Contestability matters more than concentration

Antitrust implications of the 2025 Nobel

We will be done with Nobel pieces soon, but one more!

This week’s newsletter is an expanded version of a post that originally appeared on Truth on the Market, a website full of scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more.

The 2025 Economics Nobel went to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for exploring innovation-driven economic growth. I already wrote a general explainer about the prize.

Here I want to make a different claim: If you work in antitrust, you should pay particular attention to their scholarship. Their work, especially that of Aghion and Howitt, fundamentally changes how we think about competition in markets.

The standard antitrust framework inherited from 1960s industrial organization focuses on market structure. Count the firms. Measure concentration. Assume that structure determines conduct, which determines performance. More firms mean more competition, which means lower prices and better outcomes. The U.S. Merger Guidelines embody this view with their use of Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) thresholds.

The Aghion-Howitt framework tells a different story. Competition is a process of innovation and displacement. Firms compete by trying to make better products, not just by cutting prices on existing ones. What matters is not the number of firms at any point in time, but whether new innovators can challenge incumbents. Market structure is an outcome of this competitive process, not just a cause of competitive behavior.

Let me walk through what Aghion and Howitt’s work actually says and what it means for how we think about competition policy.

Competition as Creative Destruction

The key paper from Aghion and Howitt is their “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction.” The paper starts with a pure theory question. Endogenous-growth papers in the late 1980s from the likes of Paul Romer and Robert Lucas made knowledge accumulation drive long-run growth, but typically via horizontal variety or learning without obsolescence.

The Nobel Committee starts with something more important: a puzzle about the world.

Advanced economies show smooth, steady growth in GDP—roughly 2% per year in the United States for decades. Yet underneath that smooth aggregate, the micro-level economy is turbulent. In the last quarter of 2024 alone, the U.S. economy created 8 million jobs, while simultaneously destroying 7 million jobs. How do we get smooth growth from such messy dynamics?

Aghion and Howitt’s answer: innovations arrive across many sectors. In any single sector, you see sudden jumps when breakthroughs happen. Netflix enters and Blockbuster collapses essentially overnight. The iPhone launches and BlackBerry’s market share disappears. Creative destruction is violent and discontinuous in any given market.

But the economy has thousands of sectors. At any moment, some sectors experience breakthroughs, while others remain stable. The jumps don’t happen simultaneously. They’re staggered, random, and uncorrelated. Across thousands of sectors, those jumps average out. Aggregate growth becomes steady. This reconciles the two perspectives we see in the data. Smooth macro growth. Turbulent micro dynamics. Both are real. Both are essential.

For antitrust, the important part is that the model makes innovation endogenous. Firms invest in R&D in hopes of winning the next innovation and enjoying a monopoly. The monopoly profit is the carrot. But other firms keep innovating, too, so the monopoly is temporary. Eventually, someone else’s innovation displaces you. That’s the stick.

Something that will not sit well with people who see the world through an antitrust lens is that growth comes via serial monopoly—firms take turns being monopolists as each innovation displaces the last. The monopoly profit motivates R&D investment. But the threat of displacement keeps firms innovating. No firm’s monopoly is permanent.

What This Means for How We Think About Competition

The Aghion-Howitt framework suggests we should think about competition differently than standard industrial-organization models do.

First, market structure is endogenous. Concentration doesn’t just fall from the sky. It’s an outcome of competitive processes. Maybe an industry is concentrated because one firm innovated successfully and grew large. Or maybe concentration reflects barriers to entry that prevent new innovators. The concentration measure alone doesn’t tell us which story is true. In fact, competition often increases concentration.

This matters, because the policy response differs. In the first case, the concentration came from competition—from a firm winning by innovating. Breaking up that firm might reduce the incentives for innovation. In the second case, the concentration came from blocked competition. Antitrust intervention might help.

We need to look at the process that generated the structure, not just the structure itself. Aghion and Howitt aren’t the only ones to point this out. It goes back to Harold Demsetz. But they are the ones to show this is the key fact of economic growth. This is the big deal.

Second, profits and markups can signal innovation, rather than market power. In the Aghion-Howitt model, successful innovators earn high profits. That’s the point. The profit is the reward for innovating, and the promise of profit motivates R&D investment.

Standard antitrust analysis treats high profits as presumptive evidence of market power that should be disciplined. But if those profits came from innovation, they’re part of a healthy competitive process. They provide the incentive for the next round of innovation.

This doesn’t mean all high profits are fine. Some come from barriers to entry or exclusionary conduct, rather than innovation. But we cannot just look at the profit level. We need to ask: where did it come from? Is this firm still facing threats from potential innovators?

Third, competition is about reallocation, not just outcomes at a point in time. Economists often measure competition by looking at whether prices equal marginal cost, whether there’s deadweight loss, and whether resources are allocated efficiently given current technology.

But growth comes from resources reallocating to more productive uses. The Aghion-Howitt model makes this explicit: The displacement of old firms by new ones is what drives productivity growth. More dynamic industries (those with higher rates of turnover) exhibit faster productivity growth. A significant portion of total productivity gains comes from this reallocation effect.

Pay Attention to Dynamism

This brings us to what I want to emphasize: business dynamism is not just a side effect of economic growth. It is economic growth, at least a big part of it. If we care about consumer welfare, we need to understand dynamism.

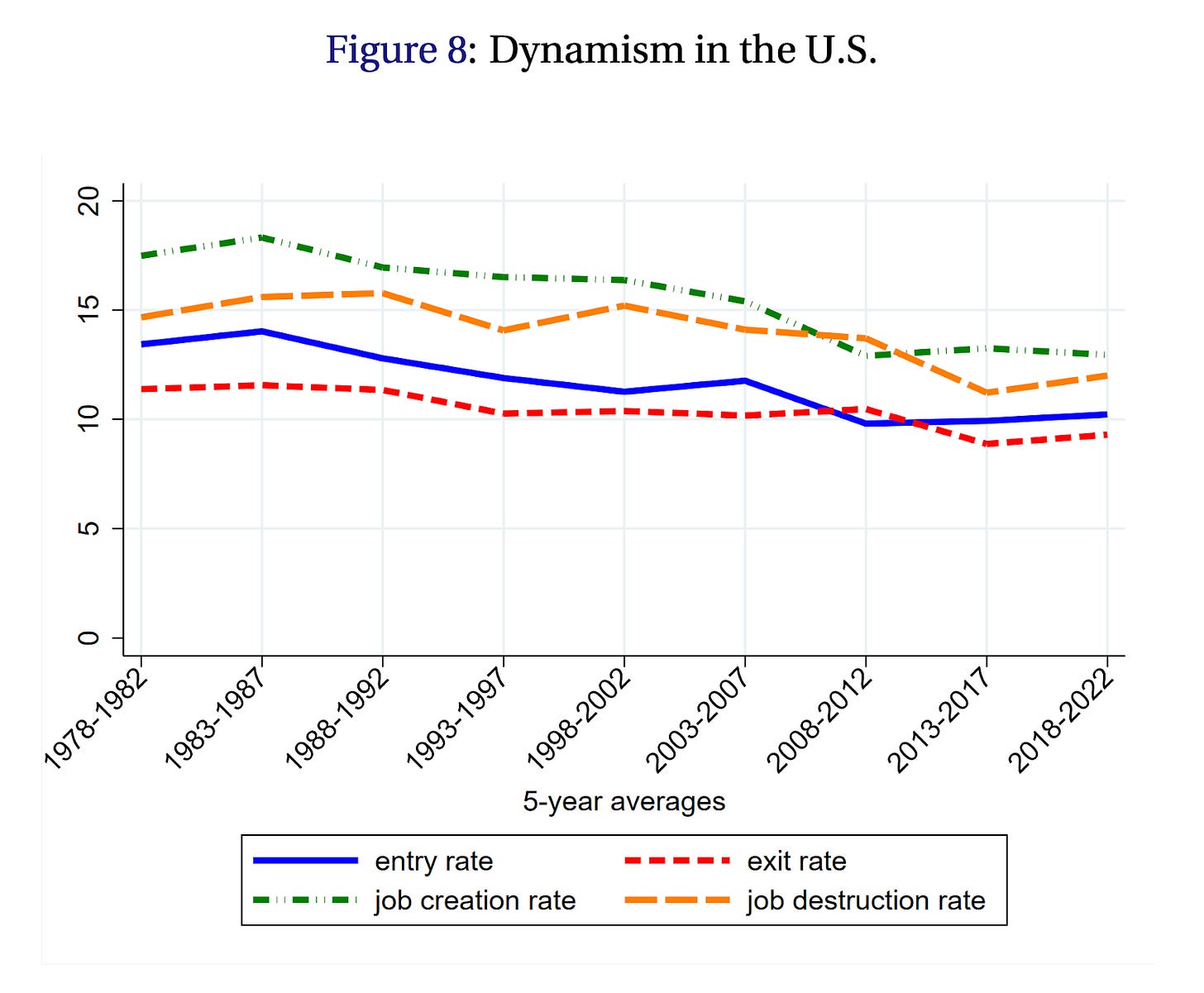

Start with the basic facts. The Business Dynamics Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau demonstrate that, in a typical recent year, about 10% of establishments will close and another 10% will open. The job-creation rate hovers around 15% of total employment. The job-destruction rate is similar. Every five years, roughly half of all jobs turn over.

Figure from Nobel Committee’s Scientific Background

Ryan Decker and co-authors documented that this dynamism was even higher in the 1980s and 1990s. These numbers were falling before the pandemic but are still crazy high. The smoothness in aggregate growth existed alongside even wilder churn at the micro level.

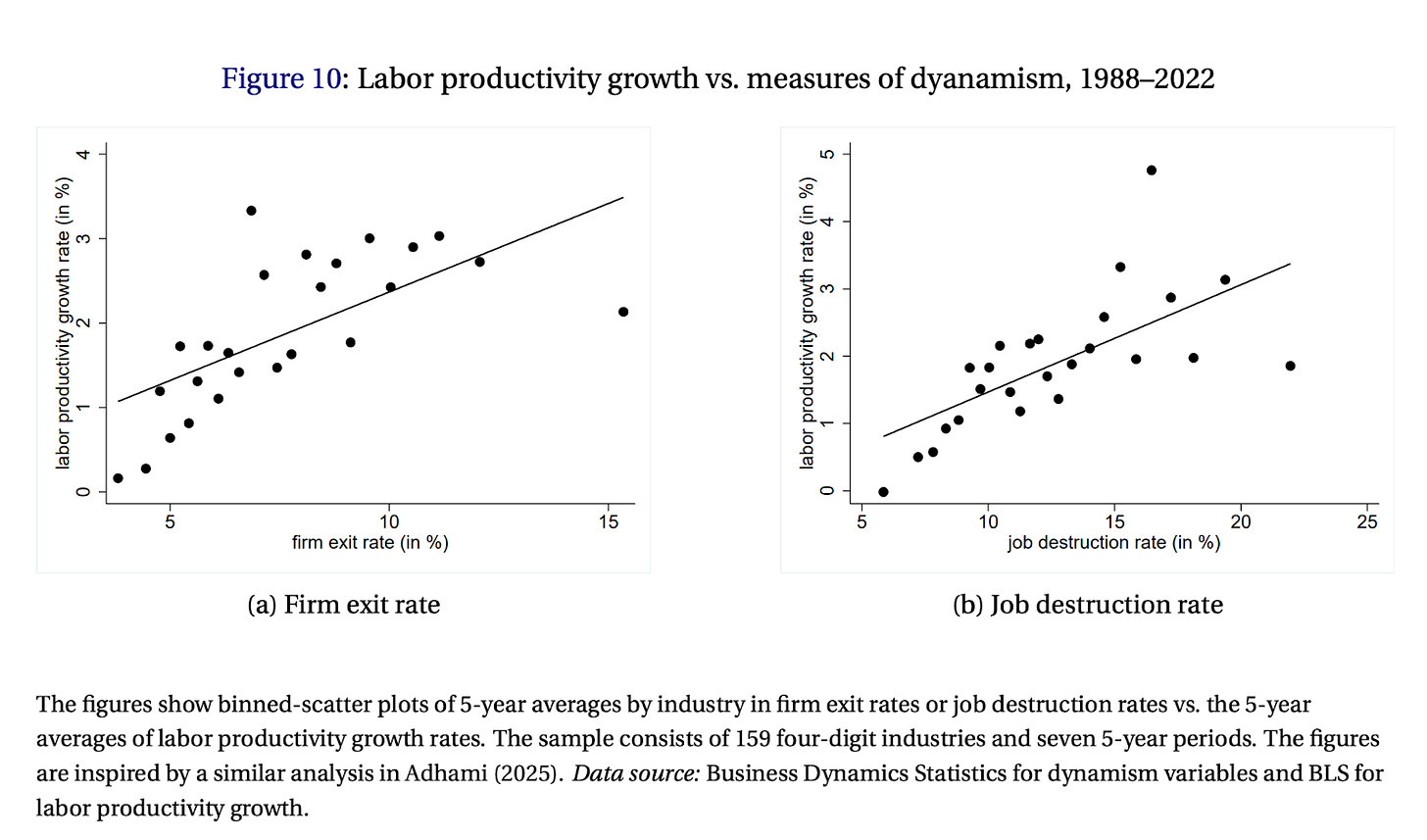

Industries with more churn—that is, more firms exiting and more jobs being destroyed—show higher productivity growth.

Figure from Nobel Committee’s Scientific Background

This is a huge part of economic growth. There are different decompositions, but David Baqaee and Emmanuel Farhi (2020) find about half of aggregate U.S. total-factor-productivity growth over the 1997–2015 period was due to the reallocation of production factors from low- to high-revenue-productivity firms. The scientific material shows this at an industry level.

Think about what this means. Firms constantly enter and exit. Workers move between employers. Products get launched and discontinued. The labor market churns. This isn’t a bug in the economic system. It’s a feature.

The reason is simple: not all firms are equally productive. In manufacturing, the 90th percentile plant is about twice as productive as the 10th percentile plant within the same narrowly defined industry. We aren’t comparing steel mills to bakeries; this is variation within essentially identical product markets. And this productivity dispersion exists in every sector we’ve measured.

The mechanism makes sense. Creative destruction reallocates resources. New firms with better ideas enter. Old firms with outdated methods exit. Workers and capital flow to where they’re most productive. This process drives aggregate productivity growth.

The Aghion-Howitt model captures this formally. In their framework, each innovation makes the previous generation obsolete. The old monopolist loses its position. The new innovator takes over. Resources reallocate. Productivity jumps. The threat of displacement provides the stick that keeps everyone innovating.

Without exit and displacement, you get stagnation.

How Should We Change Antitrust?

Several implications follow from taking the Aghion-Howitt view of competition seriously.

First, we should focus on maintaining contestability, not on structural thresholds. At the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE), we constantly argue against structural thresholds. Instead, Aghion and Howitt tell us that the key question is whether potential innovators can challenge incumbents. Can new firms enter with better products? Can today’s market leaders be displaced if they stop innovating?

(Important side note: This is quite different than whether they are being displaced. That version of “contestability” is what underlies the EU’s DMA, which has “fairness and contestability” as its primary objectives. But it’s not the same as the economic concept that derives from Aghion-Hewett, developed most fully by William Baumol, John Panzar, and Robert Willig in their book “Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure.” For an extended discussion on the differences between the two (and the considerable problems with the DMA version), see my colleagues’ paper “Regulate for What: A Closer Look at the Rationale and Goals of Digital Competition Regulation.”)

Maintaining contestability means antitrust should target conduct that blocks entry or insulates incumbents from competitive threats. These are barriers that may prevent the creative-destruction process from working.

It also means we should be cautious about bright-line structural rules. An industry might have high concentration because the most innovative firm won and grew large. Forced deconcentration in that case might reduce the incentives for innovation, without increasing actual competition.

What matters is whether the concentrated firm still faces competitive pressure from potential entrants. That requires case-by-case analysis, not mechanical application of HHI thresholds.

Moreover, we need to distinguish temporary monopolies that arise due to innovation from entrenched monopolies protected by barriers to entry. Aghion-Howitt models feature serial monopoly: firms take turns. The monopoly profit motivates innovation, but the threat of displacement keeps firms innovating. That’s very different from a durable monopoly protected by barriers to entry. A monopolist that faces no threats can coast. It doesn’t need to keep innovating.

For antitrust, we should ask: is this a temporary monopoly that resulted from innovation and remains subject to potential displacement? Or is it an entrenched monopoly protected by barriers? The answer depends on more than just duration. A firm might have high market share for years because it keeps innovating faster than rivals. That’s a serial monopoly, even if the same firm keeps winning. What matters is whether the firm faces real competitive threats that force continued innovation.

The best innovator can keep winning repeatedly. Google has led search for two decades. Microsoft has led operating systems for even longer. Amazon has led e-commerce since its early days. Does this persistence mean competition isn’t working? Not necessarily.

The competitive process doesn’t require that we observe turnover in market leadership. It requires that leadership positions remain contestable. A firm might maintain dominance precisely because it keeps innovating to stay ahead of potential challengers. Google didn’t just build a good search engine in 1998 and coast. It continuously improved search quality, added features, and invested billions in infrastructure. Microsoft kept updating Windows and Office, even as it has faced threats from open-source alternatives and cloud computing.

This means we can’t use “did the market leader change?” as a simple test for whether competition is working in any particular industry. We need to look at whether the incumbent still faces competitive pressure. Is it investing in R&D? Are its products improving? Are there credible potential entrants that could displace it if it stopped innovating?

But here’s the connection to dynamism: even though we can’t require turnover in every market, we should see high dynamism in aggregate. The economy has thousands of industries. In some, the best firm might keep winning. In others, new entrants will displace incumbents. What matters for growth is that, across all these industries, resources keep reallocating to more productive uses.

The aggregate entry, exit, and job-reallocation rates tell us whether this process is working economywide. When Baqaee and Farhi find that half of all productivity growth comes from reallocation, they’re measuring an average effect across many industries. Some industries might show little turnover. Others show lots. The average captures whether the creative-destruction process is functioning.

I admit there is tension here regarding antitrust enforcement. Traditional antitrust operates industry-by-industry, case-by-case. The U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) will challenge a specific merger in a defined market. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) will bring a monopolization case against a particular firm in a particular industry.

Here’s why this matters: Suppose we examine the retail industry. Department stores show declining entry rates and rising concentration. But maybe that’s because e-commerce displaced them—i.e., creative destruction working as it should. Now examine e-commerce. Amazon has a large market share in online retail, but Shopify, Walmart, and TikTok Shop are growing.

Taking a step away from antitrust to broader policy questions, however, declining business dynamism should concern us—but not for the reasons many assume.

For a while, the conventional wisdom treated macro trends as obvious evidence of antitrust failure. Declining startup rates? Must be rising barriers to entry from dominant firms. Falling job reallocation? Must be weakening competition. Rising concentration? Must be inadequate enforcement. The logic seemed straightforward: bad aggregate outcomes point to bad antitrust policy. This approach treats the problem as straightforward: if we see bad aggregate outcomes, we need more vigorous application of the traditional Econ 101 toolkit.

But Aghion-Howitt shows those simple models miss what actually drives growth. Competition isn’t about hitting the right HHI number or maintaining a certain firm count. It’s about the innovation and displacement process—whether potential entrants can credibly threaten incumbents, whether profits fund the next round of R&D, whether resources reallocate to more productive uses. The standard Econ 101 framework that focuses on market structure and static price competition can’t capture these dynamics.

This doesn’t mean declining dynamism is fine or that antitrust policy is irrelevant. It means we need to think more carefully about mechanisms. Maybe something is blocking the creative-destruction process, but we can’t identify what it is by mechanically applying concentration thresholds or presuming that high profits equal market power. We need to ask different questions.

The aggregate decline suggests something systematic is changing. Maybe barriers to entry are rising across many industries. Maybe incumbent advantages are strengthening. Maybe the threat of displacement is weakening.

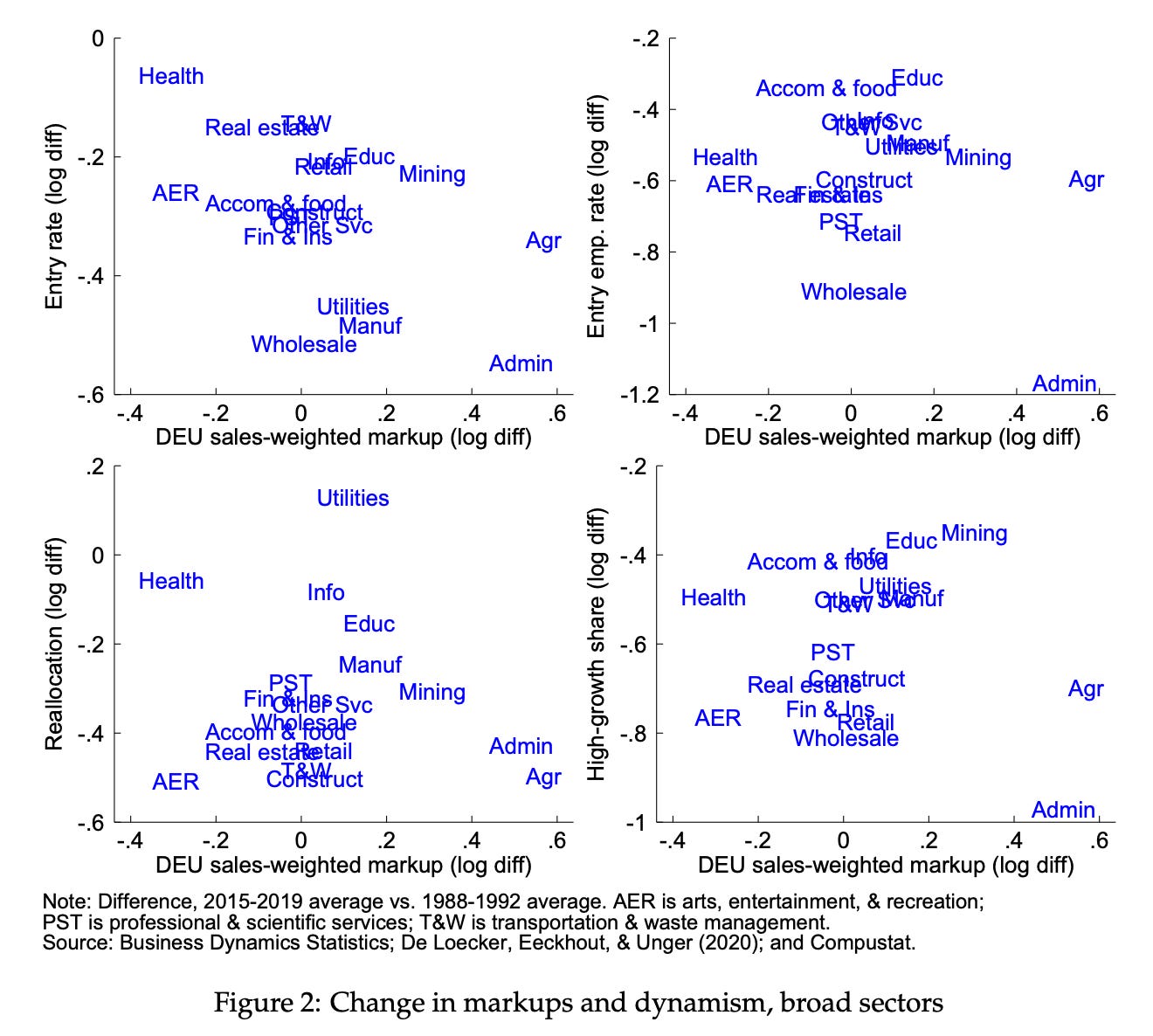

But maybe the dynamism decline is something completely unrelated to antitrust and market power. My research with Ryan Decker suggests this to be the case, since the industries that saw falling dynamism were uncorrelated with the industries that saw rising market power. Looking quickly, by industry, at how markups have changed (x axis) and business dynamism changed (y axis), there isn’t a systematic relationship.

Disentangling these explanations is hard. But the trend is worrying enough that we should be asking whether competition policy contributes.

Have we been too lenient on acquisitions of potential competitors? Have we underweighted innovation in merger reviews? Have we been too tolerant of conduct that raises barriers to entry? These are the questions that should animate antitrust policy.

But we need the Aghion-Howitt framework, not structure-conduct-performance, to answer them. The Nobel Committee got this one right.

Ideas vs. authors

Since I wrote my post last week, I’ve seen people point to Aghion and Howitt’s prize as validation for more aggressive antitrust enforcement. I’m not sure that is the right takeaway, but it could be. My post above isn’t really about stronger or weaker enforcement, although I understand why people would read it as calling for weaker enforcement.

The more important thing—that I’m urging above—is to think through the mechanisms. Not that no one in antitrust does; many do take dynamic competition seriously. Antitrust isn’t all about concentration metrics. That’s been a good change. But it is still centered too much, in my opinion.

The beauty of economic models is that once formalized, they truly become independent of their creators. We don’t need to genuflect to authorities or parse their every utterance to understand what their frameworks tell us. The Aghion-Howitt model of creative destruction exists as a mathematical object with specific assumptions, mechanisms, and implications. We can work through the logic ourselves.

The beauty of data is that we can do the same thing. We can assess the evidence one way or another. We can test those implications.

When someone claims “Aghion says X” as if that settles a debate, they’re confusing the person with the idea. The model speaks for itself through its equations and equilibrium conditions. If the model implies that serial monopoly drives innovation through creative destruction, that’s what it implies—regardless of what Aghion might say in an interview about AI policy or what his personal preferences might be.

I tend to disagree with Aghion and Howitt’s reading on policy. For example, Aghion and Howitt have a short 2022 paper that claims that superstar firms are responsible for the U.S. productivity slowdown. But I think they interpret the facts and the mapping to their theories (not just the 1992 paper) wrong. Maybe I’m wrong, but their argument rests heavily on the De Loecker, Eeckhout, and Unger (DEU) markup estimates. I’ve written why this evidence isn’t very compelling.

More importantly, their story about superstar firms blocking innovation contradicts the industry-level evidence. As I said, my work with Ryan Decker found no correlation between industries that saw rising markups and those that experienced declining business dynamism. If superstar firms were using their market power to suppress creative destruction, we should see this pattern consistently across industries. We don’t find that.

Aghion and Howitt didn’t know this fact in 2022. Hopefully, they do today (he lies to himself). At the same time, they know lots of facts that I don’t know, so don’t just trust me because I say so either. It’s just as likely that I’m putting too much weight on my own research. Sue me.

The Nobel Prize rightly recognizes brilliant contributions to our understanding of growth and innovation. But those contributions are tools for thinking, not answers carved in stone. We honor that work best by using those tools rigorously, testing predictions against evidence, and following the data even when it contradicts our priors. Whether that leads to more or less antitrust enforcement should depend on what we find, not on what we hoped to find.

While Professors Aghion and Howitt are evidently smart guys, it is Joseph Schumpeter who should have won the Nobel Prize, which he never did in his lifetime. Their work seems entirely derivative of Schumpeter's and not at all original. Even though they stole Schumpeter's "big idea" for their title, they do not seem to have given Schumpeter much credit (I infer this because you do not mention the master in your post.)

Almost a century ago, on page 95 of his deeply prophetic masterpiece "Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy" Schumpeter wrote, "The important thing is not the number of firms competing in an industry, but the ease with which competitor firms can enter the industry."

For anyone interested, here is an annotated outline of "CSD."

https://charles72f.substack.com/p/schumpeter-in-a-nutshell

Below is one of Schumpeter’s most profound insights. It could only have been perceived by that rare economist who actually understood business, not by a pure academic,

"Competition acts even when it is merely an ever-present threat. It disciplines before it attacks”.

He is saying that the main thing that motivates entrepreneurs is a fear of failure that amounts to abject terror. Keynes’ “radical uncertainty” does not only apply to the future, but also to the competition. One never knows what the competition is up to.

As Andy Grove, co-founder of Intel, understood (and every entrepreneur knows), “Only the paranoid survive.”

Have to respectfully disagree on the underlying assumptions of the article. The effort here to protect incumbent tech firms from any regulation or antitrust enforcement is amazing. The entire post is about how innovation is one of the goals that must be sought by antitrust and how competitive markets should be more innovative. Agree on that. However, when you touch on the Google subject, there is an intellectual exercise to distinguish "can be displaced" from "being displaced". You could extend this argument forever and argue that any monopolist can be potentially displaced - even though it never actually happens.