Common Chicanery about Competition

Don't believe these misconceptions about supply and demand

Over my next few newsletters, I plan on digging more into the details of our favorite model, good ol’ supply and demand. Shocker. I know.

Before doing that, I want to make sure we are on the same page about what the baseline model actually says. In particular, I want to quickly go through three myths/fallacies/willful-misreadings-for-someone’s-political-goals about what is going on in the competitive model.

I want to dispel some of the chicanery, which means (as I just learned from my dictionary) “deception by artful subterfuge or sophistry.” So you learned one thing in this newsletter at least.

As we will see, most of the time, these misconceptions, besides that chicanery, are reasonable and likely come from some simplifying assumptions that make life easier when explaining the model to undergrads. But, dear readers of Economic Forces, you have revealed your preference for learning more than just the simplest understanding of economics. That’s why I’m here: to help us move beyond the basics about the basics.

And I don’t care what your favorite textbook says. Anyone can make some assumptions and call it “the competitive model” if they want. I simply want to clarify what I am assuming when I draw supply and demand and talk about the price/quantity/shifting curves/etc. You know, econ stuff. What do I actually need to assume for that model to make sense? As we will see, most people bring in too much extra baggage into the discussion. You should not.

Competition Does Not Require Complete Knowledge

When I draw supply and demand, I am not assuming that the buyers and sellers know everything and have complete information about the economy. All I need to assume is that:

buyers know their own preferences,

sellers know their own production capabilities, and

buyers and sellers know the market price.

It’s often reasonable to assume I know my preferences as a buyer. Then I only need to know the price of a good. That’s a heck of a lot less than “everything.” To use the famous example from Hayek, one remarkable feature of markets is that when the price of tin increases,

All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere.

Contrary to naive claims about complete information, the competitive market functions with minimal information. Any other mechanism would require people to know more than they need to know with competitive markets, aka supply and demand.

These aren’t just some fluffy words from Hayek. This is a theorem and a thoroughly studied one. I give all the references and explain this in the intro of a working paper with Rafael Guthmann.

But what about asymmetric information?! Something, something, something, Joseph Stiglitz!

Sorry. No theorem says markets stop being competitive when information is asymmetric. Sure, there are cases where asymmetric information disrupts the competitive market, such as when you know the quality of a car that you’re selling and I do not. But, as the Hayek quote highlights, competitive markets can work just fine when people don’t have all the information.

Competition Does Not Mean Zero Profits

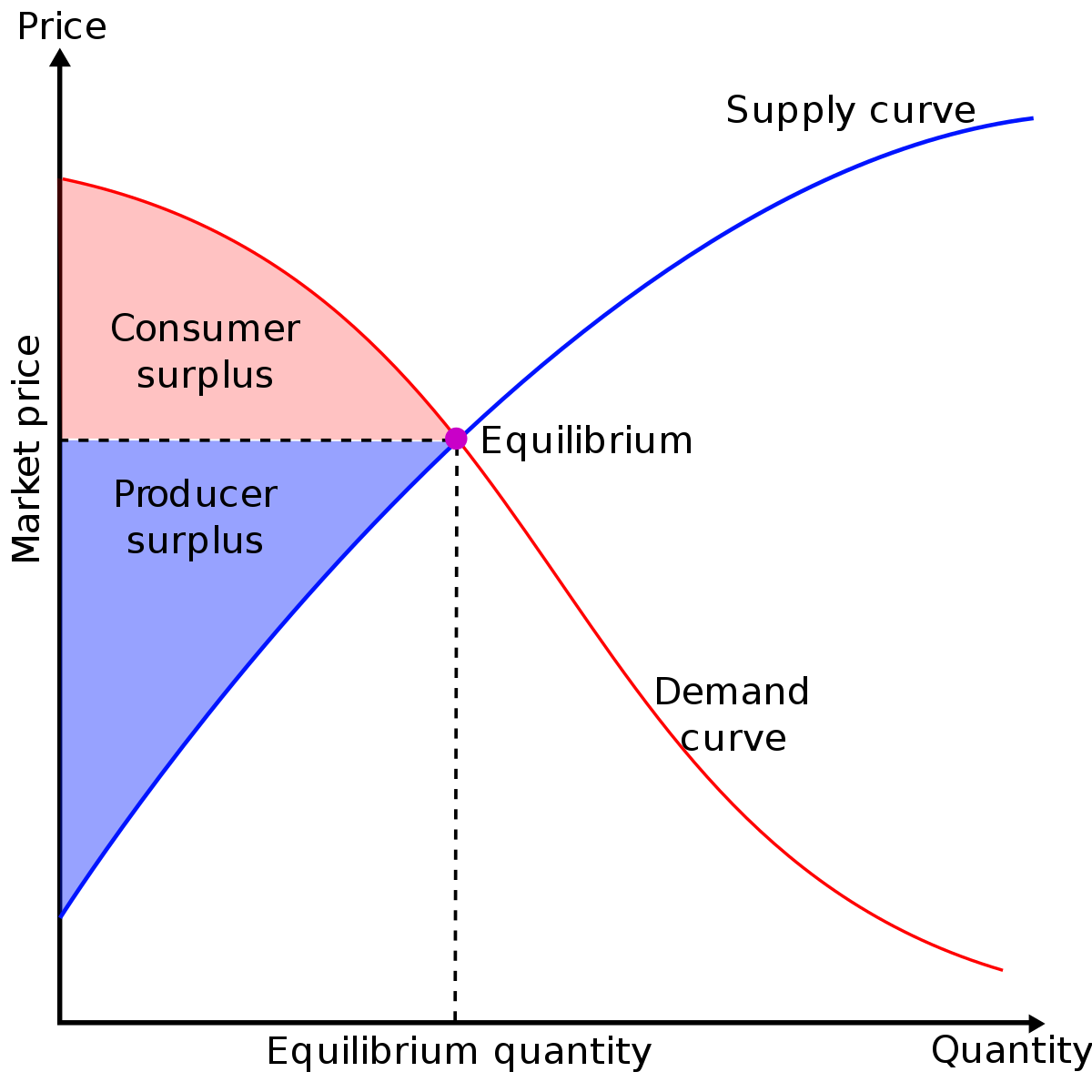

This one should be obvious. Draw supply and demand. There is an area between the market price and the supply curve (which comes from marginal costs). When the price is above cost, I’d call that profit. You call it what you may. It’s not zero.

The misconception above about information is one reason people have misconceptions about profits. Their logic goes: if people have complete knowledge, then all suppliers would know the same ways of producing goods, then all suppliers would use the lowest cost technology available, then profits would be zero.

But why assume all suppliers know how to produce the same goods at the same cost? We don’t need that assumption! I allow people to have different preferences. Why not allow them to have different costs?

To see the parallel, remember that we can think of preferences in terms of “household production function.” It’s not that the consumers on the left side of the demand curve inherently have a stronger “preference” for tofu. Instead, we can think of them as having more knowledge or lower production costs to turn tofu that they buy on the market into tasty meals, which is what actually gives them utility. The two representations (preferences and technologies) are the same.

I allow consumers to have different preferences/technologies. Why not give suppliers the same ability? Why restrict ourselves to only study markets where everyone knows the exact same production techniques? It’s silly to handcuff yourself like that.

Now there may be reasons to believe that in a dynamic model people will learn how other people are producing at a lower cost. We can write down a model where everyone would eventually start using the lowest cost technology.

This learning may be one reason to suppose that in the long-run the supply curve is flatter and more elastic. But just as no one takes the Second Law of Demand and infers that demand curves are perfectly elastic, there’s no reason to assume that supply needs to be perfectly elastic, even in the long-run.

With an upward-sloping supply curve, there is a gap between price and marginal cost. Call them profits. Call them rents. Whatever you want. They are perfectly compatible with competition, even in the long run!

Competition Does Not Require an Infinite Number of Buyers and Sellers

Surely, the story goes, without an infinite number of buyers and sellers, any individual can change the price, and therefore the market isn’t competitive.

Any economist who has taken microeconomics beyond principles has surely seen a competitive model with just three(!) players: two sellers and one buyer. I’m talking about the standard Bertrand duopoly model.

What do I mean when I say that Bertrand competition is competitive? I mean, that if we draw the supply and demand curves for the economy and everyone is assumed to be a price-taker, the outcome in terms of prices/quantities/etc will be the same as the more complex model that people teach under the heading of “Bertrand competition.”

Competition depends on how close of substitutes there are. With a standard Bertrand model, each seller is a perfect substitute for the other, as far as the monopoly buyer is concerned. Therefore, neither seller has any bargaining power, despite there only being two sellers. That perfect substitutability gives perfect competition.

Beyond the standard Bertrand model, two buyers and two sellers are often enough to ensure perfect competition (if both sides are free to offer whatever price they want).

This does not mean that the size of the economy is irrelevant. In a large economy, each seller is more likely to have a close substitute/competitor and so a large economy is more likely to be competitive. But many buyers and sellers are not necessary for competition.

In fact, while we are at it, large numbers are not even sufficient for competition. As Edgeworth originally pointed out, in a large matching market, any particular person may still have substantial bargaining power. 🤯 For anyone who wants the technical details on this, read Gretzky, Ostroy, and Zame.

Keeping these details straight matters; people will try to invoke these assumptions to dismiss supply and demand. “This market doesn’t have complete information. It’s not competitive!” We’ve all seen the act. Chicanery.

And these subtleties are not just fun, theoretical speculation. It’s what the experimental evidence tells us as well. Vernon Smith, a winner of the very real Nobel Prize in Economics, ran early experiments that show how competitive markets arise, even with few players who only know their valuations and can choose their own prices. This went against the common belief at the time. Unfortunately, it’s still a common belief 60 years later.

Also, in a disgustingly-under-appreciated experiment, Dan Friedman and Joseph Ostroy even construct the “worst-case” scenario for competition that gave players lots of market power to try to exploit. Still, when people choose their prices and quantities to offer for trade, the market becomes competitive. When people can’t freely choose prices (looking at you, price fixers), the market is less likely to be competitive in the supply and demand sense.

People often complain about the problem of taking Econ 101 and then using those models (with such strong assumptions!) to study the world. I agree. So let’s not act like supply and demand needs those stupid assumptions.

Drop unnecessary assumptions. Don’t drop supply and demand.

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!R9wX!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fce3016db-4a24-4684-be3f-d24cb2104041_480x480.gif)

Great piece, Brian.

Even though I agree with part regarding asymmetric information, I'm wondering if asymmetric information could come to trouble, especially in healthcare sector. Or should it be called "asymmetric chance" since patients have much less chance to prepare for health-related events, even more so in an accident. I believe you've heard this question a lot from your students but it'll reall help if you could enlighten me a bit. Thanks in advance!

I agree with one of your conclusions, but I disagree with your proof. So I want to quibble a little.

You say that profits can exist under perfect competition because of the existence of producer surplus. But producer surplus is really profit over marginal/variable costs, ignoring fixed costs.

Producer surplus is the difference between the market price and the price the firm would have accepted. In the short-run, the firm will accept any price that is greater than its variable costs, even if it fails to cover its fixed costs. So the existence of producer surplus may merely indicate that firms are covering their variable costs, not that they are making profits (i.e. revenue exceeds total costs).

However, we can still prove your proposition in another way, by using the firm side rather than the market side. I.e., draw the perfectly competitive firm's graph, with horizontal P=MR, upward-sloping MC curve, and U-shaped ATC curve. The marginal firm will have P=ATC and make zero profits. But other firms producing an identical product at lower costs will earn the same P=MR but have a lower ATC, creating profits (P>ATC). Thus, the marginal firm makes zero profits, but all infra-marginal firms will make positive profits.

In my Econ 101 course, I use the example of growing avocadoes in Alaska. If the demand curve for avocadoes shifts right on the market side, then the P of avocadoes increases. All avocado farmers temporarily earn profits. In the long-run, supply increases, and the price falls back down until their profits disappear.* But here is where I make the next distinction: suppose that the way we increased the supply of avocadoes was by building greenhouses in Alaska. This clearly costs more than growing avocadoes using sunlight in California. So the Californian farmers will earn Ricardian rents. The marginal Alaskan farmer will earn zero profit because Alaskan avocado farmers will build greenhouses up until the point where the last greenhouse earns zero profit. But at that point, Californian avocado farmers are selling identical avocadoes with a lower ATC because of the free sun and warmth of California. So the marginal Alaskan avocado farmer earns zero profit, while the Californian avocado farmers all earn Ricardian rents.

I tell my students that the reason why profit disappears is that profit creates an incentive for competitive entry. If all firms are identical, then they all compete the price down to the cost of production. But if firms are not identical, then instead, firms enter until the last firm earns zero profit. Prior firms with lower costs will be earning profits. But the final firm that enters will earn zero profits, and no one else enters after that.

* (Aside: if it a constant-cost industry, then the long-run supply is perfectly elastic and price falls back down to its original level. If increasing-cost, then the long-run supply is upward-sloping - but more elastic than short-run supply - and the price falls back down only partway towards the original price. But either way, if all avocado farmers are identical, then in the end, all profits return to zero. Identical firms plus increasing-cost implies that costs for all firms increased identically. Perhaps increasing the supply of avocadoes caused an increase in the demand for fertilizer, so fertilizer prices increased equally for all farmers.)