6 reasons why tariffs are a terrible way to raise revenue

Some principles of taxation

Economists are not fans of tariffs. There, the newsletter is coming out the gate with some hot takes! Meanwhile, regular people think tariffs are good for jobs. At the very least, they may ask, “What’s the big deal? It’s just a tax on imports. We need taxes to fix the deficit.”

To be clear, economists as a group don’t have the same reaction to other taxes. If a politician wants to raise the income tax, you’ll have a more balanced disagreement among economists. But tariffs? As Jason Furman put it,

Economists, including me, suffer from tariff derangement syndrome. We find ourselves disproportionately worked up every time they are increased.

So why do economists have such a visceral reaction to tariffs? I can’t speak for all economists, but I conjecture it is because tariffs violate basically all the principles of taxation that economists have developed over the past century plus.

The goal of this week’s newsletter is to explain that seemingly disproportionate reaction by focusing on why tariffs are a uniquely bad way to raise revenue. This isn’t about Trump or any specific policy proposal. Instead, it will be a general walk-through of the basics of taxation using simple models. If you want the empirical work, we have lots of other pieces on Economic Forces.

To understand the deep-seated skepticism economists have for tariffs, it helps to build our thinking from the ground up. Let’s not jump straight into the complexities of international trade and the modern models. I don’t think that’s what most economists use to think about tariffs. Instead, let’s imagine a few simple “toy” economies. By gradually adding realistic features, we can triangulate how tariffs go wrong as a way to raise money for the government.

Reason 1: Tariffs distort consumption

Let’s begin with the simplest possible economy. Imagine two islands, “Home” and “Foreign.” At Home, coconuts magically fall from the sky. In Foreign, bananas do the same. Naturally, the two islands trade. Two bananas trade for one coconut.

The government at Home needs to collect resources to fund public services, like building a seawall. What’s the best way to do this? By “best,” I mean what the people would prefer. I’m not worried about people disagreeing at this point.

The best, or if you want “efficient,” tax would be a broad consumption tax: a tax on both the coconuts consumed at Home and the imported bananas. The key is that it doesn’t distort the choice between eating a coconut or a banana. It maintains the relative price. People continue consuming the mix of fruit that makes them happiest—they just consume a bit less overall to pay the tax. This is a benchmark for an ideal tax.

Now, consider a tariff: a tax only on the imported bananas. This makes bananas artificially expensive. In response, people at Home will consume fewer bananas and more coconuts than they otherwise would, ending up with a mix of fruit that gives them less satisfaction. The tariff creates an inefficiency by distorting consumption choices.

The tariff creates an inefficiency by distorting consumption choices. People could be better off if the government just taxed both fruits lightly and equally and kept the relative price at 2 bananas per coconut.

What’s missing from this model? This world has no work or production; fruit just falls from the sky. That doesn’t tell us much. This is basically a lump sum tax which doesn’t distort any decisions because the coconuts just fall from the sky.

Reason 2: Tariffs distort both consumption and work

Let’s add work to our economy. The fruit no longer falls from the sky. At Home, islanders must choose between working to gather coconuts or enjoying leisure. In Foreign, they choose between working to gather bananas or enjoying leisure. Again, they trade at the same price: 2 bananas for 1 coconut.

Now the government at Home has three options for raising revenue. As before, it can use a broad consumption tax or tariffs. But now it can tax income as well. But actually, in a world without savings, the income tax is identical to a broad-based consumption tax. You can only spend what you earn, so it doesn’t matter if the 20% is when you get paid or when you buy goods. It’s the same.

So let’s compare this income tax option against a tariff on imported bananas.

The income tax creates one distortion (as would the consumption tax in this model): it makes leisure more attractive relative to work and can cause the total number of coconuts gathered to fall. That’s unfortunate, but it’s an inevitable cost of taxation.

But what if the government uses a tariff on imported bananas instead? This policy is worse because it creates two distortions. (In general, you can’t just add up the distortions to find the best policy but it’s helpful to think of there being two.)

First, like in the first endowment model, it distorts consumption by making bananas artificially expensive relative to coconuts. It also doesn’t help on the labor income side because, by making imported bananas more expensive, the tariff makes the reward for working (producing coconuts to trade for bananas) less valuable. If the bananas you can get for your coconuts become more expensive, working to gather coconuts becomes less attractive. This indirectly discourages work, just like the income tax did. So a tariff layers a consumption distortion on top of a work-leisure distortion, making it less efficient than a straightforward tax on income or general consumption..

What’s still missing? This model still misses a crucial feature of modern economies: the tools and equipment that make workers productive.

Reason 3: Tariffs reduce productivity

Now let’s add the most important realistic feature, which I think is the most important.

The economy at Home has “Climbers” who gather coconuts, but the economy in Foreign has “Weavers” who are skilled at making sturdy ladders. Ladders aren’t consumed for pleasure like fruit. They are a productive input that allows a Climber to gather far more coconuts. Home imports these ladders from Foreign, paying for them with coconuts. Let’s ignore importing bananas for consumption.

The government at Home, needing revenue, decides to place a tariff on imported ladders.

The result harms the economy’s productivity. The tariff makes ladders (a key tool for production) more expensive. Faced with this higher cost, some Climbers decide it’s no longer worth it to buy a ladder and go back to climbing with their bare hands. Their productivity plummets. The entire production system at Home becomes less efficient.

This illustrates the most important idea in optimal taxation, an insight from Peter Diamond and James Mirrlees: in quite general settings, you want the economy to be “productively efficient.” For productive efficiency, you should never tax intermediate goods. Unlike the first models, here the tariff destroys the production process itself, shrinking the entire economic pie before the government even gets a chance to tax the final slices.

This kind of damage is especially severe in modern supply chains, where goods cross borders multiple times before reaching the final consumer. Consider a car assembled in Michigan: its parts may come from Ohio, Ontario, and Oaxaca, crisscrossing borders throughout the production process. A tariff on intermediate inputs like car parts hits each time the good moves across a border, compounding costs at every stage. What looks like a 10% tax on a single import may effectively become a 30% tax on the finished product by the time all the parts are assembled.

Think about it this way: if you’re trying to raise tax revenue in the least destructive way, you want the economy to be as productive as possible first. Then you can tax the final output.

Now, you might be thinking: “But what if only rich Climbers can afford ladders? Shouldn’t we tax ladders to help redistribute wealth?”

This thinking is tempting but wrong. If you want to help people who can’t afford ladders, the efficient approach is to tax the ladder-owners’ income or final consumption and give the money to the ladder-less. Don’t tax the ladders themselves. Taxing ladders makes the whole economy less productive, hurting everyone—including the people you’re trying to help. You want as big a pie as possible to redistribute from.

The Diamond-Mirrlees insight is that production efficiency and redistribution are separate goals that should be handled separately: make the economic pie as big as possible, then redistribute slices of that pie through income taxes and transfers.

What missing? We had different capabilities on the production side but what about difference on the consumption side.

Reason 4: Tariffs are bad at redistribution

Now let’s think about the broader range of final goods people consume. Suppose our economy produces not just coconuts and bananas, but many different types of final goods: coconuts, bananas, papayas, mangoes, and so on. Some of these are produced domestically, others are imported.

The government needs revenue and is considering how to tax all these different final goods. Should it tax luxury goods like papayas more heavily? Should it give special treatment to “necessities” like coconuts? Should it tax imported goods differently from domestic ones?

This brings us to another huge public economics insight, this time from Anthony Atkinson and Joseph Stiglitz. They proved that, under reasonable assumptions, the optimal tax system should tax all final consumption goods at the same rate. The intuition is powerful: if you want to redistribute from rich to poor, it’s better to do it directly through progressive income taxes than indirectly by trying to guess which goods rich people buy more of.

The Atkinson-Stiglitz theorem says that once you’re following Diamond-Mirrlees and not taxing intermediate inputs, you should set the same tax rate on all final consumption goods. This creates the least distortion in people’s consumption choices.

Tariffs violate this principle directly. They tax only imported final goods, leaving domestic final goods untaxed or taxed at different rates. This creates artificial incentives for people to buy domestic papayas instead of imported ones, even when the imported ones might be higher quality or lower cost before the tariff.

What’s missing? Everything so far is static. But what really matters is growing the economy over time.

Reason 5: Tariffs are a tax on growth

Let’s extend our ladder example, but now think about what happens over time. Instead of each Climber just buying one ladder when they need it, imagine that ladders are durable and Climbers can accumulate them. The more ladders a Climber owns, the more productive they become—they can access higher branches, work multiple trees simultaneously, and gather far more coconuts.

Home imports these ladders from Foreign and, over time, builds up a stock of them. This stock of ladders is the economy’s capital—the accumulated tools and equipment that make workers more productive.

Now, suppose the government places a tariff on imported ladders. This doesn’t just affect the Climbers who want to buy a ladder today. It affects the entire process of capital accumulation in the economy.

With the tariff making ladders more expensive, fewer new ladders get imported each year. The economy’s stock of ladders grows more slowly. Some old ladders break down or wear out, and they’re not replaced as quickly because of the higher cost. Over time, the entire economy becomes less productive as the capital stock shrinks relative to what it would have been.

They harm the economy’s ability to become more productive over time. A tariff on capital goods is like a tax on economic growth itself. The third huge optimal taxation result, originally from Chamley and Judd, is that you don’t want to tax capital. See Chari, Nicolini, and Teles for the modern treatment.

The effects compound. With fewer ladders, workers are less productive. With lower productivity, the economy generates less income. With less income, there’s less money available to buy new ladders, even if the tariff were removed. The economy gets stuck in a lower-productivity equilibrium.

What’s still missing? What if there are a bunch of people accumulating ladders, but some people aren’t? They are losing out.

Reason 6: Tariffs invite wasteful rent-seeking

Let’s imagine Home has two types of coconut producers: a few highly efficient ones and many high-cost, inefficient ones. Foreign also produces coconuts, and they are cheaper than anyone at Home. Without trade barriers, the high-cost producers at Home would be driven out of business by competition from both the efficient local producers and the cheap imports.

To “save jobs,” the government at Home places a high tariff on all imported coconuts.

The immediate effect is to shield the inefficient domestic producers from foreign competition. They now have an enormous financial interest in keeping this tariff in place. So, they hire lobbyists to spend all day at the capital, arguing for the tariff’s importance. In response, consumer groups and efficient producers (who could be exporting) hire their own lobbyists to fight it.

In addition to keeping along inefficient producers along, a significant portion of the island’s talent is now engaged in a zero-sum political battle. These efforts don’t create a single new coconut; they are simply trying to influence policy. This is what economists call rent-seeking, and the resources spent on it are a complete deadweight loss to society. Tariffs are a primary driver of this wasteful activity because they create large, concentrated benefits for small, protected groups.

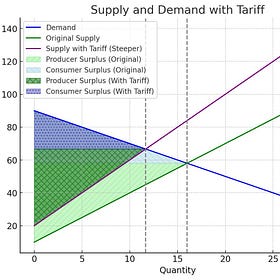

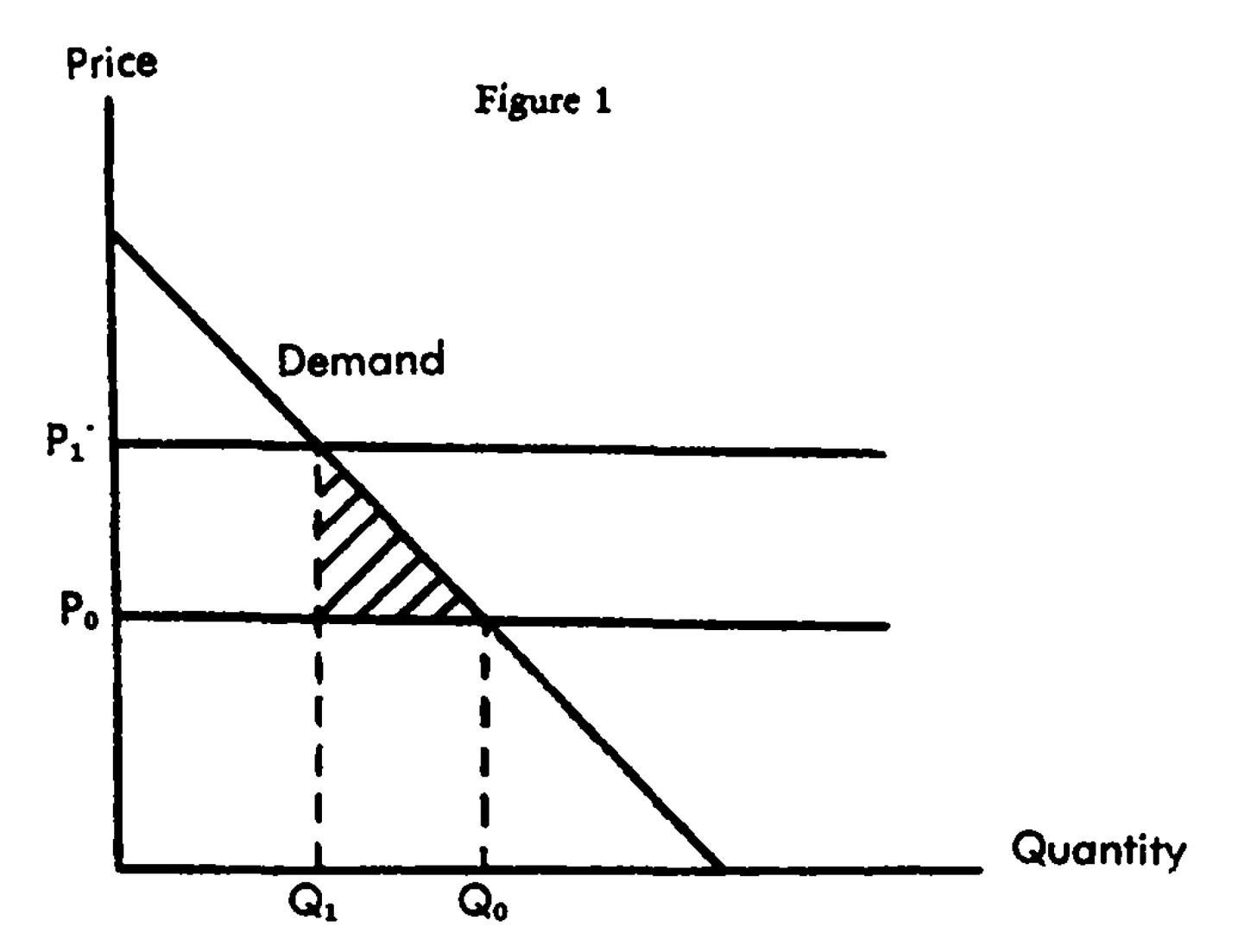

Tariffs were a key example in both OG rent-seekings papers, one from Gordon Tullock on “The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft” and one from Anne Krueger. The loss from the Tullock rectangle (from P_1 to P_0 out to Q_1) dominates the typical deadweight loss triangle.

In today’s world, this is even worse. We literally have Trump setting firm-by-firm tariff rates. This adds all of the rent-seeking costs, plus all the inefficiencies above, as you narrow the base to fewer and fewer companies.

The problems compound

Tariffs can seem appealing in theory, especially if no one changes their behavior. If people keep importing the same amount no matter the tariff, it’s an easy way to raise money. That’s part of why tariffs were so common historically: they’re relatively simple to administer and hard to evade. You collect them at the port, and that’s that. But that logic only works if behavior stays fixed. And if people don’t respond, it really doesn’t matter what you do. Economics is about how people change in response to prices. The moment consumers or producers start reacting to the price changes—as they always do—you’ve introduced distortions. As I wrote before,

The deadweight loss comes because tariffs push companies (and consumers) to change their behavior in ways that use up more real resources for the same outcome—building plants in suboptimal locations, reorganizing supply chains, and developing elaborate workarounds like seat removal. These distortions represent pure economic losses that benefit no one. It’s like forcing someone to take a longer route to work—the extra gas purchases help the gas station (although it hurts whatever you don’t spend money on). But extra time is simply a wasted resource; no one benefits. So even when tariffs “succeed” in moving production to the US, they create waste that goes beyond just higher prices.

Notice the pattern across all models above. Each additional layer of realism made them look worse:

Model 1: Tariffs distort consumption choices

Model 2: Tariffs distort both consumption and work decisions

Model 3: Tariffs attack productivity by taxing productive inputs

Model 4: Tariffs are bad at redistribution

Model 5: This extends to capital, making the entire economy less productive

Model 6: Tariffs create wasteful rent-seeking that diverts resources from productive activity

The logic runs deep. They cut against everything we’ve learned about good tax policy. They violate the most important results in optimal taxation: Diamond/Mirrlees, Atkinson/Stiglitz, Chamley/Judd. They shrink the pie before we can even tax it. And they open the door to all kinds of lobbying and rent-seeking.

It’s not that other taxes are perfect. It’s just that tariffs manage to break all of the principles of public finance at once. They can have other purposes related to defense and strategic trade policy, but this gives a sense of why economists react so strongly. It’s just a bad way to tax.

"the first endowment model"

WHAT "first endowment model?" I didn't notice it.

I’d propose a different reason economists have tariff derangement syndrome. It’s culturally coded as nationalist/racist/trump, and most economists are culturally the opposite.

I think that drives 99% of the reaction. The points you make are perhaps 1%.

I noticed this during COVID, when I watched nearly** every “libertarian” economist I know turn into a raging authoritarian that abandoned all cost benefit analysis or philosophical principals because their social class (urban professionals) had decided that that there was a culturally coded response and that was that. A lot of ink got spent rationalizing that response, but it was pretty transparent at the time and many can now look back on it with shame.

Personally, I find income taxes more distortionary than tariffs. Income taxes make me want to work and save less. I’ve responded to high income taxes in this way.

Tariffs basically work like a consumption tax. Cheap dollar store stuff is no longer a dollar, so I buy less of it. This really doesn’t have a big impact on me. Childcare is now cheaper (my income and their income is taxed less) so I consume more of it. Our families entire decision about whether to have a second income or not basically comes down to income taxes and childcare costs (childcare providers also pay income taxes).

In general I think my consumption basket (including work/leisure/saving) has improved under tariffs*. The same would is true of say an alcohol tax. Yes, it distorts my consumption of alcohol, but perhaps that’s a good thing.

I’m not convinced that the current exponentially growing trade deficit is a good thing. I won’t rehash it all in this comment, but I don’t think “borrow ever increasing amounts of money we can’t/aren’t going to pay back from financially repressed Asians so we can consume more” is a good long run pattern of specialization and trade.

*I speak of this pretty theoretically. At 1% or so of gdp, tariffs aren’t really changing anything at all. People are just going to pay the 15%, the impact on overall prices and income taxes rates will be practically zero. $300b a year? After twenty years maybe that will add up to two years of Covid deficits, lol.

The biggest change to my economic incentives was moving to Florida because it lowered my income taxes and gave me school vouchers, the combination of which greatly increased the post tax/expense value of my wife’s career. Go MAGA!

**you can of course find a few economists that signed things like the great barrington declaration. But I speak from observing the orange line libertarian economist class in general, let alone economists in general who tend to be left wing (think of Paul krugman as like a median avatar for your average phd economist).