You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Policy today, not politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of 12,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Former President Trump recently proposed a new set of sweeping tariffs to boost US manufacturing and fulfill campaign promises to get tough on trade. I’ve seen various numbers, but all are large and would apply to many goods. Let’s stick with the idea of “federal tariffs on Chinese imports of more than 40 percent” from Jeff Stein.

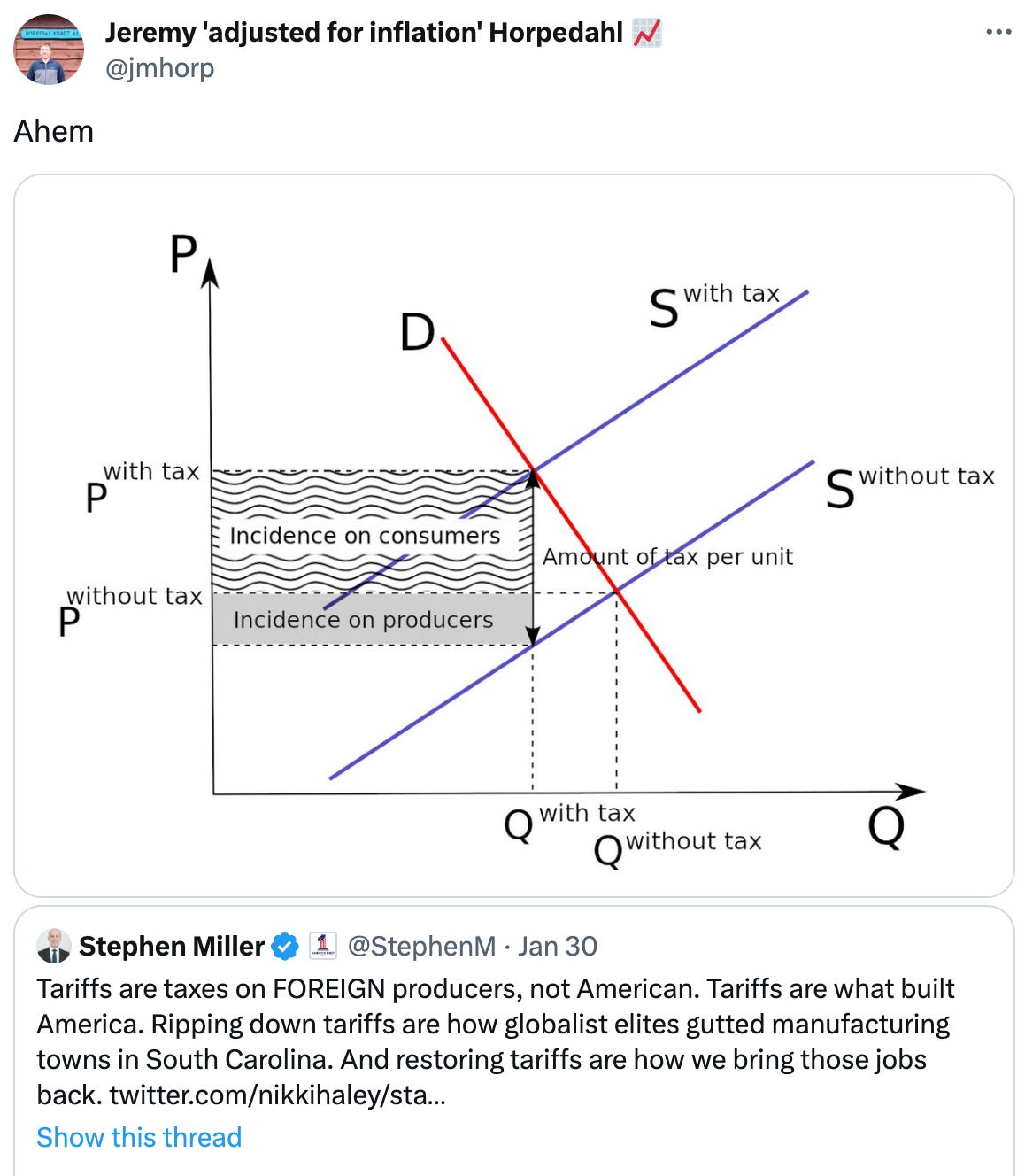

One former advisor to Trump said on Twitter, “Tariffs are taxes on FOREIGN producers, not American.” This led to an absolute roasting by economists across the political spectrum. My favorite response was from Michael Strain: “Sales taxes are taxes on GROCERY STORES, not on the customers buying groceries in grocery stores.” The grocery store comparison perfectly explains why the advisor was wrong.

Literally, the first thing we teach about taxes is the difference between the statutory incidence (who pays the money to the government) and the economic incidence (who bears the burden). Even if foreign producers write the check, the economic costs get passed on via higher prices that fall on domestic consumers and companies dependent on imports. This textbook case of misleading use of statutory incidence reveals how underrated Econ 101 insights are.

Jeremy Horpedahl was there with the graph. A tariff is a tax. It raises the marginal cost of producing a good, which raises the price. Consumers pay a high price (P with tax) and producers receive a lower price. The burden is on both sides of the market.

Let me be the first to say it’s amazing to see all economists rally in opposition to this claim and to the defense of basic economics.

The Econ 101 Trade Model

But is it all just Econ 101? Yes. And no. Supply and demand is still the best game in town. However, applying the basic models is more complicated than most Econ 101 courses make it out to be.

For example, Trump’s former advisor concluded, “Restoring tariffs (sic) is how we bring [manufacturing] jobs back.” Many economists will recoil at this claim. It’s likely not a great idea. But it doesn’t directly contradict basic economics. In fact, a first attempt at applying the Econ 101 model would lead you to that conclusion.

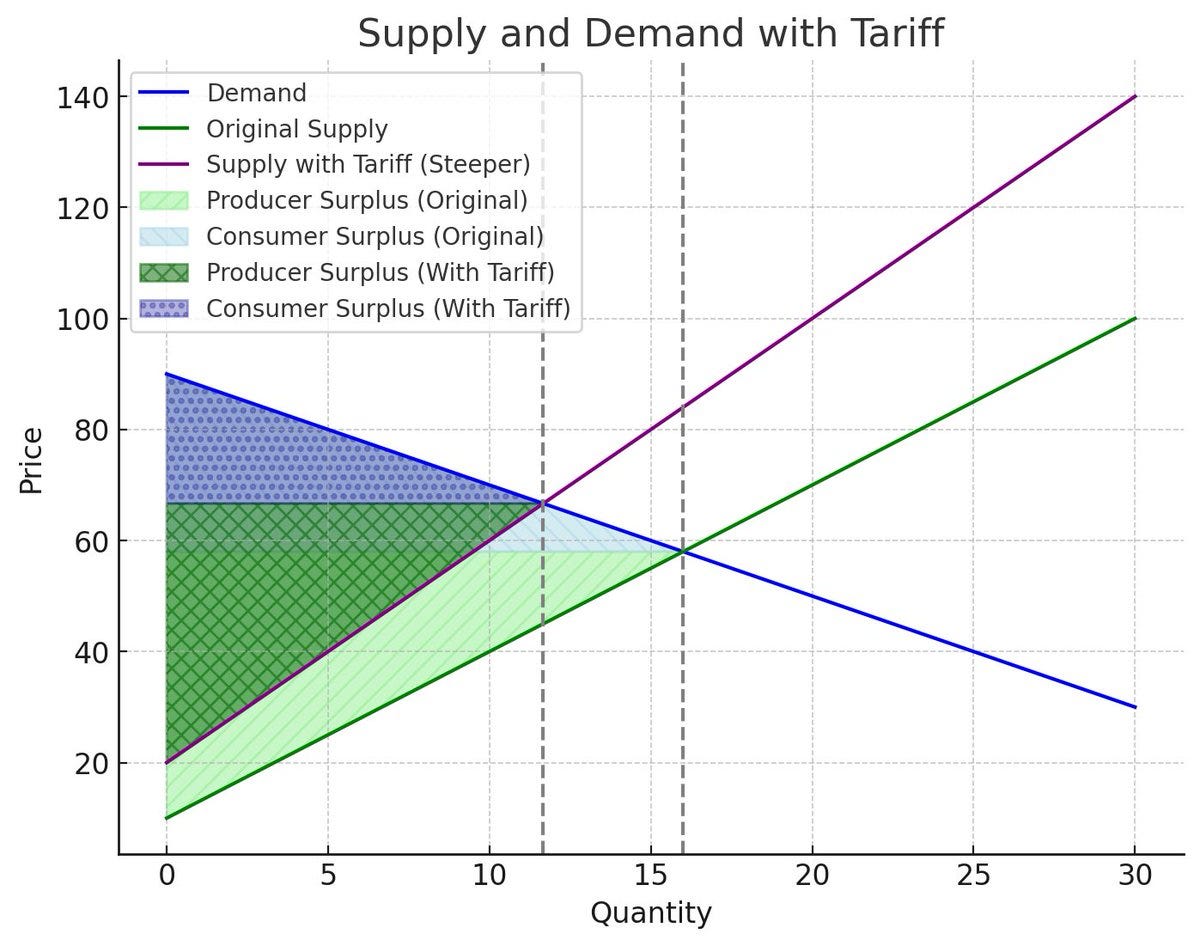

Econ 101 supply-demand diagrams demonstrate an alluring logic for import protections to benefit domestic substitutes. By taxing foreign competitors, trade barriers shift the global supply upward, this raises prices thereby allowing domestic firms to expand output and hire more workers without competition limiting upside. Superficially, such analysis supports tariffs salvaging industries from relentless globalization pressures through guaranteed preferential market access.

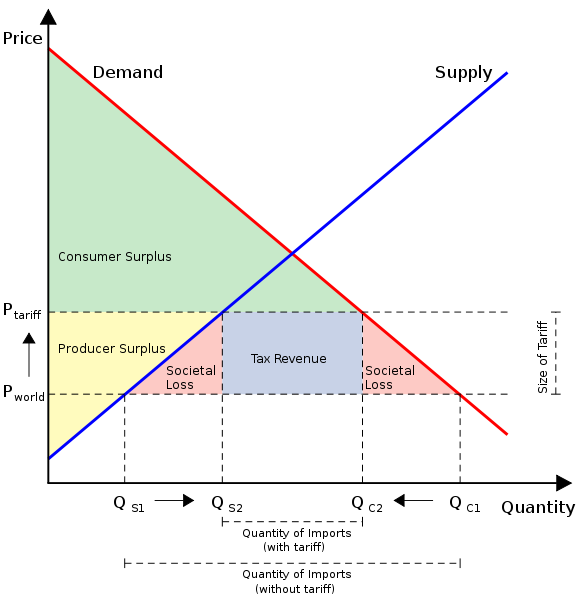

In Econ 101, we often use words and graphs. The standard trade model taught in Econ 101 is shown visually below. It’s supply and demand, but where supply and demand are domestic. In addition, there is a world supply curve that is horizontal at the price P_world. With the tariff, the price is bumped up to P_tariff.

While people may use this model to argue against tariffs—the tariffs lower total surplus—the model does show an increase in producer surplus. The quantity produced domestically increases from Q_s1 to Q_s2, likely increasing employment in this industry (ignoring spillovers or general equilibrium effects).

However, even in an undergraduate course, caveats quickly emerge. Taxing imported final goods suffers deadweight efficiency losses as higher consumer prices suppress consumption below optimal levels. And foreign retaliation can undermine export competitiveness neutralizing domestic gains. Still, the partial equilibrium perspective suggests targeted import protections may engineer favorable, albeit likely temporary, impacts for symbolically shielded sectors.

The nature of modern trade

Yes, we need to know the basic theory. But we also need to know how to apply those theories. What if there are retaliatory tariffs, and the policy starts a trade war? Does trade look like the Econ 101 model?

For example, a huge percentage of trade occurs within firms. US corporations shuffle inputs and outputs across borders within the firm rather than arms-length market transactions. It varies over time, but estimates suggest intrafirm trade comprises 30-50% of all US imports and exports. In 2021, “related-party trade” (another term you’ll see) accounted for 41.3 percent of total goods trade.

As an example of this, one complication I find fascinating regarding trade is the idea of “factoryless manufacturers.” Take Apple. They design and market devices. Apple performs no tangible production. The physical manufacturing occurs offshore at Apple's behest via contracted partner firms concentrated in China. Surely, adding a tariff to these products will affect a company like Apple and its employment. There isn’t this clean divide. In fact, Ding, Fort, Redding, and Schott (2022) find that manufacturing firms “for 16 to 32 percent of the rise in aggregate US non-manufacturing employment between 1977 and 2019.”

A key limitation of the Econ 101 model is that it ignores intermediate input trade across borders. Modern supply chains transit multiple countries with components and materials combined to manufacture final items. In reality, a lot of international trade is less about Americans buying things from foreigners than it is about firms with large American presence optimizing their production processes to best serve American households. The Econ 101 model above is implicitly a model of final goods. Suppliers ship the apples right to consumers’ houses.

In today’s world, firms are often the demand side of the market, the “consumers.” Consequently, import restrictions often tax domestic firms reliant on foreign inputs rather than purely final foreign products. And tariffs can have counterintuitive effects for producers who are both domestic “demanders” in upstream intermediate good markets and domestic “suppliers” in downstream final good markets.

Taking input and output seriously can get complicated. The easiest way to show this is to think of a tariff as raising the costs of the firm that imports. This leads to a reduction of domestic output, not in the tariff industry but in the industry that purchases the goods with a tariff. In this market, consumer and producer surplus goes down as well. Everyone in this market is a loser.

What do we know?

With intricate forces operating in opposing directions, can we gauge the net effect?

Thankfully, yes. Again, economists are there to help. For example, Federal Reserve economists Aaron Flaaen and Justin Pierce empirically analyze the 2018-2019 tariffs covering over $400 billion of Chinese imports. They decompose the tariff effects into: 1) import protection, 2) foreign retaliation, and 3) rising input costs. The first fits the Econ 101 view; the second, trade war effects; and the third, firms demanding intermediate inputs. They then ask how each channel impacted American manufacturing employment, productivity, and prices.

The results largely support longstanding fears over import restrictions. While beneficial import protection shielded some manufacturing sub-industries, these positive effects proved relatively small and were dominated by negative forces. Facing higher input costs and diminished export demand (remember the US exports goods, too), more exposed industries exhibited relative employment declines. And counties more exposed to rising input costs witnessed relative unemployment increases. Higher price received by the producers also confirmed pass-through of higher expenses.

The main figure is below. The estimate the marginal effect of each component holding the others fixed. It is a way of asking, what would have happened if only input costs rise as we saw? For example, higher exposure to rising input costs associates with a 2% relative decline in employment by late 2018. Notice the decimal in the middle figure. The scale of the gains from import protection are small relative to the two other channels.

Maybe surprisingly, despite sizable labor impacts, differential output responses did not emerge. However, the researchers provide evidence that persistent backlogs of unfilled orders temporarily stabilized production levels and prevented declines. This fits intuitions around lumpy adjustment processes, given capital intensity and contract rigidities. Again, these are further complications of the Econ 101 model, not a contradiction of it. There are ways to further complicate things, which may not fit naturally into the model. I’ve been noticeably silent about the trade war aspect. I don’t know how to model the probability of that. If you think infant industries are a thing, that’s not obviously the Econ 101 model.

Applying Economics Artfully

While an important policy question, I’m more interested in the topic for what it tells us about applying price theory. What lessons should economists take from this about modeling the modern economy? The study's findings reaffirm basic economics. Sure, it shows gaps in applying the textbook models, but standard models mostly work when applied using insights from plain, regular, mainstream economics.

The core challenge is pragmatically tweaking simple models to explain new realities. That’s what all the great economists do. It’s not like Armen Alchian drew a demand and supply curve and then headed home. While we always value simplicity for insight, real situations involve complexity. Useful simplification means keeping key details revealing why things happen.

Economic theory is a useful simplification, not literal truth. Suitably basic models reveal counterintuitive outcomes and determine when predictions apply. Modeling is thus creative arts, not robotic science. Trade policy and otherwise requires weighing simplifications versus visible intricacy. There are no one-size-fits all solutions absent judgments on appropriate priorities across dimensions.

So after all those complications, are 40% tariffs a good idea? God no.