I don’t care who sets the price

Economic forces matter more than appearances

There’s a folk wisdom out there that “setting the price”, meaning putting the sticker below the item or announcing what the price is for the good, means you have “control” over the price. Sellers post prices on shelves, so sellers must have power. That sort of thing.

This folk wisdom has intellectual backing. Many critics of mainstream economics argue that “administered pricing”—the fact that firms post prices rather than accepting them from some mythical Walrasian auctioneer—proves supply and demand theory fails to describe real markets. If firms are making deliberate pricing decisions, the argument goes, then prices aren’t being determined by impersonal market forces.

Both claims are wrong.

Knowing who physically announces a price tells us almost nothing about who controls that price or how the market will perform. The confusion stems from conflating two different things: setting a price and controlling a price. A firm sets a price when it announces what it will charge. A firm controls a price when it has meaningful discretion over what that price can be. These are not the same. A firm can set a price while having almost no control over it.

The folk wisdom commits a form of the animistic fallacy, something I’ve written about before. The assumption is that observed outcomes must result from someone’s intentional design. We see a firm posting a price and assume that decision “controlled” the outcome.

Basic economic theory says it cannot be true in general. Moreover, much empirical evidence, both experimental and observational, confirms the theory. “Setting” the price just isn’t that important in most cases.

Don’t mistake physical appearances for Economic Forces

As a general rule, we should not mistake physical appearances for Economic Forces. What matters for prediction is understanding the Economic Forces.

The clearest way to see this is through tax incidence, a lesson from the first month of any Econ 101 course. Suppose Congress passes a law requiring sellers to send a check to the IRS for $1 per gallon of gasoline sold. The next week, they repeal that law and instead require buyers to pay $1 per gallon directly to the IRS at the pump. Does this change who actually bears the burden of the tax?

No. The legal obligation to write the check determines nothing about the economic incidence. What matters is the elasticity of supply and demand. If demand is perfectly inelastic and supply is perfectly elastic, consumers bear the entire burden regardless of who mails the check. If the situation is reversed, sellers bear it all. The incidence divides between the two sides based on their relative responsiveness to price changes, not on the legal formality of who handles the paperwork.

As a predictive matter, the prediction is that the price should not change when Congress switches who pays it. There are subtle ways that this breaks down, but that is the starting point for thinking about any taxation.

So we should right away be wary of looking at the physical appearance and trying to figure out what it says about anything important.

Simple models that show price-setting =/= pricing power

The same logic applies to price-setting. The physical act of announcing a price, or “administering” the price, is just an administrative detail. What matters is the underlying market structure and the constraints each side faces. One could say, the Economic Forces. Okay. I will stop.

The simplest example to see the irrelevance of price-setting comes from Bertrand competition. I’ve mentioned this before, but a reminder: Two firms produce identical products. Each firm simultaneously announces a price. Consumers buy from whichever firm offers the lower price. Both firms are price-setters. Neither is a price-taker in the mechanical sense. Yet the equilibrium outcome is both firms pricing at marginal cost, earning zero profit, and the market producing the competitive quantity. If we draw supply and demand curves assuming everyone is a price-taker, the outcome is identical to Bertrand competition.

Again, setting the price and controlling the price are completely different things.

“But think about the textbook monopolist! Everyone knows monopolists set prices above marginal cost and restrict output. They post the price, so they must be “in charge” of the market.” Maybe that’s what people are thinking. But even that isn’t so simple.

Imagine that monopolist faces a perfectly flat demand curve. Every consumer is willing to pay exactly $10 for the product, not a penny more. The monopolist can set whatever price they want. They can announce $15 if it makes them feel powerful. But no one will buy. The monopolist has no actual control over the price despite being the only seller and despite physically setting that price. The competitive pressure from outside options completely eliminates any pricing power.

For those paying close attention, Bertrand and the monopolist with a flat demand curve are actually the same story.

Suppose in the two-firm case that firm B has announced a price of $10. What demand curve does firm A face? If firm A prices at $10.01, it gets zero customers—they all go to firm B. If firm A prices at $9.99, it gets all the customers. The demand curve firm A faces is perfectly flat at $10. Firm A is in the identical position as our monopolist with the flat demand curve. Both are price-setters. Neither has any pricing power.

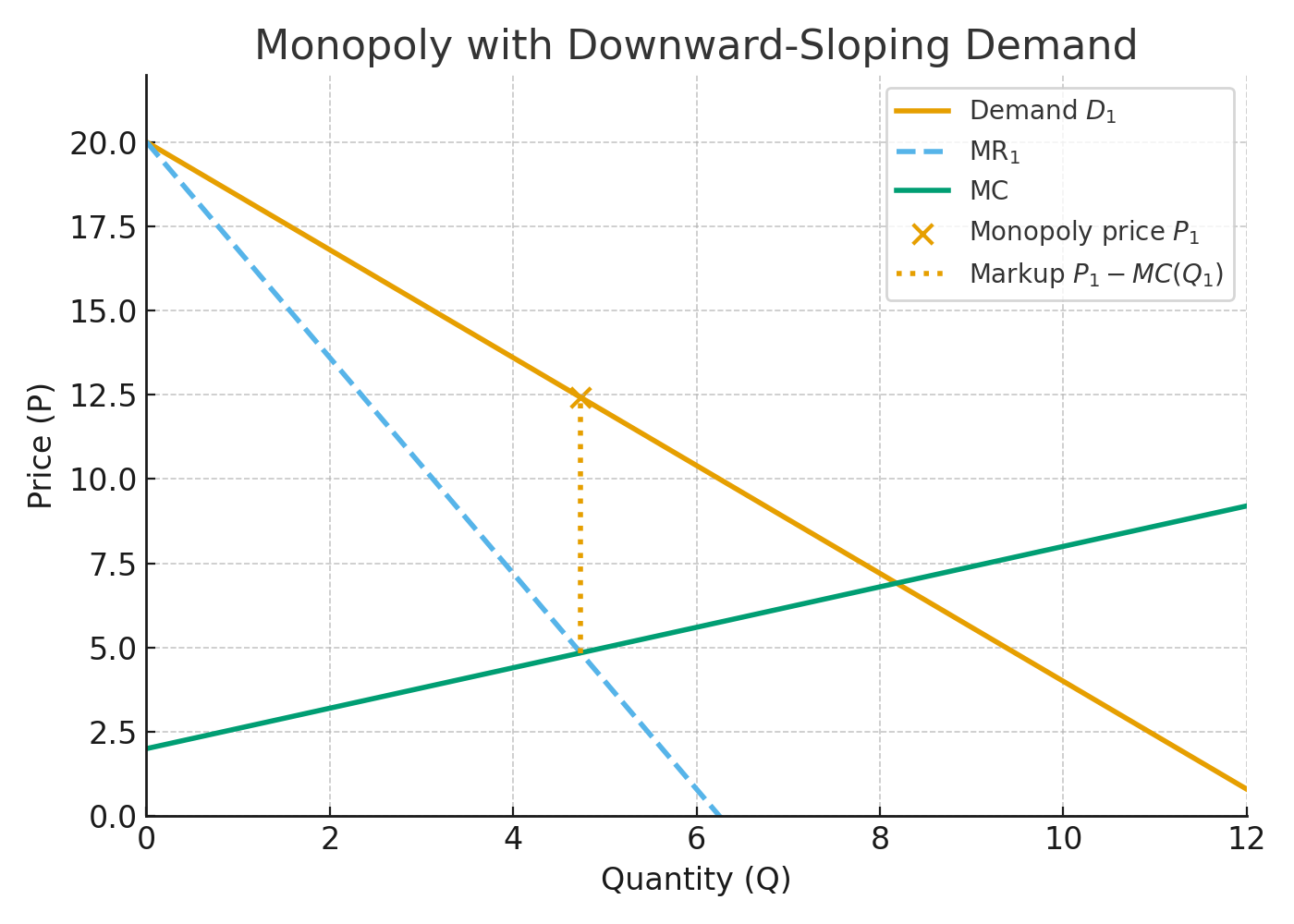

Let’s take one more variation on the monopoly model, a more standard case: a normal downward-sloping demand curve and upward-sloping marginal cost curve. Make everything linear to keep life simple. The monopolist sets the price and has some pricing power. They can raise price above marginal cost without losing all their customers.

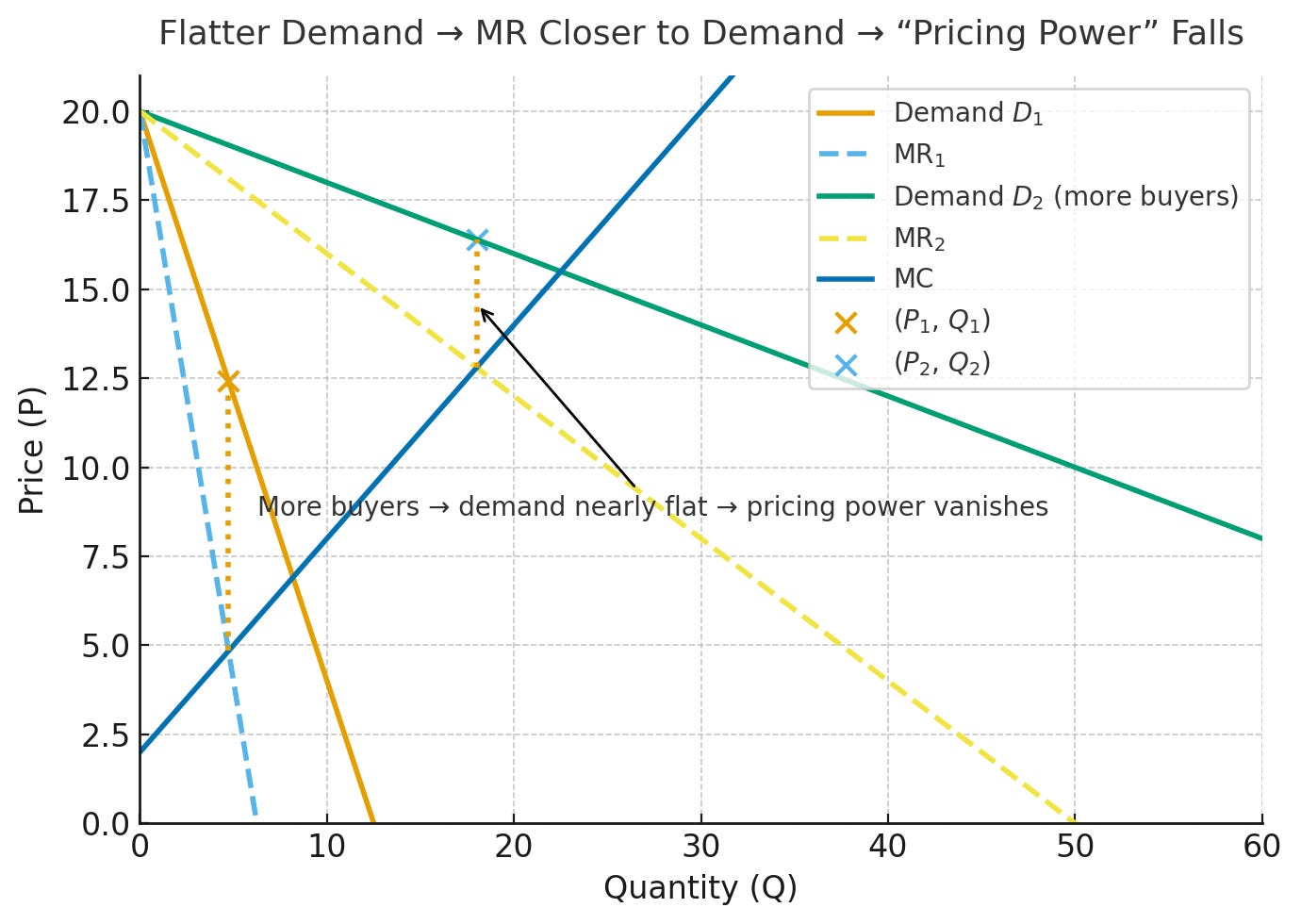

Now add more buyers to this market. What happens?

The monopolist still sets the price. That hasn’t changed. But the pricing power (in the sense of raising price above marginal cost) shrinks. More buyers makes the demand curve more elastic. The price may actually rise because demand has shifted out, but the gap between price and marginal cost narrows. The monopolist’s ability to exploit their position erodes even as the market grows. Price-setting power stayed constant. More buyers entered the market, so it may seem like the monopolist has even more power. But actually, stiffer competition between buyers means that pricing power declined. The price-setting situation stayed the same, the number of buyers increased, which the monopolist clearly likes, but pricing “power” declined in an important sense. Markups decline.

We have experiments on price-setting

Models are useful, but experimental evidence makes the point even more starkly. Let’s start with Vernon Smith’s classic work. His first experiments showed that the double auction went to the competitive outcome very quickly. Notice this already breaks the price-setting intuition. Each person can set prices, nevertheless, pricing power doesn’t exist in the competitive outcome.

“But there everyone could set prices! That’s not what we mean by administered prices.”

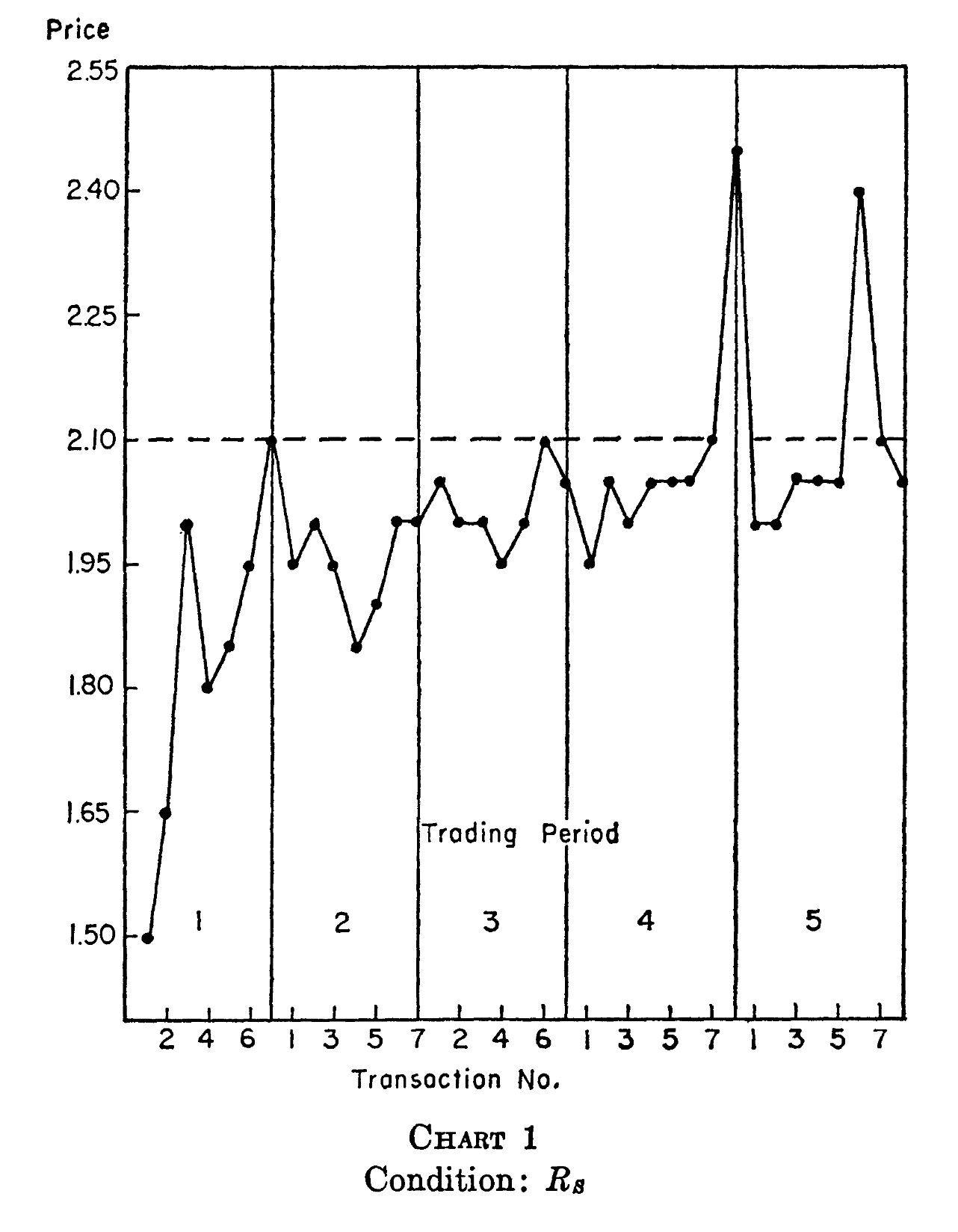

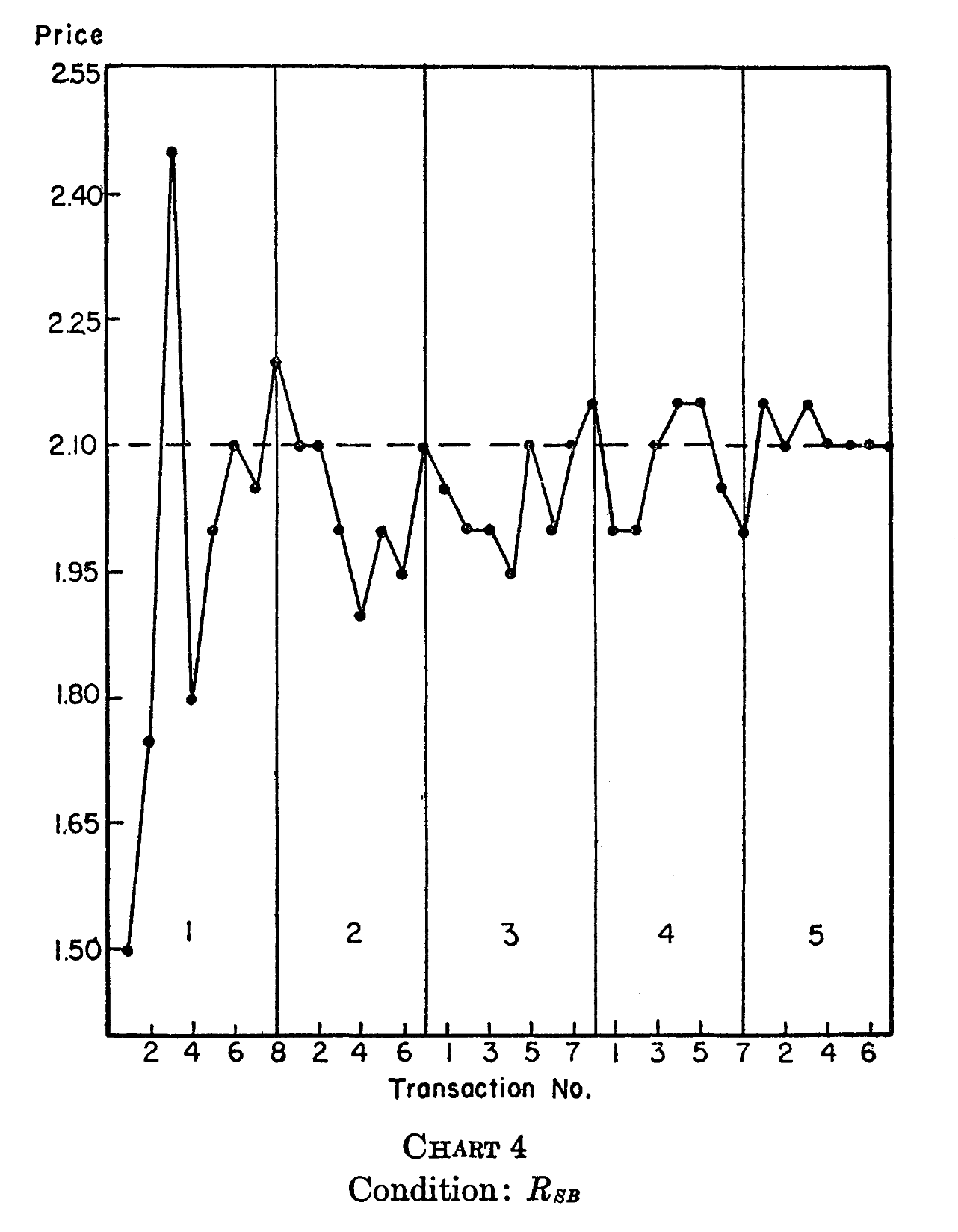

Well, Vernon Smith ran experiments that addressed this too, published in the QJE in 1964.. He compared three market organizations. In one, only buyers could make bids and sellers could only accept or reject those bids. In another, only sellers could make offers and buyers could only accept or reject. In the third, both buyers and sellers could make offers and bids in a double auction format (the original format).

The standard intuition would predict that whichever side sets prices gains an advantage. If sellers post prices, they should be able to push prices up. If buyers post bids, they should be able to push prices down. The double auction should land somewhere in between.

Smith found the opposite! When sellers were the only ones who could make offers, shown below, prices started below the competitive price of $2.10. Moreover, prices converged to a level below the competitive equilibrium. The mean price in the seller-only market was about 5% below the theoretical competitive price.

The double auction, where both sides could make offers, converged almost exactly to the competitive equilibrium. Sellers posting prices hurt them.

Smith’s explanation was that the competitive pressure falls on whichever side must reveal information first. When sellers post offers, they expose their willingness to sell. Buyers can wait and accept the best offer. This puts sellers under intense competitive pressure to undercut each other. The seller who sets the price is not “in charge.” They are at a disadvantage.

A referee reviewing Smith’s 1964 paper immediately recognized the implication. The referee noted that the findings “contradict the common assertion that administered pricing reacts to the disadvantage of the buyer.” When sellers administer prices in Smith’s experimental markets, buyers benefit. Absolutely. The basic administered pricing idea is bunk.

Pricing institutions DO matter

Does this mean the identity of the price-setter never matters? No. The market institution matters tremendously. But the relevant question is not “who sets the price” but rather things like “what information can traders observe” and “how can traders respond to prices.”

Vernon Smith, with Jon Ketcham and Arlington Williams, demonstrated this in a 1984 paper comparing posted-offer markets to double auctions. In their posted-offer institution, sellers announced prices at the start of each period. Buyers then visited sellers in random order and made purchases. Sellers could not adjust prices during the period. This is much closer to how retail markets actually work than Smith’s original 1964 design.

In some of their experimental designs, this posted-offer institution led to prices above the competitive equilibrium, as the folk wisdom suggests. The effect was particularly strong when there were only three sellers, each with different costs. In these oligopoly-like settings, the posted-offer market created opportunities for tacit coordination that did not exist in the double auction. Prices converged not to the competitive equilibrium but to something closer to a Nash equilibrium with higher prices and lower efficiency.

The point is not that pricing institutions never matter. They can matter enormously. The point is that the relevant institutional feature is not the superficial question of who physically announces the price. What matters is the competitive structure: How much information do traders have? How quickly can they respond to prices? What opportunities exist for coordination? How easily can new competitors enter?

Price setting out in the wild

I love models and experiments as much as the next guy. But what about the real world? Whatever that means. Well, since its my newsletter and I get to talk about what I want to talk about, let’s talk a bit about a paper by Chad Syverson.

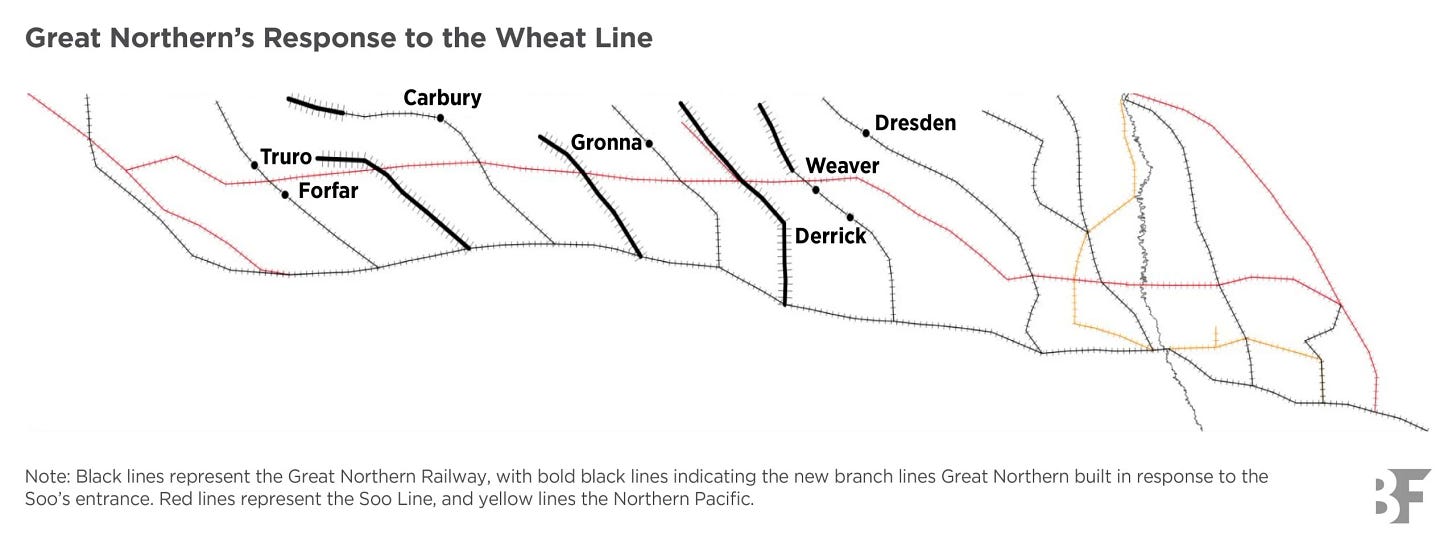

He looks at the Great Northern Railway in northern North Dakota before 1905. The railroad held a virtual monopoly over a valuable wheat-growing territory. Great Northern set rates and had real control over them. When farmers and businesspeople petitioned for new rail lines, Great Northern uniformly turned them down. Building new lines would be unprofitable given their secure position.

Then the Soo Line announced plans to build 306 miles of track through the heart of Great Northern’s territory. Nothing changed about who set prices. Both railroads posted their own prices, or tariffs. Both were “price-setters” in the mechanical sense. But everything changed about pricing power.

Great Northern responded by sprint-building 250 miles of new track across two branches, two extensions, and a purchased line. In 1905 alone, the Soo Line founded 25 new towns along its new route. Great Northern founded 26. The two railroads were competing so fiercely for territory that they overbuilt the market. Most of this branch line mileage was eventually abandoned by both companies because the competitive pressure made it unprofitable to operate.

Great Northern went from a monopolist that both set and controlled rates to a duopolist that set rates but had no control. The physical act of posting tariffs remained identical. The economic forces changed completely.

Someone might object: “Of course, a monopolist has less pricing power when a competitor enters. That’s obvious. You’re not saying anything new.” Exactly! That is the point.

Pricing power depends on competitive forces, the ease of entry, the availability of substitutes, the ability to coordinate. It has nothing to do with the trivial question of who physically announces the price. The folk wisdom gets it backward. Great Northern’s ability to post tariffs never changed. What changed was the competitive constraint on those tariffs.

The administrative mechanics tell us nothing about the economic substance. This is why the “administered pricing” point is basically always a red herring. Yes, firms post prices. Yes, managers deliberate over pricing decisions. None of that contradicts supply and demand. The Bertrand model, Vernon Smith’s experiments, and the Great Northern Railway all demonstrate the same principle: competitive forces constrain outcomes regardless of who physically announces prices.

Every firm sets its own price in the trivial sense of announcing what they will charge. What matters is whether they face competitive constraints on those prices. A coffee shop sets its price for a latte, but it has no power over that price if Starbucks is next door and customers can easily switch. Amazon posts prices on millions of products, but those prices are constrained by competition from Walmart, Target, and hundreds of other retailers selling identical goods.

The question should not be “does this firm set prices?” The answer is always yes. The question should be “what prevents this firm from profitably raising prices substantially above competitive levels?” That question forces us to examine actual competitive constraints: the availability of substitutes, the ease of entry, the cost of searching for alternatives, the ability to expand capacity, and the incentives to undercut rivals.

Not sure why anyone would care, but should the cross in the second figure corresponding to the new equilibrium be green (like demand)?

In a very narrow mechanical sense, it's the second party to agree to a transaction that sets the price. Until the sale occurs, a posted price isn't a price; it's just a dream.

It doesn't matter what the seller writes on the sticker. It isn't a transacted price unless a buyer agrees to pay it.

I've seen the phenomenon with housing prices and with ebay listings for obscure items. The active listings generally have higher prices than the completed sales. That's because the cheap ones get sold!