I read the degrowth paper, so you don't have to

Where are the prices?

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 11,500 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Wealthy economies should abandon growth of gross domestic product (GDP) as a goal, scale down destructive and unnecessary forms of production to reduce energy and material use, and focus economic activity around securing human needs and well-being.

So argues a piece by Jason Hickel, Giorgos Kallis, Tim Jackson, Daniel W. O’Neill, Juliet B. Schor, Julia K. Steinberger, Peter A. Victor & Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, published a year ago in Nature. The paper is part of a “degrowth” research program/policy agenda, which has been spearheaded by anthropologist Jason Hickel. Twitter rediscovered the piece recently, and a healthy debate (with lots of snark) ensued.

It’s a simple but bold vision. One I’m sympathetic to in principle. GDP has problems as the North Star guiding society. I personally care about more than GDP. I’m especially concerned about environmental problems in the future.

But when it comes to concrete policy, the degrowthers run into problems. This week’s newsletter will highlight some of those problems and how price theory can help us ask questions about their proposals and understanding of economics.

What is degrowth?

Proponents of “degrowth” argue that advanced economies should deemphasize pursuing endless GDP growth as an economic objective. Wealthy countries should “abandon growth of gross domestic product (GDP) as a goal, scale down destructive and unnecessary forms of production to reduce energy and material use, and focus economic activity around securing human needs and well-being.” The aim is to reduce environmental impacts while improving social outcomes.

Proponents see degrowth as possible through a “planned reduction of energy and resource use designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world.” This entails major changes like shortening working hours, guaranteeing green jobs, and realigning corporate priorities beyond shareholder profits. They argue this “can enable rapid decarbonization and stop ecological breakdown while improving social outcomes.” Specific policies include public service expansion, reduced income inequality, and eliminating economic growth’s primacy as a policy objective. The key contention is that advanced economies can and should achieve human development goals while dramatically lowering material and energy consumption. In a summary piece titled “What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification,” Hickel argues that problems today are caused by “a system predicated on perpetual expansion, disproportionately to the benefit of a small minority of rich people.”

Ignore prices at your own peril

If you’re a regular reader, your spidey sense should be going off at the degrowth discussion lacking price theory. At its essence, degrowth fails to appreciate the informational role prices play in coordinating economic activity given society's constraints.

Critically, prices provide key signals regarding social value and enable individuals to make contextual trade-offs. To use Hayek’s example, consider when the price of tin increases: “All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere.” That price conveys that tin is relatively more scarce than previously thought and relatively more socially valuable on the margin.

As always, prices reflect marginal evaluations for people in society. In contrast, Hickel et al talk about “wasteful consumption,” such as big cars and yachts. By what standard can we say something is wasteful or not? Is a big car always wasteful? What if you have a big family? Some cars are good use of resources, some bad—context dependent. It depends on the buyer’s situation but also the rest of the economies value for those inputs. Declaring certain products wholly unnecessary rejects how preferences get revealed and balanced on the margin. This embeds centralized judgements on appropriate consumption rather than learning from exchange-expressed preferences.

Markets—through prices—have a way to tell users if something is wasteful. For households, they have to spend the money and determine if the product is worth the price. For businesses, the profit and loss system helps provide the information. If a company is making a loss, that is a sign the company is turning more valuable inputs into less valuable output. You get rewarded for creating value (turning less valuable inputs into more valuable output) with profits.

The profit and loss system isn’t perfect. There are externalities which do not factor into profit or loss but create or destroy value for other people. Externalities are crucial in this discussion, because degrowth is concerned with damage to the environment, which tends to not get priced.

Even though the price system is imperfect, it still can help us address environmental issues and calculate environmental usage. Does the product use gasoline? Lumber? Does it take land? All of that will show up in prices. With externalities, prices are not perfect conveyors of value but they give SOME information. If there are two identical producers, except one tends to use more gasoline in their production, the less efficient company will make smaller profits and tend to be driven out of the market. The market will select for firms that are relatively good at using fewer resources. Prices and profit and loss do the work, if imperfectly.

Dismissing prices simply hides tradeoffs; it does not avoid them. Instead of using prices to think about costs and benefits of different goods, degrowthers have to resort to things like adding the weight of biomass and fossil fuels as a measure of waste. Do we really want to try a mechanism that rewards firms for using fewer tons of “resources” without regard to social value of those resources? The authors do not suggest that, but it’s the implicit idea if you say this is a meaningful metric of waste.

Instead, prices allow people to make tradeoffs in a coherent manner. They can decide whether the short time life of clothes is worth the monetary savings.

To be fair, current institutional contours provide no end of fodder for critique. We don’t have prices where we should. We should find more ways to price externalities when possible. Tell me what is not properly priced and let’s talk about how to price it.

Prices and markets remain deeply imperfect but radical overhaul demands properly weighing social costs against alternatives foregone. A degree of humility is warranted before scrapping growth in favor of even well-meaning visions.

Who decides what’s good and bad?

As always, the question isn’t planning or not; it is who is doing the planning. In one of my favorite books, Knowledge and Decisions, Thomas Sowell summarizes his argument by stating:

the most fundamental question is not what decision to make but who is to make it-through what processes and under what incentives and constraints, and with what feedback mechanisms to correct the decision if it proves to be wrong.

Degrowth is the opposite of this Sowellian/Hayekian perspective.

For example, a common target of degrowth advocates is the label “fast fashion” as a stand-in for unnecessary material consumption. They argue such disposable, low-cost garment production fuels waste and pollution without meaningfully improving well-being. It has intuitive appeal. Some clothes seem more “disposable” than others. I’m not too fond of more garbage, although the optimal amount is not zero. However, the term itself has no scientific or policy substance. It simply reflects a subjective aesthetic judgment. One person’s fast fashion is another person’s affordable clothing, allowing poor families to purchase more clothing than previous generations could ever imagine. For many low-income families, inexpensive clothes open access to meeting social norms or self-expression that would otherwise be unaffordable.

Does fast fashion actually require more resources? As explained above, the lower price is a sign the “cheap” clothing takes fewer resources than more expensive clothes, at least in the short term.

When degrowth proponents label fast fashion as an area for scaled-back production and consumption, they are imposing their own preferences about appropriate clothing consumption on society. Ultimately fast fashion is an arbitrary catchall for trends some academics dislike around novelty, disposability, and low costs.

Stopping fast fashion entails restricting choices for lower-income consumers according to elite taste preferences. There is no neutral economic logic defining such consumption as unnecessary. Agents reveal their preferences through exchange. Prices tell us the relative values of the people making the exchanges. A degrowth planner simply swaps their preferences via dictated production cuts and consumption constraints.

The problems with degrowth’s approach to fast fashion generalizes. Degrowth advocates can arbitrarily label some consumption unnecessary and harmful. Advertising is bad. Cars are bad. And don’t even get them started about private jets!

Notice that the degrowthers’ argument isn’t about externalities in the economic sense. They never bother to explain who is harmed by fast fashion or what we should do besides stop it. Who is harmed by advertising? Should we tax cars? Which types of cars? All cars? Gas cars?

As always, the more fundamental question is how can users discover which clothes are good and bad from this perspective? By what feedback mechanism will people figure out what fast fashion is and, therefore, what is bad? Do we have to listen to what the bureaucrats classify as fast fashion? How likely are they to update wrong ideas?

The difference in the degrowth and the economic approach matters. When economists suggest a tax on externalities, say by taxing carbon emissions, it is up to the individuals in the economy to discover how to decrease emissions.

As always, the goal isn’t to completely eliminate the thing that causes an externality but to find ways to reduce the externality and increase the overall benefits. If fast fashion is causing an externality, what is it? Garbage? Emissions?

Economists may seem to be imposing their definition of good and bad by calling things externalities, but that misunderstands the whole exercise. The point is to find out what harm to other people occurs from the perspective of those people whom they are harmed. It is a proposal to find mutually beneficial arrangements.

Absent true externalities, the degrowth agenda imposes subjective judgments about what lifestyles or production processes have social value. There is no objective economic basis for determining the “right” amount of fast fashion production. Degrowthers smuggle elite perspectives on commodification and convenience into supposedly scientific analysis. But the policy ends remain paternalistic preferences, not neutral imperatives.

Policies for degrowth

We know degrowth does not want to use prices. So what are we actually to do? The Nature piece includes the following policy suggestions:

Reduce less-necessary production.

Improve public services.

Introduce a green jobs guarantee.

Reduce working time.

Enable sustainable development.

All seem perfectly defensible. Who could be against sustainable development? However, on closer inspection, the policies are just a grab bag of goodies instead of a coherent agenda to deal with climate concerns.

For example, notice they propose a green jobs guarantee (à la MMT), not just a general subsidy of green tech. Somehow, the goal to “reduce less-necessary production” involves a call to “reduce the purchasing power of the rich.” One can only assume the rich are heavily into fast fashion.

Improved public services? Sure. But why? “Universal public services can deliver strong social outcomes without high levels of resource use.” It’s not immediately obviously governments use fewer resources. I’d at least like a caution. Because when I think government spending, I think of low levels of resources being used. (To be clear, that is sarcasm…)

You may worry about all that government spending causing inflation, so they suggest “Earmarking currency for public services reduces cost-of-living inflation.” For good measure, there is a call for a wealth tax to reduce inequality.

What does this have to do with the environment? Yeah, I’m lost too.

The Ultimate Motte-and-Bailey

The degrowth movement exhibits a classic example of the reverse motte-and-bailey fallacy. In reasoned debate, degrowth advocates start with an uncontroversial “motte” argument that societies should emphasize goals beyond GDP growth. No economist would disagree. But then they move to their ultimate “bailey” aim: imposing sweeping restrictions on economic production and consumption based on environmental and social harm claims.

When challenged on ambition or feasibility, degrowthers protect the motte position by claiming they merely argue growth shouldn’t be the paramount priority. Who could argue with that? No one thinks economic growth is the end all, certainly not in policy circles. Heck, most policy decisions are anti-economic growth. Most countries aren’t the U.S. at the forefront of economic growth. Just look at the UK, and its policy-induced, degrowth success story.

The empirical claims of degrowthers are equally evasive. The goal is not to actually reduce economic output but to reduce resource use. Which resources? How do we trade them off? Let’s put that aside. The claim is that we need to reduce GDP to reduce resource use.

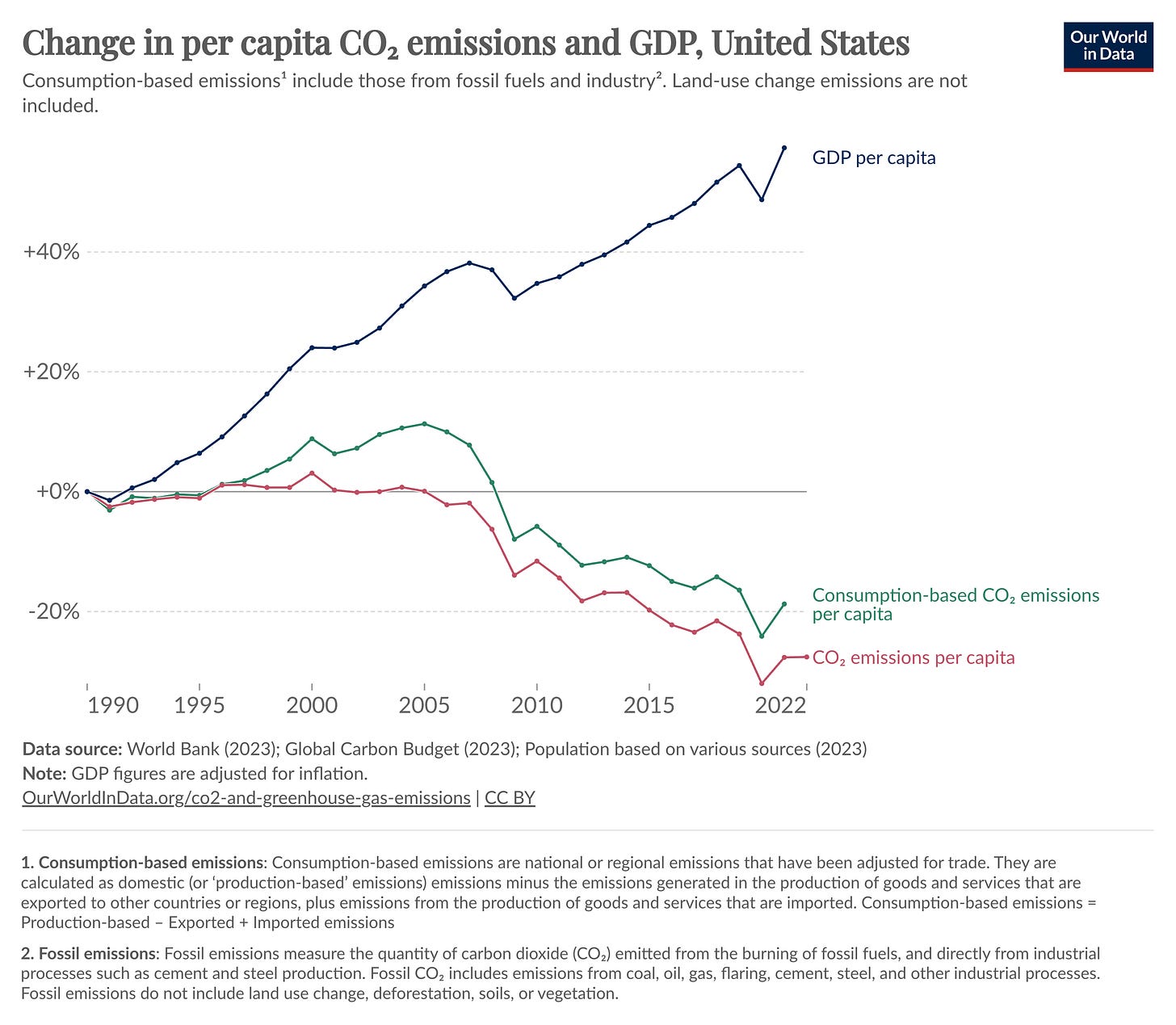

That’s not necessarily true and many examples where we see the opposite. Agriculture takes less land today while output is increasing. Countries have seen absolute falls in energy use, while GDP rise. In the US, emissions are declining while GDP is rising. This remains true even when taking into account 'offshored' emissions. For a further discussion on the empirical issues, Noah Smith has written a bunch.

How has this been possible? Policy has certainly helped. But ultimately, the US relies on prices and profit and loss to encourage innovation. Innovation means fewer resources are used. Market incentives to allow people to innovation is the only reliable way to get more output with fewer inputs. The way forward lies in harnessing prices and market incentives to balance growth and ecological needs. Externalities demand addressing via taxation or regulation. But economics teachs us that prices have to be central to the path forward.

In studying the blue economy I occasionally come across degrowth-driven groups and ideas. Like you mentioned, my spidey sense always goes off. While I am concerned about the environment and the health of our oceans, I just don’t see degrowth as a viable solution at any significant scale (or really helpful in any way).

Adding this to my lesson on economic growth. Thanks; my macro students will be glad you read the paper for them!