinct answers as the number of students in the class. And yet, I would argue that this is precisely how students learn to understand price theory and that these are the sort of questions you want to give them. Each of these questions forces the student to think about supply and demand, costs, what consumers value, and what they are willing to pay.

For example, take the 24-hour convenience store example. If you pose this on an exam, a frequent answer is that although such stores are open all day, every day, locks do provide some option value. The store owner would like to be able to lock the doors in particular instances, such as when they shut down for emergencies. The lock is likely a pretty small cost relative to the value of being able to lock your doors if needed for the duration of the life of the door. Other students might answer that the company that makes these industrial doors might find it more expensive to make two different types of doors, especially since the demand for doors without locks is likely to be small relative to the demand for doors with locks. Since one always has the option not to use a lock, companies might simply specialize in doors with locks to minimize costs without any real loss to those in the market who don’t need a lock.

In my class, both answers would be acceptable if this question was on my exam.

Another fun question is to ask why food costs so much more in a restaurant than for the raw materials themselves. An obvious answer is to say that you are consuming a bundle. You are not only getting the food, plus also a service. Someone is preparing the food. Someone is delivering it to your table. That adds to the cost.

Earl Thompson’s argument was that the markup of restaurant food over the raw materials was explained by the cost of time. This includes the time cost of your server and the time cost of the cook. The opportunity cost of their time requires compensation that we call wages. But there is also an additional time cost: the time you are sitting at your table. As long as you sit at your table, no other diner can use it. Thus, some of the markup is rent for the table.

But herein lies the crux of the issue. If one is doing economic research, one would actually need to provide a lot of support for any of these suggested answers to the posed questions in order to convince others that they have adequately explained this observed outcome. If one wanted to test Earl Thompson’s insight, for example, they might estimate whether the markup over raw materials for restaurant meals was explained by how long it takes the typical customer to eat the meal.

There is no such requirement on an exam. The purpose of an exam is to measure the quality of the economic reasoning, not whether the answer is “correct” or “wrong.” Thompson’s economic reasoning is sound. Whether it is “correct” is an empirical question.

Nonetheless, even as it pertains to research, price theory provides a systematic way of thinking in order to formulate a hypothesis. One is able to take a potentially puzzling observation and use the tools of price theory to formulate hypotheses that can be tested.

Since price theory is really just a way of thinking, price theoretic training requires coming up with possible explanations for these puzzling questions using the tools that you have learned. Developing and effectively employing that price theoretic approach requires a lot of learning-by-doing in the sense that one must continue to wrestle with these puzzling questions and be interested in what others have to say about them. This exercise is useful for both the student and the teacher. Students are going to develop a much better understanding of price theory by dealing with real world puzzles that don’t have an obvious answer than they will on multiple choice exams. Those who are teaching price theory benefit from having to evaluate new arguments (some bad, some okay, and some better than what they were looking for). That muscle is worth training. And I would argue that exercising that muscle is what creates better economists.

By the way, I left 3 of the questions from Frank’s book completely unanswered. Feel free to leave your suggested answers to the questions in the comments.

When I read price theory analysis, I don’t see a clear distinction from standard economics. There is often some extra detail that looks like Industrial Organization theory.

Would you be so kind to share some resources to teach price theory at undergrad level?