You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Okay. There is politics this week, but not how others do it. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 13,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

I build mathematical models. Yes, lots of my writing involves economics education or policy writing (both done in plain English), but most of my research, especially during grad school, involves working with models and figuring out how to use mathematics to understand a question I had. It’s a process that often puzzles most non-economists, heck, even most economists who aren’t theorists.

This week, I want to take you through my model-building process. Notice the title is “How I Build.” As you’ll see, I’m not very sophisticated. I look for the simplest possible model because that’s the one I may have a shot at doing something with. If you want advice, read Hal Varian. While not advice, I do think it is helpful to be more explicit about the ideas one has in mind. Hopefully, this convinces some people to say, “I can be explicit about what I mean and write down a model.”

Because Josh recently posted about Gary Becker’s unpublished work on indoctrination, let’s use that as a subject.

Find something interesting to you. For me, it was politics and propaganda

Okay. This didn’t start with Josh’s post. In my master’s program, I worked on political economy models and propaganda. Early in my PhD, I was interested in persuasion within politics. In my early reading of political economy, I was surprised at how little people thought about competition. When it did show up, the focus was on policy positions in elections. Median voter theorem and all that. I thought that seemed very narrow. I wrote one paper that involved narrow competition that was somewhat technical and built on popular models of the time.

Then I came across Albert Breton’s work, especially his book Competitive Governments. Breton provides a framework for understanding how competition shapes governmental behavior. He argues that governments, like firms in a market, compete to provide services to citizens. In his collection of models, this competition occurs not just through elections but through ongoing processes of policy implementation and citizen feedback. Breton emphasizes the costs governments face in securing citizen compliance with their decisions.

Political support isn’t simply given. If it were, it would be free and worthless on the margin. Instead, support is exchanged in some sense. Politicians “buy” support through various means—policies, promises, threats, and, yes, propaganda. Citizens “sell” their support, either directly through votes or indirectly through other forms of political engagement. There is a price for political support.

With this framework in mind, I set out to build the simplest possible model of the political support market. My aim wasn’t to create the most realistic model, but to write down something that could illuminate aspects of this process I hadn’t previously considered clearly. How does propaganda/advertising affect this political market? That’s what I wanted to think about. To get there, what’s the simplest model of political support? Why not treat it like a normal market? Yes, it’s very different from the market for apples. But the Hotelling model applies to political competition and gas station competition. There has to be some overlap.

Here’s the big thing that often holds people back. The point isn’t to make the most realistic model. The point is to write down a model that can say something you hadn’t thought about clearly.

Build the simplest model possible

This simplest idea came from Becker and Murphy’s work on advertising in markets: political advertising doesn’t just inform or persuade; it actually changes how costly it is for citizens to provide political support. The more you’re exposed to political messaging, the easier it might become to align yourself with a particular politician or party. It’s as if the “price” of your support has decreased.

We have two main players: politicians and citizens. Politicians want to maximize the political support they receive while minimizing their costs. Citizens, on the other hand, make choices about how much political support to provide based on their preferences and the political propaganda they’re exposed to.

Following Becker and Murphy, we model a citizen’s utility function as:

where: x = amount of political consent/support provided, y = amount of some other (numeraire) good consumed, and P = amount of propaganda/political advertising consumed.

It’s natural to assume a few things:

Providing political support is costly for citizens. In other words, support is the thing that people wouldn’t do but for some sort of return or payment.

The effect of propaganda on utility can be positive or negative. Fireworks on July 4th are propaganda. They may be cool by themselves, but they are pro-United States political propaganda.

Crucially, propaganda makes it easier to provide political support.

On the politician’s side, we have the following objective function:

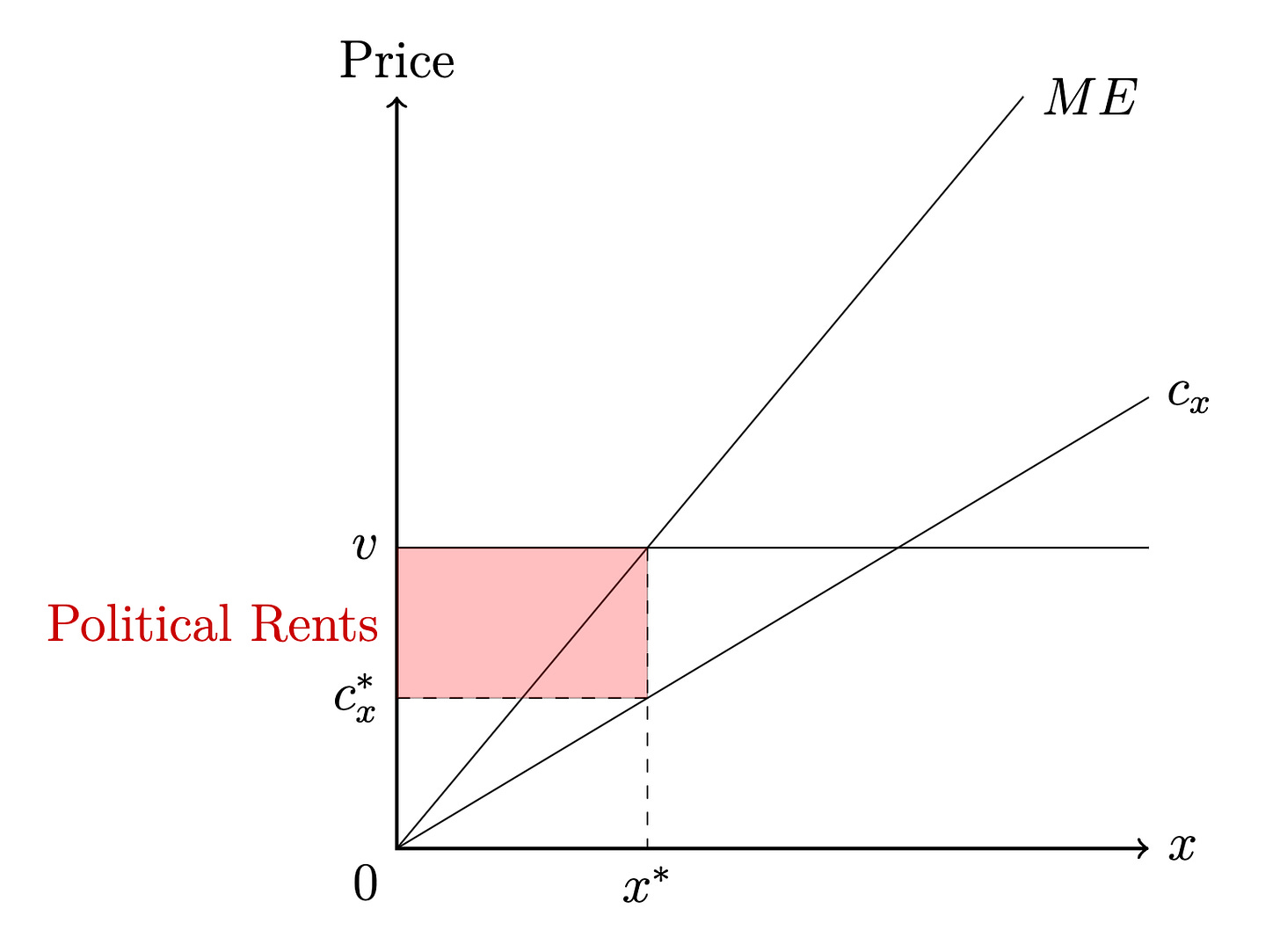

where: v = marginal value of a unit of consent (fixed), x(P) = level of consent which depends on propaganda, c_x(x,P) = marginal cost of consent which depends on the level x and the propaganda, and c_P = marginal cost of propaganda (fixed).

Of course, in simplifying this complex process into a model, I’ve sidestepped many fascinating questions. What exactly constitutes political support? Is it just votes, or does it include other forms of citizen engagement? How do politicians actually “purchase” this support? Are policies and promises equivalent to propaganda in this exchange? These are rich areas for exploration, but for the purposes of our model, we’ll need to make some simplifying assumptions.

Back to the model. If you ignore the last term and the political propaganda, this is just a buyer with some market power, often called a monopsonist. The politician earns some rents based on the value of support and how much they have to pay.

As with a normal monopsonist, when we solve this maximization problem, we get:

where ε_x is the elasticity of political support.

This equation is more interesting than it might appear at first glance. It encourages us to think about elasticities (always important) and things like the difference between average and marginal effects.

Consider what happens as ε_x changes:

If ε_x is very large (highly elastic), the term 1/ε_x approaches zero, and v ≈ c_x. This means politicians can't really underpay for support - they have to offer close to full value.

If ε_x is small (inelastic), the gap between v and c_x can be substantial. Politicians can get away with offering much less than the true value of support.

Getting back to competition, we could imagine elasticity depending on the ease in which political rivals enter or how many similar politicians already exist. Standard Cournot model stuff. More competition generates more value for the voters.

Moreover, ε_x isn’t likely to be constant. It probably varies based on the level of support already provided. This means we need to think about both average and marginal elasticities.

This framework gets us thinking about how politicians might strategically target different levels of support. They might “buy” a lot of low-level support or support from friendly voters cheaply but have to pay a premium for high-level support from core activists. None of this is some huge revelation, but the movement between the model and the world in drawing out new things you maybe didn’t (or at least I didn’t) think about.

Now, let’s look at the politician’s decision about how much to use propaganda:

This equation balances the benefits of propaganda (more support, valued at v-c_x, and cheaper support) against its direct costs spent on propaganda. The propaganda ships the marginal cost curve of support down and to the right.

Our model doesn’t just provide a static picture of political propaganda; it also gives us insights into how propaganda strategies might change under different conditions. Let’s look at some key comparative statics derived from our model:

When the gap between the value of support (v) and its cost (c_x) is larger, we’ll see more propaganda. Maybe that explains why we often see an increase in government propaganda during wars or crises when incumbent governments face less competition and have more power. The value of support increases, but the cost doesn’t rise as much, leading to more aggressive messaging. You could imagine assuming powerful dictators don’t need to do much. They’re already powerful.

When the cost of propaganda (c_P) decreases, we’ll see more of it. Again, that’s pretty obvious. But I never really thought about the cost of propaganda. It may shed light on why governments want to directly control media outlets to produce more propaganda—their cost of propaganda is effectively lower.

If propaganda becomes more effective at reducing the cost of support (larger ∂w_s/∂A), we’ll see more of it. Maybe these last two help us understand historical cases like the rise of radio in Germany. As Adena, Enikolopov, Petrova, Santarosa, and Zhuravskaya (2015) showed, radio first boosted support for the Weimar government and later for the Nazi party. The new medium made political messaging more effective, leading to its increased use.

When political competition increases, we could see less political propaganda, not more. This might seem counterintuitive at first, but think about it this way: in a highly competitive environment, citizens have more options and are less easily swayed by any single message. This makes advertising less effective and, therefore, less worthwhile for politicians. It’s like trying to shout in a crowded room—when everyone’s talking, it’s harder for any one voice to stand out.

While increased competition leads to less overall propaganda, the propaganda that does occur tends to be more effective. Why? Because when competition is fierce, only the most impactful messages are worth the investment. It’s like evolution in action—only the fittest advertisements survive. But there's an important flip side to this: when there's an abundance of propaganda, much of it turns into noise. You start ignoring the authoritarian’s picture on every street. You ignore the latest tweet.

While this model is a simplification, I hope it demonstrates the power of modeling. By distilling complex political dynamics into mathematical relationships, we gain new insights and generate testable hypotheses. This process of model-building forces us to be explicit about our assumptions and helps us uncover unexpected connections. Did we capture everything? Of course not. But honestly, I think many people will find this more useful than reading another hot take on politics.

The beauty of this approach is its flexibility. We can extend the model to incorporate forced propaganda, heterogeneous citizens, or media intermediaries. Each extension allows us to explore new dimensions of the political advertising market and generate fresh insights. That’s what model building is. Go simple to build up.

Moreover, these models provide a framework for interpreting empirical findings, like those from Enikolopov et al. (2011) who found that media competition led to 8.9% fewer votes for the Russian government. Or Besley and Prat (2006) found more media competition is more costly for the government to control. It would be nice to think more about the interplay between the different parts of the “market.”

It’s worth noting that my model, like Becker’s work on indoctrination, wasn’t published in a journal. If the goal is to publish well, I am not the person to talk to.

But that’s not the only measure of a model’s value to me. I spend a lot of time thinking about the intricacies of supply and demand, even if those are never in my publications. The process of building this model sharpened my thinking about the world, generated new insights, and opened up new questions. Whether a model ends up in a journal or not, the act of constructing it, of making our implicit assumptions explicit, invariably enhances our understanding of complex phenomena. So don’t be afraid to sketch out your ideas, to play with equations, to build your own models. You never know where they might lead you.

The power of economic modeling lies in its ability to clarify our thinking, generate testable hypotheses, and uncover unexpected connections. While no model captures every nuance of reality, even simple models can provide valuable insights into complex phenomena. So the next time you’re grappling with a challenging economic or political question, try sketching out a basic model. You might be surprised by the new perspectives and questions it reveals. After all, the goal isn’t just to answer questions but to learn how to ask new, hopefully better, ones.

That's very interesting and the mathematical model part seems great. But shouldn't you have some conception of what constitutes persuasion or political support before including it in the model? After all, if it's not something we have an independent grip on then why not just phrase the model in terms of persuasion/support expenditures. And I worry about thinking one has a grip on such notions without a specification of what sort of thing one means (may not always be the same in every use) and whether the simplifying assumptions one made are valid on that interpretation.

I mean it's really easy to think one has an idea of what it means for there to be more or less propoganda but those empirical results you mention immediately raise questions. If media competition in Russia results in more media outlets -- all of whom engage in some level of government propoganda -- does that count as more or less propoganda?

I'm a huge believer in the value of these kinds of simple models but constructing the model and deciding how to understand terms in the model in terms of the actual world aren't independent. I see perfectly good models confusing people because the way the model treats a term (eg persuasion or support) requires it be measured in some counterintuitive fashion.

For instance, our intuitive conception of political support doesn't satisfy the assumption that it's expensive -- failing to offer it during a war is often expensive. But if support is something more like coming out to vote it might satisfy that assumption but you better be aware of that difference because now support has actually decreased when something is do uncontroversial few people bother to show up to vote.

Also, I think the assumptions you made to reach conclusion 5 are somewhat unclear hence some apparent conflict with observation. Competition in markets often improve the products -- if the federal government provided the only sodas they'd likely suck -- and often a dollar spent on persuasion is more effective if the product is better (easier to make me thirsty for coke than beat juice).