Prices are signals (and politicians keep shooting the messenger)

Economic policy insight #1: A price is a signal wrapped in an incentive.

In November, I outlined eight economic insights that matter for policy. I promised to explain them one by one. It’s taken me months to get to this newsletter—not because I forgot, but because this concept is a central part of the book I’m working on. I wanted to make sure I had all the parts lined up, all 5,000 words of them.

This is the most central insight from economics, and every other one depends on understanding it:

A price is a signal wrapped in an incentive. Prices aren’t just good or bad numbers—they tell us what’s scarce while creating pressure for change.

When most people see a high price, they see a problem. (Unless the “price” is their wage, then everyone is happy with a high price.) Politicians get elected by promising to “do something” about high prices. But economists see prices as something different: a piece of information that’s telling us something important about the world, paired with a built-in mechanism to address the underlying issue.

Prices are the nervous system of the economy—they transmit vital information throughout the entire economic body without any central coordination. Every day, billions of economic actors make decisions based on prices. Should I buy this house? Should we manufacture more refrigerators? Should I become a software engineer? Prices guide these countless choices, while providing the decentralized coordination that makes complex modern economies possible.

What makes this system remarkable is that it requires no mastermind, no central planner calculating how many toothbrushes to produce or avocados to ship. Instead, prices emerge naturally from the interactions of buyers and sellers, each pursuing their own interests yet collectively generating an intricate web of information and response that no single mind could conceive.

The Wonders that Prices Generate

Consider the seemingly mundane reality of supermarket shelves stocked with diverse products—fresh bananas from Ecuador, wine from France, and cheese from Wisconsin—all coordinated seamlessly without a global food czar. One of the core insights of economics is decentralized coordination can actually work, despite no single person or agency guiding the process.

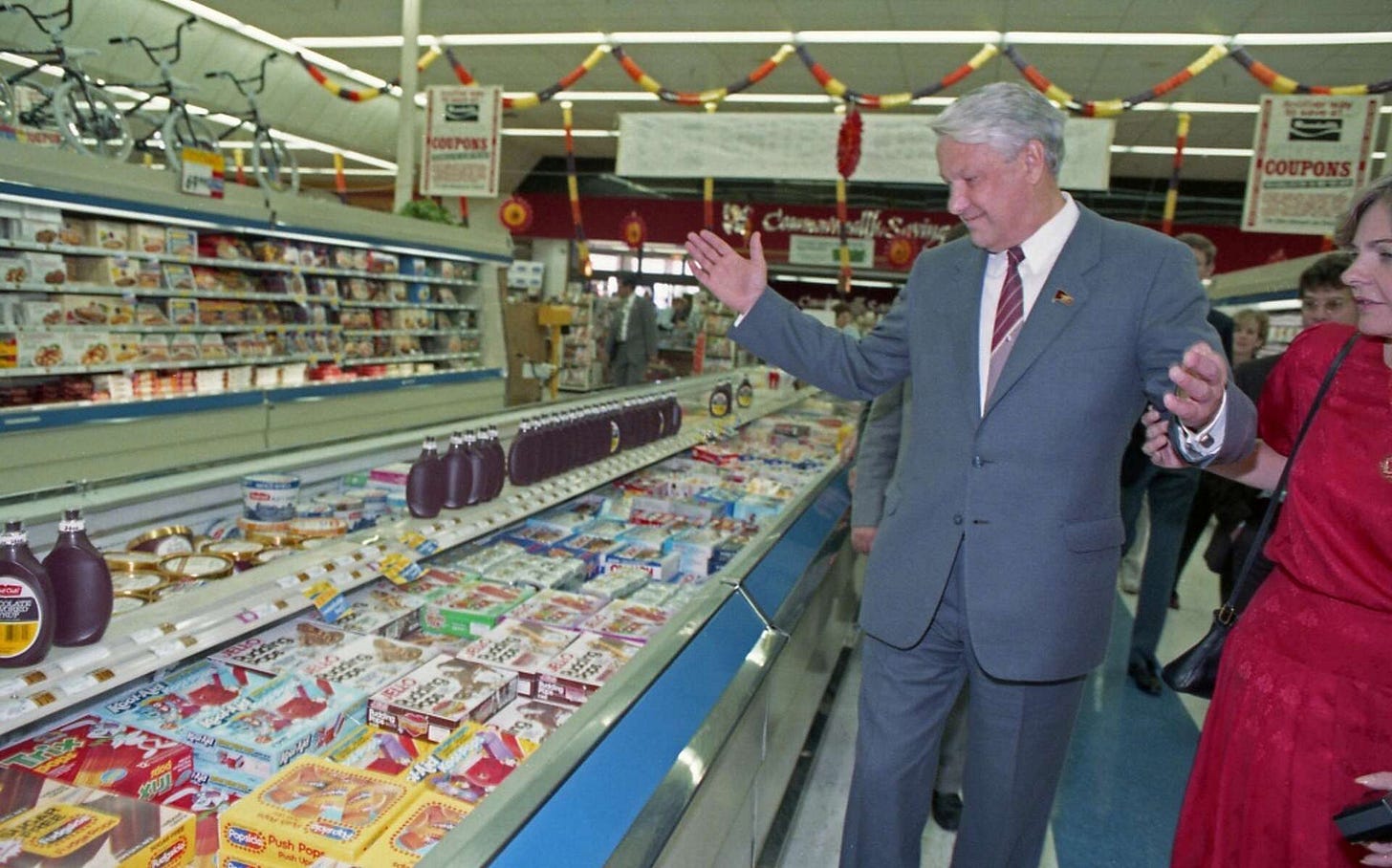

This phenomenon famously astonished Boris Yeltsin during an unplanned visit to a Houston-area Randall’s supermarket in 1989. The future Russian president was visiting NASA when he insisted on making an impromptu stop at a typical American grocery store. According to witnesses, Yeltsin was stunned by the abundance and variety of goods available to ordinary Americans. He wandered the aisles in disbelief, asking whether this was a special store set up for dignitaries or truly available to everyone.

“Even the Politburo doesn’t have this choice. Not even Mr. Gorbachev,” he reportedly said.

Later, Yeltsin would reflect that the experience shattered his faith in the communist system. “When I saw those shelves crammed with hundreds, thousands of cans, cartons and goods of every possible sort...I felt quite frankly sick with despair for the Soviet people,” he wrote. “That such a potentially super-rich country as ours has been brought to a state of such poverty! It is terrible to think of it.”

What stunned Yeltsin—and what we take for granted—is the miracle of price-driven coordination. This communication happens without anyone coordinating it. No central planner needed to announce a lumber shortage—the price did it automatically. This is what Friedrich Hayek called the “marvel” of the price system. It collects and distills vast amounts of dispersed knowledge that no single person or agency could ever gather. And markets are uniquely efficient in their information requirements. When the price of a good increases, consumers don’t need to know why it increased—whether from supply chain issues, increased demand, or resource scarcity. All they need to know is that the price went up, which automatically communicates that the resource has become more valuable elsewhere.

The miracle here lies in the simplicity and power of price-driven coordination. Prices rapidly adjust to reflect real-time shifts in demand, resource availability, and innovation, allowing people around the world to respond swiftly, efficiently, and rationally. Nobody needs to know the intricate details of why bananas are abundant or wine prices are rising; prices distill and communicate this vast amount of knowledge. As an empirical matter, the decentralization inherent in the price system outperforms even the most sophisticated attempts at central planning precisely because it harnesses dispersed, localized knowledge and incentives.

The key idea is that prices aren’t just arbitrary numbers—they’re packed with information. When lumber prices tripled during the pandemic, that spike wasn’t just a pain point for homebuilders. It was conveying crucial information: “We don’t have enough wood right now.”

But prices do more than just inform—they motivate action. A signal wrapped in an incentive, to use Alex Tabarrok’s phrase. That same high lumber price that signaled scarcity also created powerful incentives to fix the problem:

For consumers: “Maybe hold off on that deck renovation or find alternative materials.”

For producers: “Ramp up production—there’s money to be made.”

For entrepreneurs: “Develop wood alternatives or more efficient harvesting methods.”

This dual nature—information paired with motivation—makes prices uniquely powerful for coordinating economic activity.

Prices are also subtle things. That’s one of their strengths. They enable incremental, fine-tuned adjustments rather than drastic all-or-nothing decisions. Consider milk allocation: dairies don’t make binary choices about sending all milk to cheese or all to ice cream production. Instead, they constantly adjust the margin—perhaps diverting just 2% more milk to yogurt when its price rises slightly. Each gallon of milk flows to its highest-valued use, with producers using only the amount that justifies its value in alternative applications. This constant calibration happens millions of times daily across the economy, preventing both wasteful excess and painful shortages.

Profit-Seeking Entrepreneurs: Making Price Signals Count

A critical piece of the story above is the incentive embedded in a high price. A high price is basically an invitation for problem-solvers to profit. If gas is $5 a gallon, any entrepreneur who can drill oil, refine fuel, or transport gasoline has a strong motivation to do so quickly. If rents are sky-high, developers stand to make money by adding rental units – if they’re allowed to build. The profit motive is what translates the price signal into real-world action.

Consider what happened during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: When hand sanitizer vanished from store shelves and online prices soared to $50 or more per bottle, an extraordinary entrepreneurial response unfolded. Within days, distilleries across America—from industry giants like Anheuser-Busch to small craft operations like Old Fourth Distillery in Atlanta—pivoted from producing spirits to manufacturing hand sanitizer.

These businesses weren’t acting from pure altruism (though many did donate products to first responders). They were responding to price signals indicating extreme scarcity but from their perspective they are responding to the sweet allure of profit. Almost overnight, distilleries reconfigured production lines, navigated unfamiliar FDA regulations, sourced new ingredients, and created distribution networks for an entirely different product. In Portland, Oregon, Shine Distillery rapidly went from concept to production after founder Jon Poteet realized their waste alcohol could be repurposed. No government agency ordered this remarkable shift—it emerged organically as entrepreneurs spotted both a pressing need and a profit opportunity. The high prices that initially alarmed consumers were precisely what mobilized this rapid, creative response.

This widespread entrepreneurial response only happens because the potential reward is there – the high price covers the extra costs and risks of jumping in to help. Without profit, a price signal is like an alarm with no firefighters; it rings, but nobody comes. We will see examples where we see the opposite of a rapid solution because prices aren't allowed to signal scarcity.

This focus on profit makes sense, but it’s only half the story. People talk about markets as a “profit system” but losses are equally crucial—though far less appreciated. In a functioning economy, losses serve as signals every bit as important as profits. They indicate where resources are being misused or wasted, compelling producers to stop activities that consumers no longer value enough to pay for.

Consider automakers stuck with unsold cars. Those vehicles represent not just lost revenue, but lost opportunities—valuable resources that could have been better used elsewhere. The pain of losses forces companies to rethink, adapt, and redirect resources to more valuable uses. Without losses, producers might continue wasting scarce resources on unwanted products. Just as profits motivate producers to ramp up supply, losses compel them to cut back, ensuring resources are freed up for better uses elsewhere in the economy.

This feedback loop of profit and loss is what allows decentralized markets to continuously adjust, learning from countless small errors rather than compounding them, as often happens in centrally planned economies or in markets distorted by heavy-handed interventions.

Why Understanding Prices Especially Matters Now

Understanding prices as both signals and incentives is extraordinarily relevant to many of our most pressing policy challenges today. From housing affordability to climate change, getting prices right could be the difference between effective solutions and costly failures. When California electricity prices spike during peak hours, that’s telling us something important about capacity constraints and creating incentives for conservation.

Yet despite their importance, today’s political climate increasingly rejects the wisdom of price signals. As Ryan Bourne puts it, there’s a “War on Prices” happening across the political spectrum. Both parties routinely propose price caps, controls, and subsidies that mask underlying market realities. We see politicians promising to “end price gouging” on everything from housing to groceries to pharmaceuticals—as if prices were arbitrary numbers set by corporate villains rather than reflections of genuine scarcity.

Consider the ongoing egg price controversy. When avian flu wiped out millions of chickens and egg prices doubled, politicians and regulators immediately jumped to conclusions about “price gouging” and market manipulation, ignoring the fundamental elasticity principles that predict exactly such price spikes when supply drops in markets with inelastic demand. This misdiagnosis threatens to produce harmful policies—if you believe high prices stem from corporate manipulation rather than genuine scarcity, you’re likely to implement price controls rather than policies that would encourage increased production.

This call for price controls is becoming a new norm, especially since inflation rose during the pandemic. Kamala Harris’s campaign proposal last summer to ban “price gouging” on groceries exemplifies this disregard for price signals. By framing price increases as unfair rather than informative, such policies ignore that inflation fundamentally results from too much purchasing power chasing too few goods. Prices rise because demand exceeds supply—not because of corporate plots.

When prices can’t rise to reflect genuine scarcity, we lose both components of the price mechanism: the signal and the incentive. Consumers have no reason to moderate their consumption of increasingly scarce goods, while producers lack motivation to increase supply. Instead of addressing root causes—supply constraints or increased demand—price controls merely mask these problems while making them worse.

People will mock the idea that supply responds in a crisis. “Oh, are people going to magically make more generators?” But that’s thinking too narrowly about the here and now. Firms are also deciding whether they want to be ready to respond. As Jason Furman noted, “If prices do not rise in response to strong demand, new companies may not have as much inclination to jump into the market to ramp up supply.” The most promising path to sustainably lower prices is expanded production capacity, but this requires the profit incentive that price controls eliminate.

Consider recent energy transition policies. Rather than leveraging carbon prices to incentivize lower emissions while allowing markets to find efficient solutions, many policymakers prefer command-and-control regulations that mandate specific technologies or production methods. This approach sacrifices the discovery process that market prices enable, often at enormous cost.

Housing policy suffers similarly. Instead of recognizing that high urban rents signal the need for more construction and reformed zoning, politicians push rent control and subsidies that address symptoms while allowing the underlying shortage to worsen.

The alternative—pretending we can simply dictate prices without consequences—has failed repeatedly throughout history, from Nixon’s price controls to Venezuela’s price-capped supermarkets with empty shelves to the Soviet Union’s perpetual shortages of basic consumer goods.

To combat this, we need price theory—not the overly mathematical models that dominate academic journals, but the core insight about how decentralized decision-making coordinates activity better than any central planner ever could. It’s the economic equivalent of the invisible hand, except that prices give us a visible mechanism for how it all works (if we are looking and have the tools of price theory).

Price Controls, or When We Ignore Price Signals

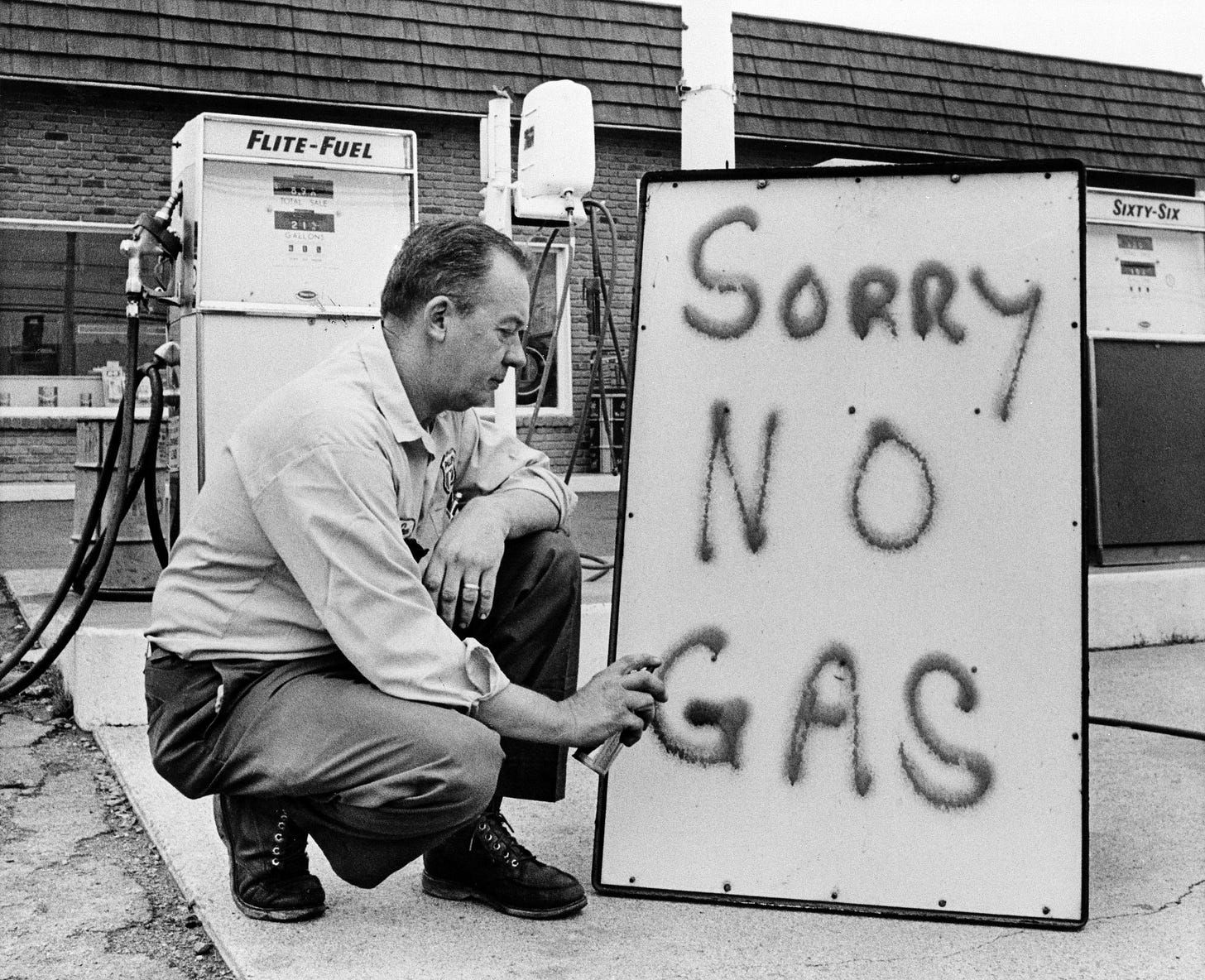

Policies that suppress price signals often backfire spectacularly. Take price controls during emergencies. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of this principle comes from America’s gasoline crisis of the 1970s. When the Nixon administration imposed price controls in response to the OPEC oil embargo, the result wasn’t affordable gas—it was no gas at all. Drivers across the country endured infamous lines that stretched for blocks, sometimes waiting hours just to fill their tanks. Gas stations hung “SORRY, NO GAS TODAY” signs, while others limited purchases to odd or even license plate numbers on alternating days.

The human and economic costs were staggering. Mothers ran out of gas while taking children to school, workers were unable to commute, and even violence erupted at filling stations. One man was arrested for pulling a gun on a gas station attendant who refused to fill his car because it was the wrong day for his license plate number. Meanwhile, a thriving black market emerged where people paid far more than what would have been the market price without controls. Some drivers ventured out before sunrise to fill up.

When controls were finally lifted, prices initially jumped but then fell as increased production and conservation measures took effect. The lines disappeared overnight—not because gas suddenly became abundant, but because the price system could once again efficiently allocate the scarce fuel and incentivize increased supply.

Housing

The same principle applies across countless markets. Consider housing and rent control policies. When cities impose rent control, they’re essentially shooting the messenger that’s telling them, “We need more housing.” The price cap might help current tenants temporarily, but it discourages new construction and maintenance of existing units. Socialist economist Assar Lindbeck asserted, “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.”

More recently, landmark study by Diamond, McQuade, and Qian on San Francisco’s rent control expansion found that while the policy achieved its short-term goal of helping incumbent renters stay in place, it had dramatic unintended consequences. Landlords responded by converting rental units to condos or redeveloping buildings to exempt them from rent control. This reduced the rental housing supply by 15 percent and actually drove up citywide rents in the long run.

Specifically, they found:

Rent-controlled buildings were 8 percentage points more likely to convert to condos

Rent control led to a 15 percentage point decline in the number of renters in treated buildings

The lost rental housing was replaced by properties catering to higher-income residents

This ultimately contributed to gentrification—the exact opposite of what the policy intended

This mirrors findings from other cities. Studies from across the country show that rent control typically shrinks the housing supply and actually increases rents in the long run by turning off the signal and incentive for more construction.

The contrast between historical and modern responses to housing crises demonstrates this principle vividly. When the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed over half of San Francisco’s housing stock—an estimated 28,000 buildings housing 250,000 people—the city faced a catastrophic housing emergency. Yet remarkably, San Francisco avoided prolonged homelessness or housing shortages despite this devastating loss.

Why? With no rent control or price caps, housing prices rose immediately, creating powerful incentives for rapid adaptations. Homeowners converted garages and added rooms to rent. Nearby communities quickly built new housing. Entrepreneurs established tent cities that transitioned to wooden structures within weeks. Within three years, an astonishing 20,000 new buildings had been constructed, largely solving the housing crisis.

Medicare

Price controls aren’t confined to rental markets. Governments effectively set price controls in many markets. Consider Medicare’s experiment with aggressive price controls on durable medical equipment.

Medicare, as a big buyer, often sets the prices it will pay for equipment like oxygen machines or insulin pumps. In a push to cut costs, Medicare enacted aggressive price reductions in the durable medical equipment sector – averaging 61% cuts. Sure, Medicare saved money in the short term, but Ji and Rogers found these price caps had a dark side: innovation in those medical devices plummeted. Firms had much less incentive (and revenue) to invest in R&D. The data showed new product launches fell by 25%, and patent filings—a proxy for innovative activity—dropped a whopping 75% after the price cuts. Basically, squeezing prices so far down strangled the signal (and funding) that would normally spur improvement. Manufacturers also started outsourcing production to cheaper overseas facilities to cope, which led to higher defect rates in some devices. Lower prices, but also lower quality and less innovation—not exactly a policy triumph. It’s a prime example of how suppressing prices can undermine the very goals policymakers care about in the long run (in this case, better health tech for patients).

This is a textbook case of suppressing price signals. By artificially lowering prices, Medicare inadvertently told manufacturers: “Stop investing in better medical equipment.” When manufacturers could no longer recoup their R&D investments through prices that reflected the value of innovation, they responded rationally by innovating less.

The story doesn’t end there. Facing reduced revenue, manufacturers increasingly outsourced production to lower costs. This shift was associated with a 129% increase in adverse events reported to the FDA among outsourcing manufacturers. The attempt to control prices not only stifled innovation but potentially compromised patient safety.

Most strikingly, Ji and Rogers estimate the annual R&D expenditure losses at $2.6 billion—potentially exceeding the $3.8 billion in Medicare savings. This suggests that even purely from a fiscal perspective, the price controls may have been counterproductive in the long run by sacrificing valuable innovation.

Policy Can Create Missing Prices

The lessons on price controls above may make you think “policymakers should just leave prices alone.” In this framing, the policymakers job is to stay out of the way. That’s too simple. Policymakers can actively help prices function.

For example, for most of the 20th century, the Federal Communications Commission gave away spectrum licenses for free through what they called “comparative hearings” but what others called “beauty contests.” Companies would file lengthy applications explaining why they deserved free spectrum. FCC commissioners would then spend months or years reviewing applications before choosing winners based on vague “public interest” criteria.

This administrative approach was a disaster. It caused years-long delays in deploying new technologies. It invited political influence and corruption. Worst of all, it completely ignored the economic value of spectrum—one of our nation’s most valuable natural resources—by giving it away for free to favored companies.

Enter Ronald Coase, an economist whose 1959 paper “The Federal Communications Commission” proposed a radical alternative: auction the spectrum to the highest bidder. Let market prices determine who gets these valuable resources. The reaction was intense. When Coase presented his ideas to the FCC, one commissioner famously asked, “Is this all a big joke?” FCC officials and industry executives alike thought the idea was absurd.

The status quo persisted until 1982, when the FCC, overwhelmed with cellular license applications, tried a new approach: a lottery. Anyone could apply for a valuable spectrum license by filling out a simple form and paying a small fee. The result was predictably chaotic. Over 400,000 applications flooded in. Dentists, taxi drivers, and random citizens won valuable licenses worth millions, which they promptly flipped to telecommunications companies. The government had essentially given away billions in public assets through pure chance.

This fiasco finally created the political will to try Coase’s auction approach. But how exactly should these auctions work? Spectrum auctions present unique challenges—licenses have complex interdependencies, companies need specific combinations of licenses, and the government wants to promote competition rather than just maximize revenue.

This is where economists truly shined. A team led by economists Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson (who would later win Nobel Prizes for their work) designed innovative auction formats specifically for spectrum. They created what became known as the “simultaneous multiple-round auction,” allowing bidders to see each other’s bids and adjust their strategies as prices revealed information about others’ valuations.

The first major spectrum auction in 1994 generated $7 billion for the U.S. Treasury—far more than anyone expected—for spectrum that had previously been given away for free. But the benefits went far beyond government revenue. By allocating spectrum to those who valued it most highly, the auctions accelerated wireless innovation and deployment. Companies that won spectrum through auctions had powerful incentives to put it to productive use quickly to recoup their investments.

Since then, spectrum auctions in the US alone have generated over $200 billion in revenue while dramatically accelerating wireless innovation. Countries that moved quickly to auction spectrum saw faster deployment of new wireless technologies and greater economic benefits than those that clung to administrative allocation.

What makes this story so powerful is how it fundamentally transformed the government’s approach to a critical resource. Rather than bureaucrats deciding who “deserved” spectrum based on political criteria, they created a market mechanism that revealed its true economic value through prices. This shift from political allocation to market allocation unleashed tremendous innovation and value creation.

Governments Can Both Create and Kill Price Signals

The recent battle over New York City’s congestion pricing program provides another glimpse into the interplay of prices and politics, even when those signals are deliberately designed as policy tools.

New York City implemented a congestion pricing system in January 2025, charging drivers $9 to enter Manhattan below 60th Street. This wasn’t just a revenue grab—it was a deliberate price signal designed to communicate the true costs of driving in congested areas while creating incentives to reduce traffic, pollution, and infrastructure strain. In many ways, it was a natural extension of the spectrum auction: price something valuable that wasn’t previously priced.

Early data showed the system was working as intended. Traffic inside the toll zone dropped 9 percent compared to the previous year, with nearly 56,000 fewer vehicles entering daily. Meanwhile, foot traffic in the tolling zone actually increased by 5 percent, suggesting the pricing mechanism was effectively balancing access while managing congestion.

But President Trump’s administration has now moved to revoke federal approval of the program, with Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy citing concerns about costs to “working-class motorists.” Governor Hochul and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority have quickly filed lawsuits to preserve the program.

This political battle perfectly illustrates the tension between economics and politics when it comes to price signals. Economists might see a successful congestion charge that’s properly signaling resource scarcity and creating incentives for more efficient transportation choices. Politicians, however, see an opportunity to position themselves as defenders of consumers against “unfair” prices.

What makes this case particularly interesting is that congestion pricing represents a government-created price signal—a deliberate attempt to use market mechanisms to solve collective problems. Unlike normal prices, congestion pricing was specifically designed to communicate the social costs of driving in dense urban areas.

This represents something of a paradox: one part of the government implemented this price signal that another is now working to eliminate. The policy was created to reflect real costs that the market wasn’t naturally capturing, only to be dismantled because acknowledging those costs is politically unpopular.

This highlights a crucial reality: rejecting a price signal doesn’t eliminate the underlying costs—it merely redistributes or conceals them. By removing congestion pricing, these costs don’t disappear; they simply shift:

Working With Price Signals, Not Against Them

None of this means we must accept every painful price spike without action. But effective policies work with price signals rather than against them.

Price signals aren’t just information for market participants—they’re vital feedback for policymakers themselves, even if policymakers don’t have the direct profit incentive to fix the problem. They still get some signal. When housing prices in coastal cities surge to multiples of the national average, that’s not just information for builders and consumers—it’s a powerful signal to local officials that their land-use regulations are creating artificial scarcity.

When confronted with high prices, policymakers face a fundamental choice: should they suppress the price through regulation, or should they increase supply, or should they allow the price to remain high? The answer depends on correctly diagnosing the cause. The first question isn’t “How do we make this cheaper?” but rather “Why is it expensive in the first place?” Many policymakers are concerned about housing prices. Rather than capping rents (which would mask the price signal), are high prices signaling a regulatory problem? Can policy reduce the true cost of building, which lowers prices and increases quantity? This would shift the supply curve down. This is different from making housing look cheaper through a subsidy that does nothing to the underlying scarcity. The subsidy would shift the demand curve up, driving up prices. This distinction—between treating prices as problems to be regulated away versus information about what needs fixing—often separates policies that work from those that backfire.

Similarly, when Texas electricity prices soared to $9,000 per megawatt-hour during the 2021 winter storm, those astronomical prices weren’t just signals for consumers and generators—they were critical information for regulators about infrastructure vulnerabilities. The price spike revealed the true cost of the state’s isolated grid and inadequate weatherization standards, information that would have remained hidden under a price cap. While Texas officials initially misread this signal by blaming market manipulation rather than infrastructure failures, the price mechanism did reveal the enormous value of system reliability.

Price suppression is particularly destructive because it creates a feedback loop of political failure. When politicians cap prices, they lose the information that would reveal whether their policies are working. This information blackout makes course correction nearly impossible—without accurate signals about scarcity, how can officials tell if their supply-side interventions are sufficient? The result is often a spiral of increasingly heavy-handed interventions trying to fix problems that the officials themselves can no longer properly diagnose.

The most successful policy approaches maintain clear price signals while using other tools—targeted subsidies, infrastructure investments, or regulatory reforms—to address distributional concerns. This preserves both the information and incentive functions of prices while acknowledging that markets alone may not achieve all social goals. By working with price signals rather than against them, policymakers not only enable more efficient markets but also gain the feedback they need to craft more effective policies.

Price signals aren’t perfect. They can be distorted by market power, externalities, or incomplete information. But they remain our most powerful tools for coordinating economic activity, and policies that ignore their dual nature as signals and incentives typically create more problems than they solve.

This rejection of price theory isn’t just intellectually mistaken—it’s practically harmful. When we ignore price signals, we’re flying blind. We lose our most important feedback mechanism for allocating scarce resources efficiently. We substitute the dispersed wisdom of millions of market participants with the limited knowledge of a few policymakers, no matter how well-intentioned.

So the next time you see politicians vilifying “high prices” without addressing underlying causes, remember: those prices are messengers. Shooting them won’t solve our problems—it will just leave us in the dark. The economic insights that guided policy for decades haven’t stopped working just because they’ve become politically inconvenient.

As I said, all of the other insights from economics for policy depend on understanding prices. In the next installment of this series, I’ll explore another fundamental economic insight: demand curves slope downward. Stay tuned.

Brian, thanks for a good article. May i make a couple of points?

For me the information value is much higher when you get into the meat of the subject with excellent examples to illustrate. The earlier explanatory section would benefit from some editing, but this depends on your readership.

There is a gap however: where is the section on government subsidies to influence price signals which you mention at the end? Did i miss something? This makes the essay seem to me unbalanced and could be seen as a blind spot.

Hope this assists your work which i appreciate greatly. Lawrence from London

Thank you for this excellent article. I have never read prices explained in such a simple way while studying economics. Economists and politicians try to act as if gaining control over prices would solve all economic problems. Important reminder on the value of prices.