If Things Are So Great, Why Don't People Think So?

Many pundits say things are great. Consumer sentiment disagrees. What is going on?

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 12,500 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

In my previous post, I argued that we measure inflation wrong. That argument was based on one made by Armen Alchian and Ben Klein. They argued that a correct measure of inflation would have to include interest rates and/or asset prices. This argument, as one would expect from this newsletter, is firmly grounded in price theory. As a result, I find their theoretical argument quite convincing.

Of course, a convincing theoretical argument need not imply empirical relevance. For example, even if we cannot measure something exactly correct based on theory, that doesn’t mean that we cannot get things approximately correct. In other words, excluding interest rates and/or asset prices might be theoretically incorrect, but of no significant empirical importance.

But the reason that I brought up this argument is not just because of the solid theoretical foundation. I’m also generally curious about whether this can explain the disconnect between academic economists and the general public. When you look at surveys of inflation expectations, there seem to be a lot of people who think inflation is higher than the official measures indicate. When you read commentary from pundits who do not have an economics background or when you discuss these issues with the general public, it is not hard to find commentary about how flawed that people think the official statistics are.

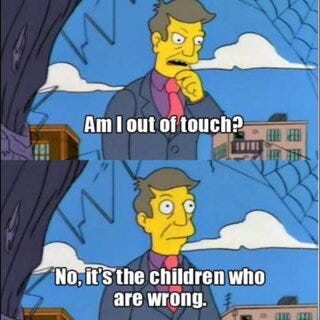

The natural inclination of experts is to conclude that non-experts are simply wrong. The non-experts don’t know as much about the topic. They don’t devote as much time to studying the issue or the data. They are extrapolating too much from personal experience and anecdotes. Perhaps the experts are correct on these points. However, I’m less inclined to default to that position. This is especially true when it is not just “vibes,” but actual data that suggest a disconnect between what people are experiencing and what the official statistics say.

We are currently in a period where this is happening. Some mainstream news publications and some academic economists are publicly proclaiming that the economy is doing great. However, the general public seems to disagree. But rather than dig into why the general public disagrees, these pundits and economists seem content to conclude that the public is wrong or just needs to receive better messaging.

My own view is that when things are great, you don’t really have to tell people that they are great. Thus, we might want to try to figure out what is going on here.

Put differently, here is the critical puzzle in the data that calls out for resolution. The inflation rate has fallen pretty dramatically from its peak. The unemployment rate is low. And yet consumer sentiment remains low. The puzzle here is that there is generally a pretty tight co-movement between measures of consumer sentiment, the inflation rate, and the unemployment rate. If inflation has fallen, why hasn’t consumer sentiment risen?

One possible reason is that Alchian and Klein are correct. Perhaps a correct measure of inflation would be higher than the official statistics and this can explain why consumer sentiment is down.

In fact, this is the point made in a new paper by Marijn Bolhuis, Judd Cramer, Karl Schulz, and Larry Summers. Although they arrive at their insight independently of Alchian and Klein, they effectively make a similar argument: measures of the price level should include the “cost of money.” To examine whether this matters, they construct an alternative measure of the consumer price index (CPI). They replace owners’ equivalent rent as a measure of the cost of housing with the measure that was used in the calculation of CPI prior to 1983: homeownership costs that captured changes in housing prices, interest payments, property taxes, insurance, and maintenance costs. They also replace the retail price of cars with the average lease payment on a car and they add personal interest payments as an additional item in the index. Below is Figure 10 from their paper, which plots a comparison of their estimate of inflation using their alternative measure of CPI (using housing costs and personal interest payments) along with inflation as measured by the official CPI.

As is evident from the figure, their alternative measure suggests that the inflation rate was much higher than the official CPI measurement would suggest. Rather than peaking at around 9%, their alternative measure suggests that inflation actually peaked around 18%. And rather than falling to 3% by the end of 2023, their estimate suggests that inflation was around 9%.

A skeptic might critique the paper by saying “sure, you have this alternative measure. So what? Why should one prefer this alternative measure to the official measure?” To this, there are two responses. First, although this paper motivates the inclusion of interest payments through intuition about the price level and the cost of living, Alchian and Klein have made the necessary theoretical argument to prefer a price index that includes interest rates. Second, the authors use their alternative measure of inflation to see if it can explain why consumer sentiment is low. They show that replacing the official inflation rate with their inflation rate can explain 70 percent of the gap between predicted consumer sentiment and actual consumer sentiment. This suggests that their measure is picking up on what consumers care about. Taken together, these two points provide evidence for why we should take their measure of inflation seriously.

They then show that this characteristic is not unique to the United States. They show that movements in interest rates are capable of explaining gaps between predicted consumer sentiment and actual consumer sentiment in 10 developed countries.

Thus, despite any specific qualms one might have about their paper itself, it does seem to do a good job of explaining why consumer sentiment is low even though all of the experts are saying that things are great. This shouldn’t be surprising. When things are great, you generally don’t have to go out of your way to tell people. But another major lesson of the paper is that it gives some credence to Alchian and Klein’s claim that we measure inflation incorrectly.