Monopsony isn't Monopoly Flipped-Upside Down

We need to be careful when jumping between the two

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. You can support our newsletter by signing up here:

(This week’s newsletter is a slightly edited version of a post that originally appeared on Truth on the Market, a website full of scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more. Check it out, especially this recent symposium on the future of antitrust.)

Slow wage growth and rising inequality over the past few decades have pushed economists more and more toward the study of monopsony power—particularly firms’ monopsony power over workers. Antitrust policy has taken notice. For example, when the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) initiated the process of updating their merger guidelines, their request for information included questions about how they should respond to monopsony concerns, as distinct from monopoly concerns.

From a pure economic-theory perspective, there is no important distinction between monopsony and monopoly power. If Armen is trading his apples in exchange for Ben’s bananas, we can call Armen the seller of apples or the buyer of bananas. The labels (buyer and seller) are kind of arbitrary. It doesn’t matter as a pure theory matter. Monopsony and monopoly are just mirrored images.

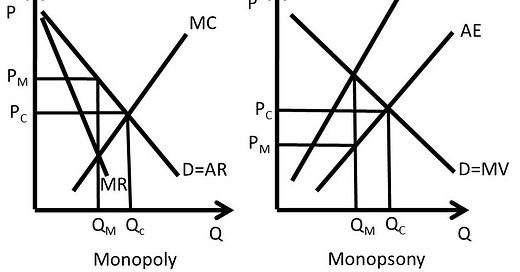

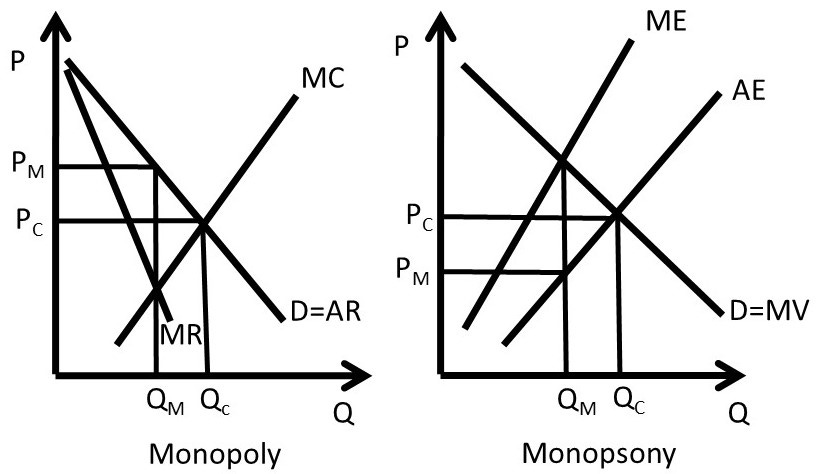

Even the monopsony graph looks like a confused student flipped monopoly upside down. Trust me, lots of students flip things upside down, like when they draw demand sloping up and supply sloping down.

The symmetry is true at a pure theory level. However, some infer from this monopoly-monopsony symmetry that extending antitrust to monopsony power will be straightforward. We need to be more careful at a more applied price theory level, where we are using the models for a particular purpose. As a practical matter for antitrust enforcement, it becomes less clear. The moment we go slightly less abstract and use the basic models that economists use, monopsony is not simply the mirror image of monopoly. The tools that antitrust economists use to identify market power differ in the two cases.

Monopsony Requires Studying Output

Suppose that the FTC and DOJ are considering a proposed merger. For simplicity, they know that the merger will generate efficiency gains (and they want to allow it) or market power (and they want to stop it) but not both. The challenge is to look at readily available data like prices and quantities to decide which it is. (Let’s ignore the ideal case that involves being able to estimate elasticities of demand and supply.)

In a monopoly case, if there are efficiency gains from a merger, the standard model has a clear prediction: the quantity sold in the output market will increase. An economist at the FTC or DOJ with sufficient data will be able to see (or estimate) the efficiencies directly in the output market. Efficiency gains result in either greater output at lower unit cost or else product-quality improvements that increase consumer demand. Since the merger lowers prices for consumers, the agencies (assume they care about the consumer welfare standard) will let the merger go through, since consumers are better off.

In contrast, if the merger simply enhances monopoly power without efficiency gains, the quantity sold will decrease, either because the merging parties raise prices or because quality declines. Again, the empirical implication of the merger is seen directly in the market in question. Since the merger raises prices for consumers, the agencies (assume they care about the consumer welfare standard) will let not the merger go through, since consumers are worse off. In both cases, you judge monopoly power by looking directly at the market that may or may not have monopoly power.

Unfortunately, the monopsony case is more complicated. Ultimately, we can be certain of the effects of monopsony only by looking at the output market, not the input market where the monopsony power is claimed.

To see why, consider again a merger that generates either efficiency gains or market (now monopsony) power. A merger that creates monopsony power will necessarily reduce the prices and quantity purchased of inputs like labor and materials. An overly eager FTC may see a lower quantity of input purchased and jump to the conclusion that the merger increased monopsony power. After all, monopsonies purchase fewer inputs than competitive firms.

Not so fast. Fewer input purchases may be because of efficiency gains. For example, if the efficiency gain arises from the elimination of redundancies in a hospital merger, the hospital will buy fewer inputs, hire fewer technicians, or purchase fewer medical supplies. This may even reduce the wages of technicians or the price of medical supplies, even if the newly merged hospitals are not exercising any market power to suppress wages.

The key point is that monopsony needs to be treated differently than monopoly. The antitrust agencies cannot simply look at the quantity of inputs purchased in the monopsony case as the flip side of the quantity sold in the monopoly case, because the efficiency-enhancing merger can look like the monopsony merger in terms of the level of inputs purchased.

How can the agencies differentiate efficiency-enhancing mergers from monopsony mergers? The easiest way may be for the agencies to look at the output market: an entirely different market than the one with the possibility of market power. Once we look at the output market, as we would do in a monopoly case, we have clear predictions. If the merger is efficiency-enhancing, there will be an increase in the output-market quantity. If the merger increases monopsony power, the firm perceives its marginal cost as higher than before the merger and will reduce output.

In short, as we look for how to apply antitrust to monopsony-power cases, the agencies and courts cannot look to the input market to differentiate them from efficiency-enhancing mergers; they must look at the output market. It is impossible to discuss monopsony power coherently without considering the output market.

In real-world cases, mergers will not necessarily be either strictly efficiency-enhancing or strictly monopsony-generating, but a blend of the two. Any rigorous consideration of merger effects must account for both and make some tradeoff between them. The question of how guidelines should address monopsony power is inextricably tied to the consideration of merger efficiencies, particularly given the point above that identifying and evaluating monopsony power will often depend on its effects in downstream markets.

This is just one complication that arises when we move from the purest of pure theory to slightly more applied models of monopoly and monopsony power. Geoffrey Manne, Dirk Auer, Eric Fruits, Lazar Radic and I go through more of the complications in our comments summited to the FTC and DOJ on updating the merger guidelines.

What Assumptions Make the Difference Between Monopoly and Monopsony?

Now that we have shown that monopsony and monopoly are different, how do we square this with the initial observation that it was arbitrary whether we say Armen has monopsony power over apples or monopoly power over bananas?

There are two differences between the standard monopoly and monopsony models. First, in a vast majority of models of monopsony power, the agent with the monopsony power is buying goods only to use them in production. They have a “derived demand” for some factors of production. That demand ties their buying decision to an output market. For monopoly power, the firm sells the goods, makes some money, and that’s the end of the story.

The second difference is that the standard monopoly model looks at one output good at a time. Here the word standard is key. In our first 100 models of monopoly, they sell one good. But the standard monopsonist (factor-demand) model uses two inputs, which introduces a tradeoff between, say, capital and labor. That means we have to worry about substitution, not just scale effects. We could be observing substitution effects away where the merged parties are hiring fewer technicians but are hiring more nurses and incorrectly attribute that to scale effects where they just buy fewer inputs, period.

We could force monopoly to look like monopsony by assuming the merging parties each produce two different outputs, apples and bananas. An efficiency gain could favor apple production and hurt banana consumers. While this sort of substitution among outputs is often realistic, it is not the standard economic way of modeling an output market.

My argument is not meant to imply that all comparisons to monopoly are unwarranted or that antitrust should never apply to monopsony because of these complications. My only point is that there are similarities and differences, and the economist needs to be careful jumping from one case to the other. I view economic theory as a form of criticism where we examine and critique logic or as a “prophylactic against popular fallacies,” as Henry Simons put it.