There Is No Such Thing As Supply

It's demand, all the way down

In how many posts have we talked about supply and demand? More than one?

There’s one minor problem: There’s no such thing as supply. It’s demand all the way down.

When we usually talk about demand, we mean consumer demand. There are people out in the world that do not currently possess the good but would buy the good at some price.

This is in contrast to producers who currently have the good and are willing to sell for some price. But what about any price below their reservation price? Then they want to keep their own good instead of selling it, aka they demand the good.

Let’s call this combination of demand total demand; it is the demand from both people who currently possess the good and those that do not currently possess the good.

PRODUCER DEMAND?

The difference between total demand and total consumer demand is the producer demand. Producer demand seems like a contradiction but we can see it from a simple point: Producers do not sell at just any price. They are implicitly demanding their own good.

For example, I cannot go to the BMW dealership and offer $1 for the new i8 and get it. Yet, no other consumer is there right now. It seems I am the highest demander there. Why not sell it to me?

While I’m not currently bidding against any other consumer, I am bidding against the current owner, which is the dealership. As is usually the case with firms, it is not that the dealership directly values the car in the same way that I do. Instead, they have a derived demand for holding the car, which is derived from the expectation of selling the car in the future. This is similar to how firms have a derived demand for workers, which is derived from the expectation of selling the products of the workers in the future.

Because the producers demand the car and their demand is above mine, they “receive” the good. By forgoing the dollar that I offer them, they are effectively buying the car for $1. If they did not demand the i8, they would sell it for any price and it was up to customers to bid it up from $0.

This concept can be illustrated using a graph similar to the standard supply and demand. Here total demand is TD. It consists of consumer demand (D) and supplier demand (which is a reverse of supply, S). The equilibrium price is where the total demand (TD) equals the total supply (stock), not just the standard supply. This supply is the amount that actually would exchange hands at a certain price. The TD/stock equilibrium price will be the same as the intersection of traditional D and S.

This is a now-forgotten tool that I first discovered in Man, Economy, and State, as shown below.

One possible downside of the TD/stock graph is that it does not show how much of the good actually exchanges hands, usually labeled Q*. The TD/stock graph looks the same if all the original holders of a good sell them or if none do.

But why does the number of goods that actually exchange hands matter? One counter-intuitive point is that it does not really matter. The number of transactions really doesn’t matter.

We can see this in Alchian and Allen’s explanation of the same idea. (HT to Sergio Martinez for reminding me that it’s in A&A. I have a habit of forgetting what is in A&A vs. what are my own, creative thoughts.)

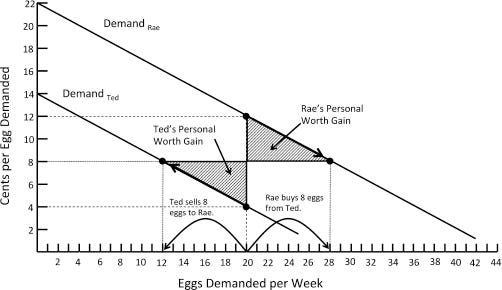

Consider a world where Rae and Ted have a demand for eggs and each starts with 20 eggs. However, Rae values eggs more than Ted and so they trade until there marginal value is equalized. Alchian and Allen’s figure is below.

Here it becomes clear that what we call “supply” is an artificial construct that is just a by-product of the initial allocation of eggs. As David Glasner points out, this is just a version of Stigler’s Coase theorem. In a world without transaction costs, the final allocation doesn’t depend on the initial allocation of property rights. If initial property rights don’t matter, the market is completely determined by the relative demand. Supply doesn’t add anything. Quantity traded doesn’t matter for welfare.

ECONOMICS AS TOOLBOX

At a conceptual level, I like this approach because it helps us avoid the Marshallian fallacy that there is a subjective side (consumers) and an objective side (producers) of the economy. It’s all just demand; it’s all subjective. When we think of producers demanding their own goods, we avoid this false dichotomy. It also may help us all avoid silly things like assuming that supply curves are horizontal in the long run. There is no reason to assume that, just as there is no reason to assume demand curves are horizontal.

At a less abstract level, TD/stock curves are another example of how clear economic thinking can improve our understanding and help us avoid a few mistakes.

First, suppose only a few shares of a company trade in any day. People may claim that this does not reflect the “true” market price since the price would drop if many stocks came on the market. However, this drop would only happen if the current holders lower their demand to hold stocks. They will try to sell the stocks if the current market price is above their group evaluation of the “true” price. Instead, everyone who is holding the cash values it above the market price. An equilibrium price always reflects the price where total demand equals the stock. It is impossible for it not to.

Second, imagine there is an economic good, say money, which has a low quantity traded in any time period. Some would be tempted to say that this money is idle or not “flowing” in some sense. However, this does not show that the goods are idle or not serving their most valuable purpose. All goods are always possessed by someone. At any point, they are never “flowing.” In the case of money, a low quantity traded only shows that the most valuable use of the money is in cash-balances in some period.

The question is not whether the money is idle since it is obviously serving its most valuable purpose at the moment. Whether its most valued use is to those who had it last period or not is irrelevant. They are both the same thing.

The fact that trade is small is not important. Instead, if worried, we should be asking why are banks holding money? What is the uncertainty that makes cash balances the most desirable use of the money? Is it some distortion of incentives? Or is the world just naturally uncertain and banks want to hold money?

Further Clarifying My Own Thinking

In a previous post, I claimed that a chip shortage for new cars would hit the used car market twice. First, the shortage raises the price of new cars, which are substitutes for used cars. This shifts out demand for used cars, driving up the price. In addition, I claimed it would shift in the supply of used cars since people would be less willing to sell their used cars and upgrade to new cars.

I claimed this was a double whammy on the used car market, which could lead the used car market price to rise more than the new car price. After an exchange with Nick Rowe on the topic, I now think that's at least misleading. I’m double-counting the shifts.

Besides minor flexibility about how much to fix used cars, the stock of used cars is fixed. The total stock is vertical as above. Then we only have one demand curve, the total demand. Yes, the total demand will shift out when new car prices rise, but is it plausible to shift enough to drive the used car price up more than the new car price? What do you think?

Author has changed underlying definitions of demand and incorrectly. Demand presumes you do not have and wish to have. Supply means you already possess it. Therefore, you can’t ‘demand’ something you already possess: if so, pay yourself $100,000 for your own car. Also, a supply curve at the start is near zero…

Cool concept! Might work even better explaining real estate. I'll have to think it through.

When prices go up, isn't the supply (for sale) supposed to increase? But that doesn't seem to work in real estate except maybe over the long run, years.

In the short run, following the double-demand idea, it could be that higher prices increase the demand from current owners. Owners like to hold stuff more when it's increasing in value more, so supply falls instead of increases when prices are increasing fast.

Then combine that with incredibly inelastic stock of houses (versus supply of houses for sale).

https://twitter.com/JohnWake/status/1471221496861249540?s=20