An Equilibrium Perspective on AI

People always respond. Take that seriously.

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 7,500 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Many economists focus on people’s choices: Do people make rational choices? Which product does a consumer pick? What price does the monopolist set? Following Armen Alchian, I focus more on processes and feedback mechanisms: What is the feedback if people are wasting resources? How could people learn they are making “mistakes”?

Feedback is core to how markets operate and when they work well. Markets provide concise feedback that is more persuasive than any written argument. Did you make a profit? Great! You turned lower-value resources into higher-value resources and can stay in business. Did you fail to find suitable workers? Too bad. You aren’t offering a good enough package of wages, benefits, and amenities. Feedback is also crucial outside of markets. In academic work with Josh and Alex Salter, I argued that democracy works to the extent it provides political decision-makers with the appropriate feedback. Thomas Sowell’s Knowledge and Decisions is the most thorough exposition of the feedback perspective.

The form of feedback is what ultimately generates and sustains any equilibrium, and equilibrium is one of the core aspects of our brand of price theory. Anytime I approach a new area, I bring my Sowellian feedback-and-equilibrium eyeglasses.

With the release of ChatGPT and similar generative artificial intelligence (AI) models, everyone seems to be talking—well, everyone who is very online like me seems to be talking—about the future impact of these models. What happens when we reach artificial general intelligence or AGI?

For readers who are less online, lots of people are worried. Just this week, big names (and many fake names) signed a letter urging a 6-month pause on training AI systems. In Time Magazine, Eliezer Yudkowsky, the most prominent alarmist in these discussions, said we should bomb data centers to stop AI development. Okay. That’s one approach.

When considering the impact of AI on humanity's future, it's important to take equilibrium and feedback seriously. People respond. Policy responds. What does that mean for the future development of AI?

This newsletter will place a few ideas from the AI debates in terms of feedback and outline how the common perspective among AI crowds differs from how economists generally think about feedback.

Also, given the topic, I feel pressure (a form of feedback) to give my confidence level.

Confidence level about the value of the framework: High.

Confidence level about any specific AI predictions: Low.

Overall confidence level: Medium.

Commonly Discussed Feedback Mechanisms in the Future of AI

I want to differentiate between escalating and dampening feedback mechanisms. Escalating mechanisms reinforce some initial action while dampening mechanisms push against that action. Sometimes people talk about positive vs. negative feedback mechanisms, but that can be confusing with good and bad.

Much of the discussion around AI focuses on escalating mechanisms. The usual story around the danger of AI is that the models, by their construction, keep getting more and more powerful. One of the significant risks posed by AI is the potential for a "hard takeoff" scenario, in which an AI system rapidly becomes superintelligent and becomes able to improve itself at an exponential rate. In such a scenario, the AI system could quickly become vastly more intelligent than any human, and it is difficult to predict how it would behave or what its goals would be. What makes AI a unique danger to humanity, relative to historical dangers, is exactly this type of escalation. That is escalating feedback that turns out poorly.

But people who are extremely optimistic about AI also think about the escalating feedback of AI models. For example, Tom Davidson has an interesting report on “Could Advanced AI Drive Explosive Economic Growth?,” which “evaluates the likelihood of ‘explosive growth’, meaning > 30% annual growth of gross world product.” The report draws on a typical, escalating feedback loop that one sees in economic growth models:

more ideas → more output → more people → more ideas

That can then be translated into the framework of AI systems to have the following escalating system:

more ideas → more output → more AI systems → more ideas

He doesn’t argue that explosive growth is inevitable, just that it could happen through such an escalating mechanism. If it does occur, that is an escalating feedback mechanism that turns out wonderfully. 30% growth per year would be pretty neat.

Both sides, the optimists and the pessimists, are thinking about the escalating feedback.

Feedback Mechanisms in Economics

Economists often think about the dampening feedback mechanisms that could help to mitigate its effects. As always, the best place to start is supply and demand.

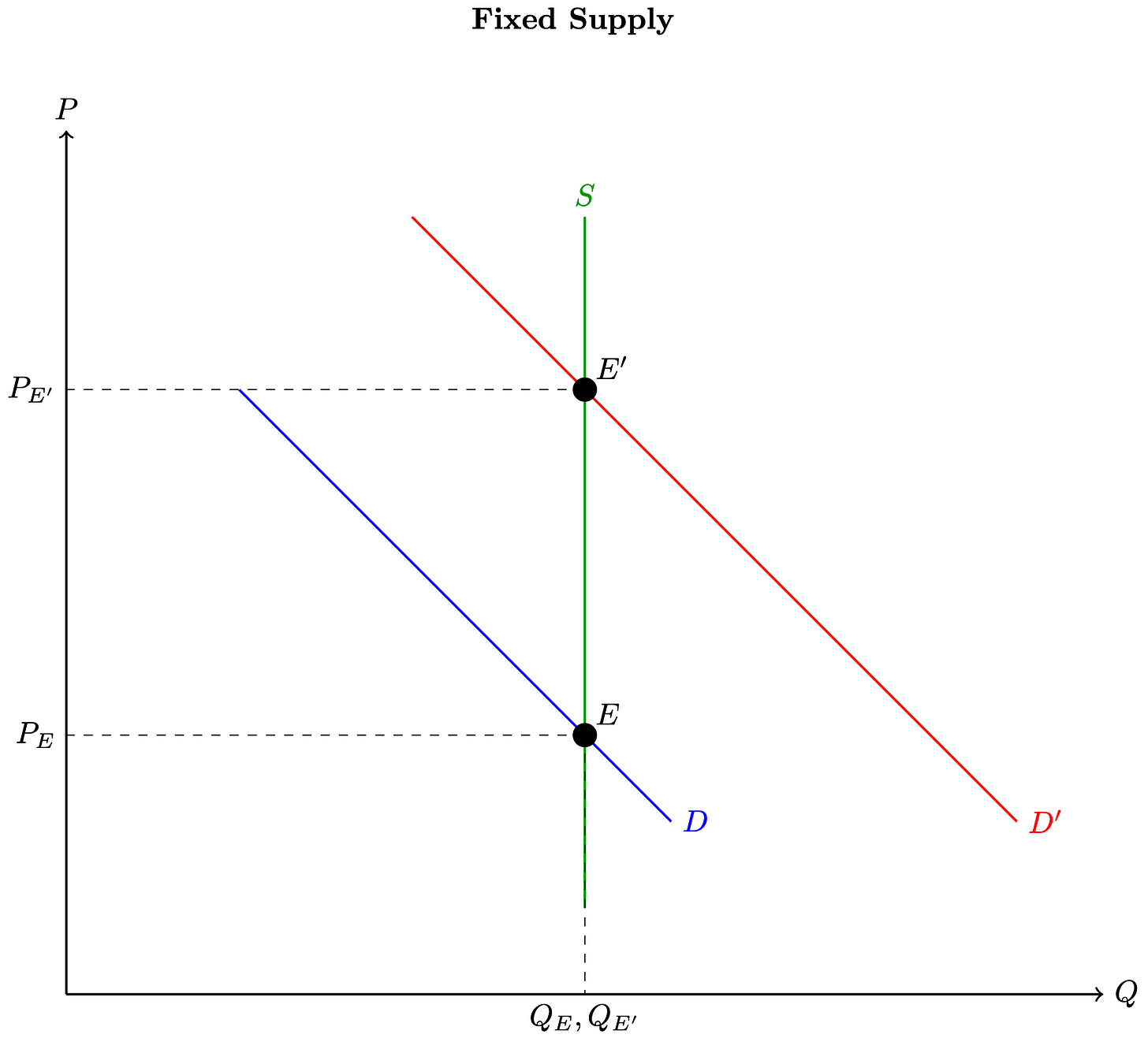

Supply and demand is a dampening mechanism. Suppose we have an increase in the demand for apples. If we ignore how other people respond, which is what many non-economists do, we will assume there is a fixed supply of apples in the world. With a fixed supply, the price may rise a lot. The graph is as follows.

But economists usually think that a key feature in any market is to consider how supply responds. When prices rise, suppliers bring more apples to the market. The quantity supplied increases, which chokes off the original price rise. In a world where we assume people (suppliers) can respond, the price increase is smaller than in a world where they do not respond. Again, we can plot this.

Given a long enough time horizon, many textbooks (not me) often assume the supply curve is horizontal. In that extreme case, the original demand curve has zero impact on prices. It is completely offset by the response of other people; the dampening feedback mechanism is 100% effective.

Dampening feedback is much more common than just supply and demand. It follows directly from “people respond to incentives” and “people adjust on the margin.” A bad thing happens (such as when a hurricane comes, so people need generators), and people take steps to reduce the costs of that bad thing (people bring generators to the area).

While super common in economics, dampening mechanisms aren’t everything. If supply is downward sloping, you no longer have a dampening mechanism but an escalating mechanism. In that case, increased demand drives down marginal cost, which increases the quantity supplied, which further increases the quantities demanded. If that’s the full model, this process goes on forever. This is how endogenous growth models work, like those discussed above. Technological progress begets progress. Otherwise, you have Solow growth which burns itself out and eventually stops.

But even standard endogenous growth models have a force that is dampening growth. The balance of dampening feedback and escalating feedback leads to growth, yes, but it doesn’t lead to higher and higher growth rates. Normally in growth models, growth steadies at 2%, not the 30% considered above.

The reason is that while ideas generating ideas is important for growth, it isn’t only the only mechanism at play. Ideas get harder to find.

Relevant to the AI debate, within machine learning, Tamy Besiroglu separates the “standing-on-the-shoulders” effect (progress now makes progress in the future easier) from the “standing-on-toes” effect (adding researchers today results in reduced productivity of other researchers). He estimates the “standing-on-toes” effect dominates, so research productivity declined by between 4% to 26% when the addition of new researchers. It is true, as Ben Southwood argues, “scientific slowdown is not inevitable.” But a slowdown is what we’ve seen in the past, so it is my baseline for what I will expect for the future.

For any outcome to be stable (even stable growth), it needs to have sufficient dampening forces that push it locally toward the equilibrium. That may be a shortcoming of the equilibrium point of view, but it is central to economic reasoning. Maybe that means we have a hard time explaining the change from zero growth to 2% experienced over the past 10,000 years. Maybe this is a truly radical change that we aren’t used to. But who’s better at explaining economic growth than economists?

How Will People Respond to AI Threats?

Let’s return now to the threat of AI and take seriously dampening feedback mechanisms that could help to ensure that its impact on society is not overwhelmingly negative.

It's worth looking at the existential risk of climate change as an example of how feedback mechanisms can work. There are both escalating and dampening feedback mechanisms at play. For example, as the ocean absorbs CO2 and warms, it becomes less able to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, which further warms the planet. As my friend Adway De’s dissertation fleshes out, this amplifies the costs of CO2 emissions relative to only looking at the CO2 levels in the atmosphere. That’s a feedback mechanism grounded in basic chemistry.

But that’s not the only feedback relevant to climate change. The economist will stress that people can also adapt by moving away from the ocean or changing the crops they grow. People respond to rising costs in such a way that lowers but doesn’t eliminate the ultimate harm. Matthew Kahn has done amazing work on climate change that takes the price theoretic ideas of feedback and equilibrium seriously. Check out his Substack posts like this one.

However, just as with supply and demand and climate change, there are potential equilibrium effects that could help mitigate the risks of a hard takeoff scenario. As Stefan Schubert pointed out, there will be an endogenous societal response.

One such effect is the development of “AI safety” research, which aims to ensure that AI systems are designed in a way that is safe, reliable, and aligned with human values. This type of research could help to ensure that AI systems are designed to avoid dangerous or harmful behaviors and to prioritize human safety and well-being. This is already happening. People are working on alignment, but not many, according to Leopold Aschenbrenner.

But in another post, Leopold argues alignment is doable and,

The wheels for this are already in motion. Remember how nobody paid any attention to AI 6 months ago, and now Bing chat/Sydney going awry is on the front page of the NYT, US senators are getting scared, and Yale econ professors are advocating $100B/year for AI safety? Well, imagine that, but 100x as we approach AGI.

I would stress that firms have strong incentives to regulate the AI associated with them. Microsoft—with its $2 trillion market cap—doesn’t want its AI system scaring reporters at the New York Times. This is why it’s good to have big brands with reputations to lose in the AI game. It’s not a perfect mechanism, but we can’t ignore it.

Beyond firms and market feedback, Leopold seems to be thinking in terms of regulation and how it responds, as it did with damage to the environment. It is very possible that we overcorrect and regulation is too strong, but it is another dampening effect that we will take seriously.

Which Way, Western Man?

Nothing I’ve written tells us whether there are too many or too few people working on AI safety. I’m not taking a stand on how effective these measures are or what policy should be; I’m merely stating that we need to think about this feedback when we want to make predictions and do cost-benefit analyses. For climate change and AI risk, the final outcome, whether it spirals out of control or stays stable, depends on which force is greater.

In fact, there is an internal contradiction if we take the dampening mechanism too seriously. In the case of supply and demand, if everyone thinks the price will just be unchanged, so there is no extra profit to be made, and no one has any incentive to increase supply. Similarly, if there is no risk to AI because of the feedback mechanisms I outline, no one has the incentive to take safety precautions.

Taking seriously dampening feedback mechanisms should give us pause on the most extreme predictions where the escalating feedback effect spirals out of control. In the 1960s and 1970s, people were right to be worried about the environment. But the more dire predictions turned out to be false because they ignored feedback mechanisms. Supply responds to increased demand for minerals; environmentalist Paul Ehrlich lost his famous bet to economist Julian Simon. In places like the United States, policy responded as well, and air quality improved. There are challenges ahead, and I’m glad people are working on environmental issues and AI Safety.

But I guess I’m not ready to bomb data centers just yet 🤷♂️.

A recent example of this could be the "European are going to freeze over the winter because of gas prices" prediction that doomsayers gave when Ukraine was invaded. Dampening mechanisms at every level were set in motion very quickly (e.g. new gas supply sources, households accumulating wood).

Just discovered your blog. I very much like the economic perspective on the AI doomers. We need more of that (Robin Hanson is one of the other few). It's distressing how some people (including Yudkowsky and Bostrom) have gone from being pro-tech to being technology doomers. JUST as AI is starting to look useful, lots of people are trying to stop it!