Why no one likes land taxes

Inefficient taxes constrain government

Economists and [insert basically every other group of people] don’t often agree. Take, for instance, the recent discussion of price controls. The title of Sunday’s NYT opinion piece literally starts “Economists Hate This Idea.” Yet voters aren’t so skeptical. (I’m not ready to say it has the popularity that piece claims.)

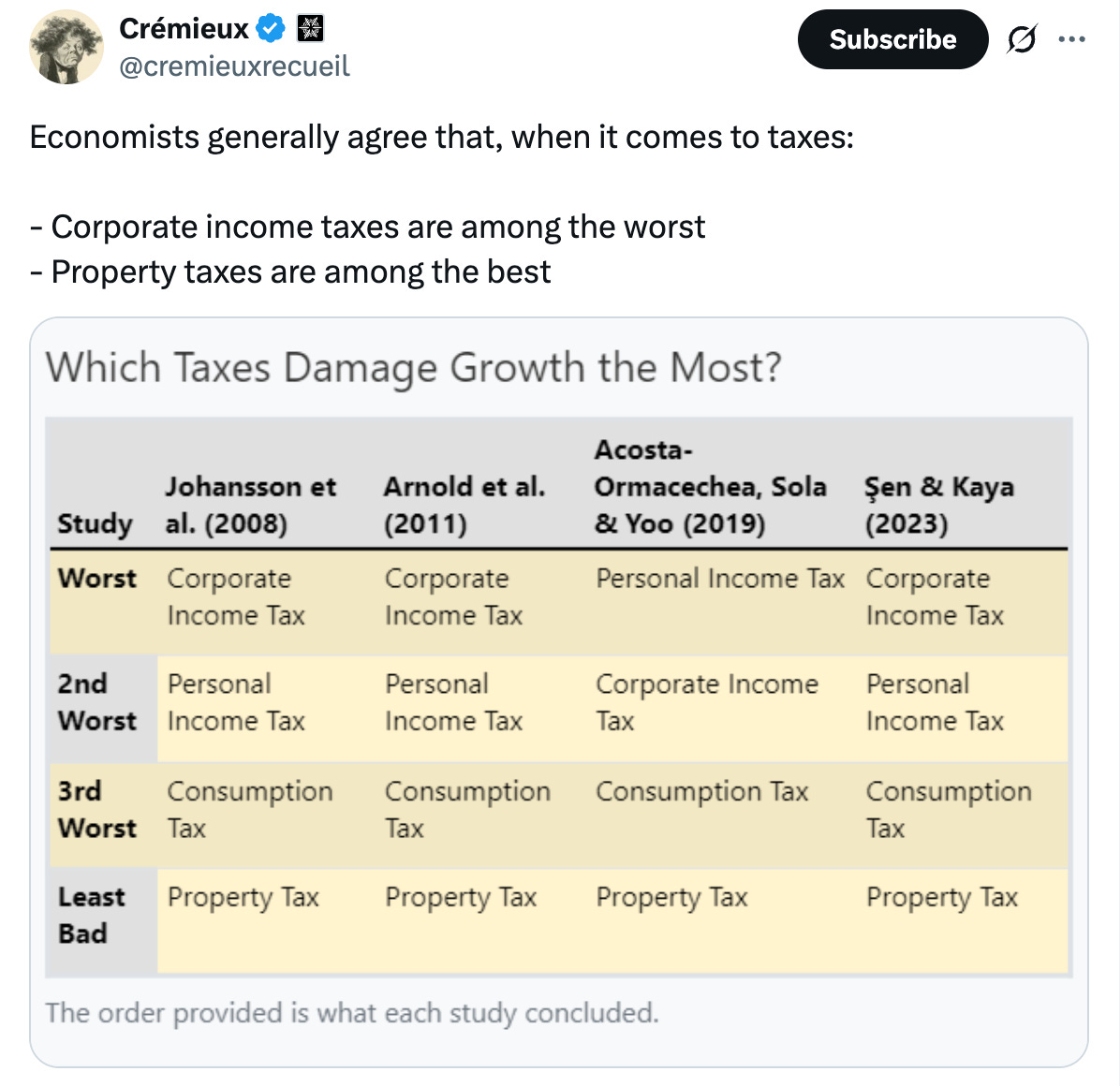

Another area of disagreement is taxation. Economists tend to prefer taxes like property taxes; voters despise them. Economists think corporate taxes are among the worst ways to raise revenue; voters think corporations should pay more. Economists generally prefer consumption taxes to income taxes, whereas voters tend to prefer income taxes.

I say “prefer” and “think,” but it’s not just some whim. It pops out of many models and there’s research pointing in the same direction.

Byrne Hobart recently started a great piece with this puzzle. Ask an economist about property taxes, and they’ll explain that the land part is fixed in supply (not much distortion there), impossible to hide, and therefore ideal to tax because taxing it doesn’t distort behavior. Ask a median voter about property taxes, and you’ll hear complaints about paying rent to the government on something they already own. As Hobart puts it, “the things voters hate about property taxes are the things economists love about them.”

If I’m being honest, the standard economist reaction is to be dismissive of voters. Economists when being more careful will say voters are “rationally irrational,” since one vote rarely decides an election, and voters have little incentive to learn the true costs of different tax systems. Ignorance about big topics like taxes is individually rational even when it’s collectively costly.

But this explanation is a little too convenient. People know property taxes fund local schools. They know sales taxes are just as real as income taxes. Often, in this newsletter, we stress that maybe people understand something that the baseline model misses. As Hobart puts it, “Tax systems are never optimal, but that’s its own kind of market efficiency at work.” So what is that efficiency?

Notice that the ranking above is in the context of growth as a proxy for things like deadweight loss, things that hold back an economy. There’s a political dimension missing in most growth models. Josh and I have a paper with Alex Salter on defense and growth. We argue defense is central to understanding economic growth. It’s not a controversial statement to say political economy or institutions (beyond just tax rates) matter for economic growth.

So maybe our models of taxation should have more to say about political economy. Some do!

In today’s newsletter, I want to go through two economic models that explain why voters prefer “inefficient” taxes. The first, from Gary Becker and Casey Mulligan, argues that inefficient taxes create political resistance that keeps rates low. The second, my own take on a model from David Friedman’s work on punishment, argues that inefficient taxes prevent the state from becoming too aggressive in extraction.

Think of taxation as a conflict between the state trying to extract and taxpayers trying to resist. The Becker-Mulligan model focuses on the defender: inefficient taxes hurt enough to keep taxpayers vigilant and politically mobilized. That’s the demand side of policy. The Friedman model focuses on the attacker: inefficient taxes make enforcement unprofitable, so the state backs off. That’s the supply side of policy. Both models give political economy reasons for why we see so little “efficient” taxation.

Property taxes aren’t land taxes

Before proceeding, we need to clarify what economists mean when they praise property taxes for efficiency. This strong argument really applies to land value taxes, which are taxes on the unimproved value of land itself. The basic argument is that land supply is fixed (basically). Yes, there are proposals to add to Manhattan but you’re not going to create more Manhattan or destroy existing farmland in response to tax rates. A tax on pure land value, therefore, creates no deadweight loss. The land exists regardless of the tax. It’s just a transfer from land owners to the government.

If land value taxes are so efficient, why don’t we use them? Part of Mike Bird’s new book, The Land Trap, actually traces how Henry George’s 19th-century movement for a “Single Tax” on land values attracted followers but basically failed to be implemented in practice. What we got instead is the property tax, which is more complicated. They tax both land and the improvements on it. This “capital” component definitely responds to taxation. If you tax buildings, people build less. If you tax renovations, people renovate less. The capital component of property taxes creates deadweight loss just like any other capital tax.

This distinction matters for the analysis that follows. The efficiency case for property taxes rests entirely on the land component. The capital component undermines that case. Real-world property taxes blend both, making them less efficient than the theoretical ideal but more efficient than pure capital taxes. That’s where the empirical literature above matters. It tries to measures these trade-offs.

The Becker-Mulligan Model

Enough of those real world complications. Let’s get to some models. (I’m half joking.)

The key idea from Becker and Mulligan is that painful taxes stay small.

In the conventional view, a tax with low deadweight loss is good because it raises revenue without distorting economic decisions much. A head tax, where everyone pays the same amount regardless of behavior, has zero deadweight loss. A tax on land has nearly zero deadweight loss because the supply of land doesn’t respond to price. An income tax has higher deadweight loss because it discourages work. Excise taxes on specific goods have even higher deadweight loss because they push consumers toward untaxed substitutes.

Becker and Mulligan argue that this ranking reverses when you account for political economy. Taxes with low deadweight loss don’t hurt much, so taxpayers don’t bother fighting them. Taxes with high deadweight loss are painful, so taxpayers spend resources lobbying against them. The result: efficient taxes grow large while inefficient taxes stay small.

I don’t want to scare anyone off with too much math so let’s keep it simple. Let R be government revenue and D be deadweight loss. Total social cost is R + D. The government wants to maximize some objective function that includes revenue. Taxpayers want to minimize R + D.

The key insight is that taxpayer political activity depends on the marginal cost of taxation, not just the average cost. If a tax is efficient (low D/R), then raising an additional dollar of revenue imposes little extra pain on taxpayers. They have weak incentives to resist. If a tax is inefficient (high D/R), then raising an additional dollar of revenue imposes substantial extra pain. Taxpayers have strong incentives to resist.

Becker and Mulligan write the taxpayer’s political pressure as a function A(D), where A increases with deadweight loss. When D is low, pressure is low. When D is high, pressure is high. This pressure constrains government revenue. The government maximizes revenue subject to the constraint that higher taxes generate more resistance.

The equilibrium features an inverse relationship between efficiency and tax rates. The most efficient taxes have the highest rates. The least efficient taxes have the lowest rates. Total revenue collected through efficient taxes exceeds total revenue collected through inefficient taxes.

Now turn this around from the voter’s perspective. If you could choose the tax system, would you want efficient taxes or inefficient taxes?

With efficient taxes, you save on deadweight loss per dollar of revenue, but you face a government that grows without limit because you never mobilize against it. With inefficient taxes, you waste resources on deadweight loss, but you stay vigilant and keep rates low.

Becker and Mulligan show that taxpayers can prefer inefficient taxes when the revenue effect dominates the efficiency effect. An inefficient tax that raises $100 with $20 of deadweight loss costs you $120. An efficient tax that raises $200 with $5 of deadweight loss costs you $205. You prefer the inefficient tax even though it has four times the deadweight loss per dollar of revenue.

While I’ve framed this newsletter around people hating property taxes, the flipside is also true. Voters are much more accepting of corporate taxes, even though economists are not. The model gives a reason; corporate taxes can be partially avoided through transfer pricing, debt financing, and jurisdictional arbitrage. They generate substantial deadweight loss through distorted investment decisions. But precisely because they are painful and easy to avoid, corporations fight them constantly. The equilibrium corporate tax rate stays lower than it would if corporate taxes were efficient.

The government expands whenever political pressure relaxes. It just grows when unconstrained, so voters use inefficient taxes as reins. The pain of inefficiency keeps them alert to rate increases. It’s a commitment device to stay vigilant in monitoring the government.

Why Not Hang Them All?

As I said, Friedman’s paper is about punishment. He asks why we use prison instead of fines. From your textbook economics perspective, fines are much better. The defendant loses money, the state gains money, and no resources are destroyed in the process. Prison is horrible from this perspective. The defendant loses years of freedom, and the defendant’s potential economic output is wasted. Unlike fines, where the state at least gets some money, the state here pays the costs. That’s the opposite of getting money.

There’s a somewhat standard law and economics answer that fines cannot adequately punish poor defendants. If someone commits a crime worth $100,000 in damages but only has $10,000, a fine can’t deter them. Prison fills the gap. There’s definitely something to that.

Friedman proposes a different answer. Efficient punishments create bad incentives for enforcers. If prosecutors and police capture most of the value they extract from defendants, they will prosecute too aggressively. They will frame innocent people for profit. They will target wealthy defendants with weak cases because the expected value is high.

Prison protects defendants by making prosecution unprofitable for the state. The state spends money on incarceration and receives nothing. Prosecutors have no financial incentive to convict innocent people because conviction doesn’t enrich them.

Friedman writes that the key variable is the “ratio of punishment cost to amount of punishment.” When this ratio is high (inefficient), enforcers have weak incentives to punish. When this ratio is low (efficient), enforcers have strong incentives to punish.

Apply this logic to taxation. The enforcer is the tax authority. The victim is the taxpayer. The “efficiency” of a tax is the ratio of revenue collected to resources spent on collection.

Property taxes are efficient in this sense. The tax authority knows what you own, knows what it’s worth (or can assess it), and can seize your house if you don’t pay. Collection costs are low relative to revenue. This makes property tax enforcement highly profitable for the state.

When enforcement is profitable, the state enforces aggressively. Tax assessors have incentives to value your property at the highest defensible level. The tax authority has incentives to pursue every dollar owed. Homeowners feel a pressure that’s different from sales taxes, including the threat of losing their homes.

Corporate taxes are inefficient in this sense. Corporations can shift income across jurisdictions. They can relabel equity as debt. They can use transfer pricing to move profits to low-tax subsidiaries. The tax authority must spend substantial resources investigating these structures, and even then, collection is uncertain. Enforcement is expensive relative to revenue.

When enforcement is unprofitable, the state enforces less aggressively. The IRS knows that auditing sophisticated corporate returns is expensive and often unsuccessful. They focus resources elsewhere. Corporations face less pressure per dollar of tax liability.

Putting the Models Together

For the first level that we touch in this newsletter, the Becker-Mulligan model and the Friedman model predict the same behavior (the use of inefficient taxes) but through slightly different mechanisms. In Becker-Mulligan, the problem is voter attention. If voters could commit to fighting all taxes equally, efficient taxes would be unambiguously better. The challenge is maintaining vigilance when taxes don’t hurt. In Friedman, the problem is state incentives. Even if voters paid perfect attention, efficient taxes would create enforcement agencies that maximize revenue rather than welfare. The challenge is constraining the state when enforcement is profitable.

I should admit to a bit of a bait and switch. I started by asking why voters dislike efficient taxes, but these models don’t really explain preferences or thought processes. Economics doesn’t do that. As Josh pointed out, price theory is about behavior.

The question isn’t why inefficient taxes are popular but why successful countries end up with them. Efficient taxes may be unstable: they either grow until they strangle the economy or provoke a political backlash that replaces them with something more painful. What we observe in thriving economies is what survives this selection process. It’s possible those selection criteria feedback to “intuitions.”

It’s plausible that real-world tax systems have a little of both. The U.S. relies heavily on income taxes, which are moderately efficient but generate enough pain (especially at filing time) to maintain voter attention. Property taxes fund local governments but remain controversial precisely because they are efficient enough to feel predatory. Corporate taxes are inefficient by almost any measure, but serve as a constant reminder to interested parties (interest groups for the win) that keeps rates from rising too high.

The standard economist recommendation is to move toward more efficient taxes: replace income taxes with consumption taxes, replace corporate taxes with shareholder taxes, and rely more on property taxes. I get it. That’s my default as well. But I need to recognize that this recommendation ignores political economy.

Voters aren’t wrong, at least not completely wrong, to distrust “efficient” taxes. They’re protecting themselves from governments that would otherwise extract too much. The deadweight loss of inefficient taxes is the price of keeping Leviathan in check.

Not to be cynical, but the average voter almost certainly thinks that corporation taxes are paid by corporations i.e. not by him. It's tariffs: polling generally shows that voters like them, but people think they are paid by foreigners.

People know they pay property taxes, so they object to them.

I think this is a very interesting analysis and the benefits of limiting the government's ability to tax might be worth it. I am very skeptical though that this is the reason voters don't like efficient taxes which is the article's hook. I even doubt that voters have any kind of intuition for these dynamics.

The real reasons are probably perceived fairness arguments which you alluded to earlier in the article. Even as someone who'd love to see LVT as the primary form of taxation, have some concerns about the tax basis for LVT being established accurately.