You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 12,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

If you follow the news, you've probably heard a lot of discussions lately about rising market power, market concentration, and markups. If you’re a bit more of an econ nerd, you’ve maybe heard that business dynamism has dropped off a cliff (at least before COVID-19). Some people look at the trends and see a clear sign that competition is dying. Cats and dogs, living together, mass hysteria!

Are rising market power and falling dynamism related?

That’s what Ryan Decker (of business dynamism research fame, but more importantly, of old blogging fame) and I started exploring in a new contribution to FEDS Note. As I’ve learned to add to my presentations, the findings “do not indicate concurrence by members of the Federal Reserve staff or the Board of Governors.” What I say in this humble newsletter does not even indicate concurrence by Ryan.

Snark aside. The aggregate time series trend is pretty striking. Up through 2017 (the latest date we use), different measures of markups steadily rose, and measures of dynamism—such as new business entry rates and worker turnover rates—fell. Not great, Bob!

There has been some work trying to connect these two time-series theoretically and lots of commentary that connects them. However, as we point out:

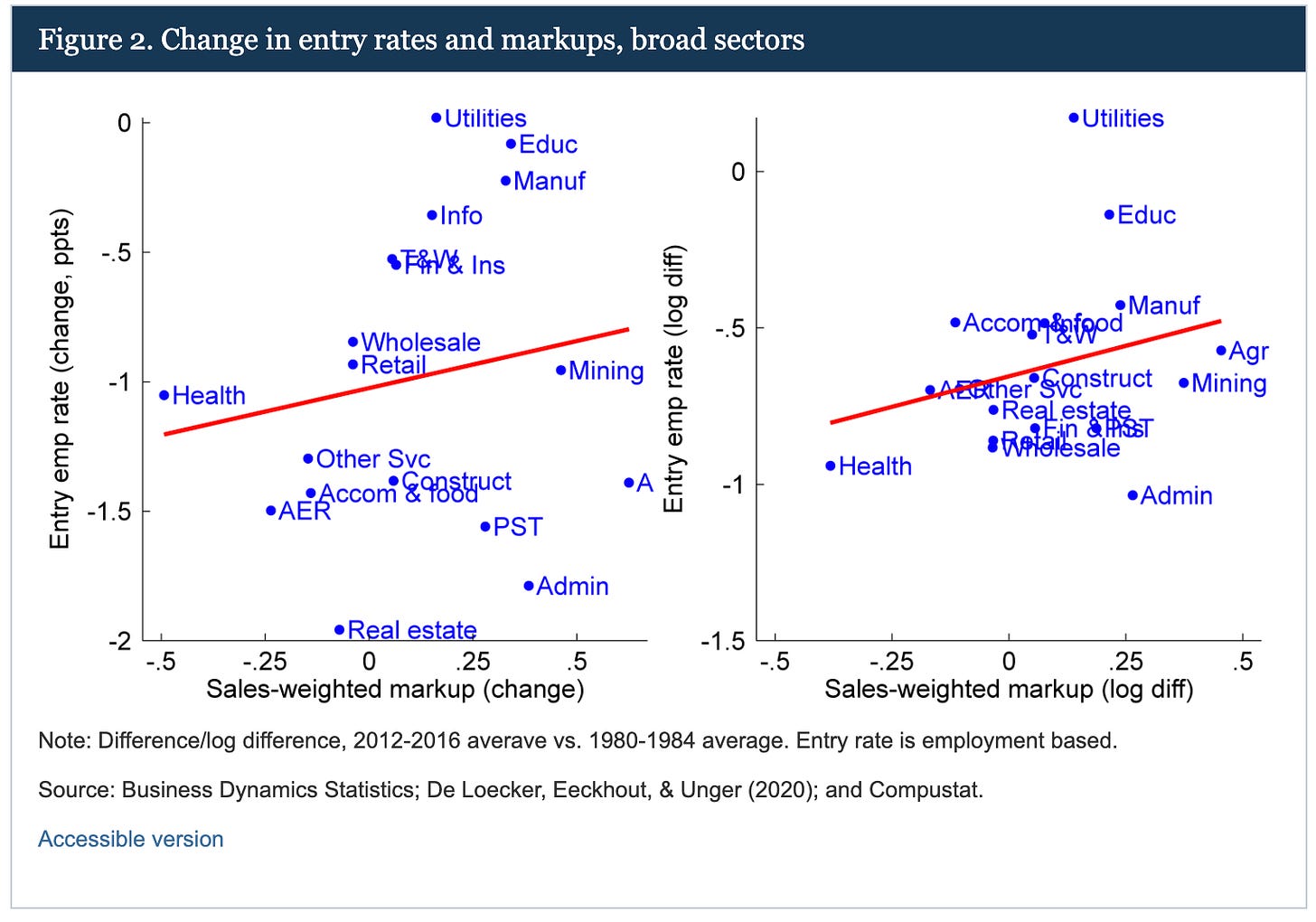

The industry-level evidence does not support the notion that the aggregate time series for markups and business dynamism are causally related. In fact, if anything, the opposite relationship is apparent in the data: from the early 1980s through the mid-2010s, industries with larger increases in markups saw a smaller decline in dynamism.

The clearest example is Figure 2.

The note has more details. I encourage readers to check it out.

Why the correlation?

Let’s start by assuming you’re skeptical of these correlations. I mean, it’s weird to be skeptical of a correlation. It’s there. I showed it to you. But suppose you’re skeptical of what the correlations imply about other things. You’ll ask, why do we get this misleading result? It's a great question, and to be honest, we don’t have a definitive answer yet. But we've got some ideas.

A basic one we don’t mention in the note is that our industry definitions don’t capture what theory says we should look at. We rely on 2-digit and 3-digit NAICS codes to define industries, which are quite broad and lump together many firms that are not in what IO economists would think of as “the same industry.” Similarly, there could be spillovers between industries that we are not taking account of.

The other issue may be that the markup estimates only cover publicly traded firms. As I’ve explained before, that's a small slice of the overall business population, and public firms are a weird bunch. They behave differently than private firms in all sorts of ways, including their dynamism patterns. So the markups we estimate from public firms might not be telling us the full story.

The other option is that our markup measure is giving us weird results, especially when we split it up by industry. We cite a debate in the econometric literature over the proper way to measure markups. That debate is on top of the points I’ve made before about markups being a residual and not necessarily the inefficiency some people assume they are. It’s possible the markup measure is not quite capturing what we want it to capture from a theoretical perspective.

What’s the theory?

Speaking of theory, something that has been absent in what is supposed to be a price theory newsletter, we don’t seriously deal with the theory in the note. It’s a note, not a full paper. But there are a couple of basic Economic Forces out there that give us some useful ways to think about the issue.

The first is what I’ll call the “barriers to entry” story. The idea is pretty intuitive: if there are high barriers to entry in a market (think regulations, high fixed costs, network effects, etc.), it’s harder for new firms to come in and compete. Existing firms can charge higher markups and face less pressure to innovate or adapt. In this view, rising markups should be associated with declining dynamism. This seems to be the story everyone has in mind when thinking about dynamism and market power. A few papers explicitly make this link, such as Akcigit and Ates, De Ridder’s JMP, and De Loecker, Eeckhout, and Mongey. All very good papers.

On the flip side, there’s what I’ll call the “free entry” story. I’m being fast and loose, but this is a newsletter. This one comes straight out of Econ 101. If firms are making big profits, that should attract a bunch of new entrants looking to get a piece of the action. More entry means more dynamism. Profits are not the same thing as markups, but they’re related. So, in this view, high markups should be associated with more dynamism, not less.

So which is it? Are we in a world of barriers to entry or free entry? The real world is probably a mix of both, and it might vary significantly across industries and over time. Our simple correlations suggest a mix, slightly leaning toward the free entry story.

Our results suggest that the neat barriers to entry story, with its simple connection between rising market power driving declining dynamism, doesn't quite straightforwardly fit the industry-level evidence. But that doesn't mean the story is totally wrong—it just means we need to dig deeper and think harder about what's really going on.

Economics is all about puzzles, and this is a great one. We've made some progress, but there's still more to figure out. The relationship between markups, competition, and dynamism is complex, and it will take a lot more work to understand it fully. But that makes this stuff exciting—there's always more to learn!