Was the Continental Dollar an Early Failure with Fiat Money?

Lessons in emergency finance

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 20,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

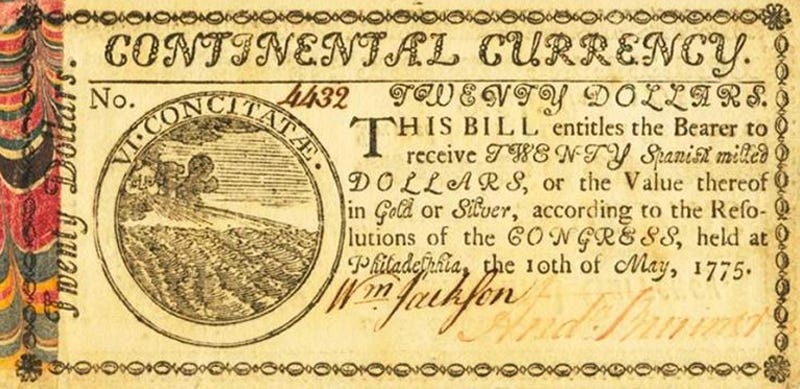

Although you will hear very few people say it today, there is a famous phrase in the American lexicon: “not worth a Continental.” The reference is to the Continental dollar, which was used by the United States during the Revolutionary War to help finance the war. Any measure of the purchasing power of the Continental dollar shows a dramatic deterioration over the course of the war, hence the famous phrase. A common narrative is to interpret the history of the Continental dollar as a typical story of paper money in which an excessive quantity is produced, resulting in a commensurate decline in its purchasing power.

But is that an accurate story of the history of the Continental dollar? In a (relatively) new book, Farley Grubb argues that this story isn’t correct. Along the way, Grubb’s alternative explanation provides a great application of price theory and relates to a number of topics I have written about at length here at Economic Forces.

For today’s post, I would like to present a basic version of Grubb’s argument, how it fits with previous themes I’ve written about, and explain why I find his argument compelling. Interested readers should refer to his book for additional details and history.

Defense and Emergency Finance

Frequent readers of the newsletter are by now familiar with the arguments I’ve made about the Treasury Standard. My general view is that the state’s monopoly on money is motivated by the need for emergency financing. Stated succinctly, there are times when states need to raise a lot of revenue in a short period of time. Doing so through taxation is difficult. Constituents (or even subjects) do not like wild fluctuations in their tax rates. A monopoly over money accomplishes that goal, whether it be through a monopoly of the mint, central banks, or the use of a nation’s debt instrument as a reserve asset for the rest of the world.

The Continental dollar is no different. When the Revolutionary War began, the United States were (yes were, not was) just a collection of colonies. The Second Continental Congress was convened but lacked the power to tax. The creation of the Continental dollar was used to finance the war. Initially, much of the emissions of these paper dollars were used to pay soldiers. Later, they were used to buy military equipment and supplies. Thus, like other experiments by the state in issuing money, the purpose was to finance a war.

The Last Period Problem and the Design of the Continental Dollar

Frequent readers of this newsletter will also recall that I like to reference a particular problem with issuing a new type of money. This problem is the so-called “last period problem.” When introducing a new type of money, one needs to generate a network effect. People will use the money if they expect others to use it. However, imagine a “last period.” Suppose there is some period in the future in which people are no longer willing to accept this form of money. If that is the case, then one shouldn’t accept this type of money in the prior period. Through backward induction, one should realize that the money shouldn't be accepted in the present.

One way to solve the last period problem with paper money is to make it redeemable for some commodity, like gold or silver. In that case, if there’s a point at which no one is willing to accept the paper as money, there is one particular seller who is required to accept the paper in exchange for a commodity at a fixed price. Thus, although one might not have any direct use for the commodity, the commodity has value independent of its use as money. In that case, one doesn’t have to worry about accepting a potentially worthless piece of paper in the last period, and the network effect isn’t so tenuous.

From time to time, people make the argument that taxation can also resolve the last period problem. The argument is as follows: Suppose that a state promises to accept paper money to resolve one’s tax liability; then everyone should be willing to accept the paper money in the course of normal exchange because they know that, at the very least, there is someone who is willing to accept the paper money if they are stuck holding it.

The tax argument provides an interesting thought experiment. The standard argument is that, in equilibrium, the supply of currency must equal the demand for currency. As Earl Thompson articulated, in this sort of a system in which currency can ultimately be used to pay for taxes, the demand for currency should be equal to the aggregate tax liability. Suppose that the taxes levied are income taxes. Given the supply of currency and the tax rate, nominal income must adjust to ensure that the demand for currency equals the supply.

Suppose the state issues a given quantity of currency and that currency can be used to pay an equivalent dollar amount of taxes in the future. Assuming that the currency is accepted at face value, we would expect that the issuance of the currency would cause the price level to “jump” to a higher level. Then, as the period in which the taxes are to be paid approaches, the price level should fall towards its previous level. The jump in the price level and the subsequent gradual decline should be sufficient to compensate those holding money over this time.

Alternatively, but equivalently, we might think of the paper currency as resembling something like a savings bond. In that case, the price level would not “jump.” Instead, the paper currency would initially trade at a discount, but over time, this discount should shrink as it converges to its face value when the taxes are due.

This insight is particularly important for the Continental dollar. Grubb’s argument is that the Continental dollar was never a fiat currency, as is often claimed. Instead, the Continental dollar was designed to be a zero-coupon bond, like a savings bond. At the same time, the Continental dollar was used as a medium of exchange. As such, we need to use this taxation-based model of currency to understand the Continental dollar system and why it ultimately lost its value.

The Design

I will begin by discussing the initial design of the Continental dollar and focus on that structure. Subsequently, I will discuss some changes that were made to the system and Grubb’s interpretation of how these changes influenced the Continental dollar’s value.

The Continental dollar was introduced in 1775. The denomination of the Continental dollar was set equal to the Spanish silver dollar. Nonetheless, the way the system was designed was such that the Continental Congress could emit Continental dollars to pay soldiers (and later to pay for military equipment and supplies). Each of the colonies was then given a quota of Continental dollars to return to the Congress to be destroyed. It was left to the states to determine how to meet these quotas. The most obvious example was taxation payable in the Continental dollar. If colonies couldn’t meet their quotas, they were required to submit the corresponding amount of specie to the Congress. Anyone holding a surplus of Continental dollars could redeem them for specie at face value. The first required quotas would begin four to seven years after this initial emission (in line with the expected length of the conflict).

During the early years of the Revolutionary War, Continental dollars were largely spent as wages paid to soldiers. Spending Continental dollars into circulation wasn’t difficult because the soldiers could not refuse them. However, as the war continued, Congress needed to purchase equipment and supplies. They found that suppliers could and would refuse to accept Continental dollars as payment. As a result, in 1777, the Continental Congress asked states to give the Continental dollar legal tender status in their states.

Quotas were designed to be proportional to each colony’s percentage of the overall population. Furthermore, the annual redemptions were roughly equivalent to the average level of taxation in the colonies during this period.

But how do we know that the intent of the Continental dollar was to serve as a zero-coupon bond rather than a fiat currency?

One reason that we know the intent was to issue zero-coupon bonds is that the denomination size was much too high for a typical medium of exchange. The Continental Congress never printed anything below one dollar, which, according to Grubb, would be equivalent to $31 in 2012 US dollars. If the smallest bill was this size, it is hard to imagine that they intended these to be used as a medium of exchange.

A second clue is that the pay of Revolutionary War soldiers was set in terms of the Continental dollar. Soldiers were paid 80 Continental dollars per year. This was dramatically higher than the 55 dollars per year that a British soldier earned. However, assuming that the Continental dollars were redeemable at face value four to seven years hence, and using a 6 percent discount rate, the present value of the Continental dollars paid to the revolutionary soldiers would be between 53 and 61 dollars per year. The fact that the present value was more in line with market prices for military service than the face value also implies that policymakers recognized the Continental dollar as a zero-coupon bond.

Explaining the Value and the Decline of The Continental Dollar

We know that the Continental dollar traded at a discount to its face value. But how much of a discount, and how do we know? Unfortunately, much of the data we have to evaluate this comes from indirect sources. In fact, measures of the price level are often used to track the purchasing power of the Continental dollar. From this purchasing power, we can potentially estimate the discount on the face value.

If the Continental dollar should really be thought of as a zero-coupon bond, then the value of the Continental dollar (whether measured by its discount or through its purchasing power) should be consistent with this valuation process.

Grubb estimates the present value of the average Continental dollar and finds that the present value of the Continental dollars is consistent with the measures of purchasing power through 1779. This is therefore consistent with the view I put forth earlier about taxation-valued money. Once Continental dollars became legal tender, they were more likely to circulate. Furthermore, as additional Continental dollars were introduced, this did cause the price level to rise, but only because the marginal present value of the new Continental dollars was lower than the average present value of the existing supply. Had Congress stuck to its initial redemption scheme, then the discount on Continental dollars would have declined as they gradually approached their face value.

Ultimately, however, the value of the Continental dollar collapsed. The reason, however, wasn’t simply due to the increase in supply. Rather, the collapse of the value of the Continental dollar came as a result of attempted reforms in 1779 and 1780 that communicated a lack of fiscal credibility. Specifically, the reform removed legal tender status and was designed to dramatically increase the quotas from the states to expedite the return of Continental dollars for their removal from circulation. However, this wasn’t credible. Doing so would have required states to increase taxation levels at least an order of magnitude greater than the norm. Given the unbelievable scale of taxation that this would require, people (correctly) began to anticipate that they would not be repaid the face value of (at least some fraction of) their Continental dollars, and the value collapsed.

Some General Lessons

There are a couple of reasons that this particular historical experience is important. First, it demonstrates that not all attempts at generating emergency finance actually result in durable institutions. In a number of my previous posts, I often detailed successful cases or how societies evolved from one successful institution to another. However, this isn’t always the case. History is replete with trial and error. The failures teach us something as well. The critical feature of a successful emergency financing scheme is the credibility to commit to future actions.

A second reason that this episode is important is that this is just basic price theory at work. Yes, it really is just supply and demand. However, this experience illustrates why it is important to go beyond “it’s all just supply and demand” and dig deeper. After all, the conventional story is that the Continental dollar lost its value because of an over-supply of fiat money. However, what Grubb’s work demonstrates is that the collapse in value actually corresponds with a reduction in demand associated with the lack of fiscal credibility communicated by those reforms.

Confederate (CSA) money would be an altogether different (regime dissolution) case?

DON'T lose the war! Or the regime, anyway.