Instacart's price discrimination isn't price discrimination

On the meaning of price discrimination

This week’s newsletter originally appeared on Truth on the Market, a website full of scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more. Since it’s about a favorite topic of Economic Forces, I thought it would be of interest to readers.

On a Thursday in early September, more than 40 strangers logged into Instacart to buy eggs and test a hypothesis. They all selected the same store, the same brand, and the same pickup option. The only difference was the price they were offered: $3.99 for some, $4.79 for others.

We are, of course, supposed to not only be shocked by this, but also outraged. The Groundwork Collaborative, which organized the study, warned that companies like Instacart are jeopardizing trust in markets.

The New York Times ran it as the hook for a larger piece on algorithmic pricing: “the notion of a single price, offered to all customers for a predictable period, is breaking down.” The Times piece ends with Groundwork Executive Director Lindsay Owens saying: “This isn’t about managing scarcity or efficient markets… [It’s about] pushing to figure out the maximum amount you are willing to pay and squeeze it out of you.”

Both pieces blur together several distinct ideas: that prices vary, that prices are set by algorithms, that algorithms use your personal data, and that all of this harms consumers. But these are not the same thing.

Importantly, the study actually found no evidence that Instacart based prices on individual characteristics. As the Times piece correctly notes: “The Groundwork study found no evidence that Instacart was basing different prices on customers’ individual characteristics like income, ZIP code or shopping history.” Yet Groundwork uses the findings to call for Federal Trade Commission (FTC) action against “price discrimination not justified by differences in cost or distribution.” The Times frames the study as evidence of a trend toward algorithmic price discrimination.

To see why this leap fails, consider that there are at least four distinct reasons you might see different prices for the same product.

Four Reasons You Might See Different Prices

Randomized pricing experiments (A/B testing)

Some shoppers randomly see $3.99 for eggs; others see $4.79. The purpose is to learn how price-sensitive the market is across different product categories. This is standard A/B testing, the same methodology that virtually every online company uses to improve its products.

Netflix tests different thumbnail images. Retailers test prices. Random YouTubers, even tiny ones, test thumbnail placements. Over on Substack, I can A/B test article titles.

In the case of pricing, the randomization means the prices are not based on any individual characteristics. You get $4.79 for eggs because a random number generator assigned you to that treatment group, not because an algorithm profiled you.

Why would a company do this? When I teach my students about monopoly pricing, I draw the demand curve and assume the monopolist knows that curve and picks the optimal price. But real companies don’t see the demand curve. They want to learn how quantity demanded changes with price. Randomized experiments are how you learn.

Strategic randomization

Even without learning motives, firms might randomize prices as a competitive strategy. The intuition: if you always charge $5, your competitor charges $4.99 and steals your customers. If you always charge $4.99, they charge $4.98. In the jargon of game theory, no pure strategy equilibrium survives.

Instead, sellers randomize. Each seller picks one probability distribution over prices—not tailored to individuals, just one strategy for the whole market. Different customers end up paying different prices, but not because anyone profiled them. They just happened to show up when the price was high or low.

In practice, it can be hard to tell strategic randomization from price discrimination. A “sale” could be a random price variation, or it could be targeting price-sensitive shoppers who wait for discounts.

Dynamic pricing

Prices adjust over time in response to supply and demand. Uber’s surge pricing is the standard example: when demand spikes after a concert, prices rise to attract more drivers. Airlines do this. Hotels do this. The prices adjust based on observed market conditions, not based on individual profiles.

It’s not always easy to tell what is true dynamic pricing. Is an early-bird discount reflecting lower costs, lower demand for food services, or a strategic targeting of older people or people who are more flexible in terms of time? In practice, it can be both, but we can conceptually separate the ideas.

Price discrimination

Actual price discrimination is charging different prices for goods that are identical from the seller’s perspective, based on consumers’ willingness to pay. Senior discounts, student pricing, and coupons are all forms of price discrimination. The fear driving the Instacart coverage is that algorithms will profile you and charge you the maximum you’ll pay, which is an extreme version of price discrimination. This is the one that everyone seems worried about (I’ll say more on that later).

Again, it may not always be possible to tell these apart in practice. But we should be clear that these four phenomena have different causes, different welfare implications, and require different policy responses, if any.

The Narrative vs The Evidence

This brings us back to Instacart. The company says its pricing tests are “short term, randomized,” “never based on personal or behavioral characteristics,” and “never change in real time, including in response to supply and demand.” That’s a description of A/B testing. I’m not saying we should necessarily believe what they say, but the Groundwork study—despite its framing—found no evidence to the contrary.

The evidence, which is always subject to revision, points to category one. The narrative assumes category four. After reporting that the study found no evidence of personalized pricing, the article pivots: “But there is little doubt that Instacart and other online sellers have the ability to do so.” A volunteer speculates: “If they know how you shop, even on other items, they can use all that information to say, ‘We’re going to tailor the price to you… We’re going to get the maximum amount of money out of you that you’re prepared to pay and drain your pocketbook.’”

The article then notes that “Companies including Delta Air Lines, Amazon and Home Depot have been accused of experimenting with such personalized pricing, only to retreat after consumer backlash.” And it cautions that frequent price changes “could make it easier for companies to adopt personalized pricing strategies in the future.”

This is a story about something that might happen, not something that did happen. The study found randomized A/B testing. The narrative is about algorithmic profiling.

Would Banning Price Experiments Help Consumers?

Grant for a moment that A/B testing itself could be a concern. The implicit assumption in the discourse is that banning price experiments would help consumers. Stop the randomization, get stable prices, and consumers win.

But which stable price would Instacart use?

Let me pose a question that I posed on Twitter. For what classes of downward-sloping demand curves would consumers prefer the stable price to randomized prices around the same average?

The answer: none.

The intuition is that when prices are high, you buy less and limit your losses. When prices are low, you buy more and capture gains. The gains from low-price periods outweigh the losses from high-price periods.

The intuition that price stability being good helps consumers implicitly sneaks in an assumption about risk aversion that isn’t part of standard consumer-surplus analysis. Maybe you want to make that argument. Fine. But you should be aware that you’re making an argument that contradicts basic consumer theory.

Why Price Discrimination Isn’t Always Bad

So, the Instacart study found A/B testing, and I gave a simple (silly) counterexample where banning A/B testing wouldn’t help consumers anyway. That’s not the only thing at play, but we can’t just assume our intuition about constant pricing will ultimately help consumers.

Here’s what I find strange about the whole episode: we know companies engage in price discrimination. Senior discounts, student pricing, coupons, and loyalty programs are all price discrimination, out in the open, every day.

Spotify charges students $5.99 and everyone else $11.99 for the same service. Amazon Prime costs $6.99 per month if you’re on Medicaid, $14.99 if you’re not. Airlines have turned price discrimination into an art form. If Groundwork wanted to document price discrimination, they could walk into any grocery store and photograph the signs, or just open any app on their phone.

And even if they had found true personalized pricing (which they did not), the framing would still be overblown. Price discrimination sounds bad. The word “discrimination” does a lot of work there. It’s almost as scary as “algorithm.” Alexander MacKay of the University of Virginia, quoted in the Times, made this point: “Many pricing strategies resulted in higher costs for less price-sensitive, and therefore potentially higher-income, consumers, while lower-income consumers paid less.” Sure, that’s discrimination, but is it bad for consumers?

Remember the basics of monopoly theory. A monopolist charging a single price faces a tradeoff: lower the price to sell more units, or keep the price high and sell fewer. The monopolist leaves some transactions on the table; consumers who would pay more than the cost of production but less than the monopolist’s chosen price. This generates the standard deadweight loss from monopoly, and it’s why antitrust cares about market power in the first place.

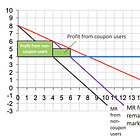

The ability to use price discrimination changes the calculus. If the monopolist can charge different prices to different consumers, it can sell to those marginal buyers without lowering the price for everyone else. Output expands. The transactions that were left on the table now happen. In the extreme case of perfect price discrimination (charging everyone exactly their willingness to pay), the monopolist produces the efficient quantity.

People may worry that consumers don’t get the benefits of that output expansion. But that’s just the textbook case with a single seller. With competition, the results can be even better for consumers. In my theoretical research, I’ve found that price discrimination with competing firms can maximize consumer surplus. Competition forces firms to fight over price-sensitive consumers, while still serving the broader market.

Whether price discrimination helps or hurts consumers is an empirical question with a long literature. The answer varies by context. The empirical work is mixed but hardly supports blanket opposition. What you don’t find is evidence that price discrimination is systematically bad for consumers.

The Real Question

There are legitimate questions about algorithmic pricing that are only going to become more important. How do algorithms affect competitive dynamics? When does price variation reflect learning versus extraction? How much transparency should consumers have about how prices are set?

But the Instacart study doesn’t begin to touch these questions. It found that a company runs A/B tests on prices, something that’s been standard practice in retail for decades, just done now with digital tools. The innovation is speed and scale, not the basic practice.

Economics is not just an intuition pump. When someone says “this feels unfair,” we need to ask: compared to what? Compared to everyone paying the lowest price? That’s not happening. That’s not a plausible counterfactual. Compared to everyone paying the same price? Consumer-surplus theory says randomization around the same average price actually benefits consumers.

Price theory exists to cut through exactly this kind of confusion. Let’s use the tools we have.

For more on price discrimination, check out the following newsletters.

I sometimes think I am the last of the hardcore anarchists or ... something. My first reaction was, "So what? It's their store, their prices, their goods. Buy or don't buy." My second reaction was, if it's gaming you, game it right back. Find out what it uses to discriminate, and use that to get lower prices.

Government is not the solution. Anyone who thinks it is, is afraid to shoulder any personal responsibility for making their life better.

This brings back fond memories of my childhood. My family moved, in 1957, from one neighborhood to another, and I acquired a new set of friends. One day after playing baseball we all went into the Mom 'n Pop grocery store for candy and soda pop, when they all pulled out coupons for a variety of products that were not for candy and soda pop. The owner readily accepted them. No hesitation whatsoever.

My first lesson in price discrimination.