You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 12,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Wendy’s is in hot water after suggesting it may implement “dynamic pricing”—charging higher prices during peak demand times. The backlash was swift, with accusations of profiteering and calls for consumer boycotts. Wendy’s quickly backpedaled, insisting they would not be raising prices when wait times are longest.

This minor PR crisis illuminates the complex love-hate relationship modern consumers have with dynamic pricing. We’ve grown accustomed to paying high last-minute airfares and late-night, drunk Uber rides. But dynamic pricing also triggers perceptions of unfairness that can erode brand trust.

As (probably) the only newsletter that writes about Wendy’s and price discrimination, I couldn’t let this news story pass without reminding readers about a few things.

Is it price discrimination or just supply and demand?

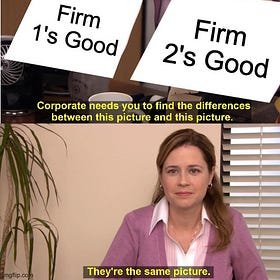

We need to distinguish dynamic pricing from price discrimination, since the two terms are thrown around with this story.

I’m not sure there is an agreed-upon definition, but I define price discrimination as charging different prices for goods that are identical from the seller’s perspective. (We could imagine consumers price discriminating, but we will focus on the seller doing it.) What makes the two goods identical? That’s not so clear since value is subjective but as an approximation, we can think of them as having the same cost to the seller. For example, seniors and student discounts discriminate based on consumer willingness-to-pay, not cost differences.

Dynamic pricing, on the other hand, entails adjusting prices over time. This could be in response to cost changes or because the consumers change over time. In other words, sometimes dynamic prices are just about shifting supply and demand, while at other times, dynamic pricing can be an attempt to price discriminate.

The distinction between competitive pricing and price discrimination is not always clear-cut in practice. A simple example is pricing differences for haircuts based on gender. On the surface, the common practice of charging women more than men for haircuts appears to be price discrimination. The service rendered is essentially the same—cutting and styling hair—regardless of gender. The time and effort involved does not necessarily differ systematically by gender.

However, clearly the costs are somewhat different, at least in expectation. Cutting and styling longer hair, more typical of female customers, takes more time and labor. So the pricing variation reflects dynamic elements like cost fluctuations based on service duration and complexity. Is that the whole story? Probably not. In practice, it is probably a bit of both, neither purely based on costs nor purely price discrimination.

Is price discrimination bad?

The usual perspective is that charging different prices based on costs is fine. That’s just supply and demand. If tons of consumers arrive exactly at 12:00 for lunch, the workers have to work harder to make all the meals in the time consumers expect. “Work harder” is another way of saying it is a higher cost to produce the good “burger in 2 minutes.”

In contrast, people often think price discrimination is bad and unfair. While not always a good thing (I’ll say more below), I’m a strong proponent of more price discrimination on the margin.

There are two reasons to want more price discrimination. First, price discrimination increases profits and producer surplus. All else equal, that’s a good thing. Profits are a sign of turning low value into high value. Those profits lure investment, cover fixed costs, and increase output.

Monopolies don't make enough money

Building on last week's theme, thanks Josh, I want us to think about counterfactuals today—that dreaded, "compared to what?" we economists harp on. Instead of focusing on the first model taught in undergrad, I want to jump all the way to the second model: monopoly. 🤯

But suppose you only care about consumer surplus. Can price discrimination by sellers be a good thing?

First, consider a single firm using the information to price discriminate and compare to a fixed price where all consumers receive the same price. Yes, the firm can use the information to raise prices for people willing to pay more. That hurts those consumers.

However, it is often forgotten that price discrimination lowers the marginal cost for the marginal consumer. The firm selectively lowers prices for consumers who would not purchase with a fixed price. That second effect unambiguously helps consumers.

This is the effect we see stressed in practice. While Wendy’s has now said it “would not raise prices when our customers are visiting us most,” it could still be willing to drop prices when consumers aren’t visiting. That’s literally the same thing, but the PR spin is different. Coupons are okay. Surge pricing is bad.

By dropping prices for some consumers, price discrimination can also lead to increased quantity available. We know that, in general, total surplus (consumer benefits plus firm benefits) increases whenever price discrimination leads to a quantity increase.

But that’s not the end of the story. We should never forget competition. All of these firms are competing. With multiple sellers competing and trying to price discriminate, the benefits of price discrimination for consumers become more likely. Price discrimination can benefit consumers, even without increasing the quantity sold in a market. When the firms learn that customers are more price sensitive, the level of competition increases and drives down prices more than when there is no price discrimination.

In fact, my own papers show a simple example where perfect price discrimination maximizes consumer surplus. The reasoning from a single seller doesn’t extend neatly to multiple sellers, as I’ve pointed out before.

What the Heck is Welfare?

With it being the holidays, I thought we should talk about the basics of welfare economics. I hope the refresher is helpful and allows us to avoid some confusion. First, a bit of “background”: Bryan Caplan wrote a post on price discrimination, a favorite topic of mine

The important thing is not to say price discrimination always helps consumers; it does not. Instead, one must recognize that price discrimination can help consumers, and this is not a super weird outcome but a standard outcome of many economic models.

Ultimately, it is an empirical question and not merely a theoretical curiosity. Many studies find that some benefits from more price discrimination. In a study from Kehoe, Larzen, and Pastorino, using eBay data, when sellers are able to use “detailed information on individual web-browsing and purchase histories” that was previously unimaginable for sellers, “a significant fraction of consumers are better off under price discrimination relative to uniform pricing, as price discrimination intensifies competition for each individual consumer.” In another paper, using a randomized control trial of a large digital firm, Dube and Misra find that “While total consumer surplus declines under personalized pricing, over 60% of consumers benefit from personalization” of prices. And this is just consumers benefits and not looking at the dynamic benefits I mentioned before—the allure of more profit increases investments and innovation.

Why haven’t we seen more dynamic pricing already?

With the expanding ability to segment consumers and adjust pricing digitally, one might expect dynamic pricing to be ubiquitous already. However, outside limited contexts like ride-sharing and travel, variable demand-based pricing remains modest. Why?

As Josh has pointed out before, brand reputation and customer loyalty impose constraints:

Raising prices to capture the extra surplus during a busy Friday night might lower future demand from customers who would have tried the restaurant at a lower price and become a loyal customer or from customers they lose to search. One might therefore think of the foregone surplus today as an investment in customer loyalty that produces a higher present discounted value of future demand.

Why Price Gouging Laws Aren't So Bad

Macroeconomists seem to be pre-occupied with sticky prices (the idea that prices adjust slowly to “shocks”). In fact, the existence of sticky prices is the main difference between the real business cycle model I discussed in my initial post and the New Keynesian model that serves as the workhorse of a lot of monetary policy research. However, most macro…

Dramatically raising prices during peak periods risks alienating buyers and eroding trust. Loyal customers who find alternatives may permanently switch away. Most sellers care about maintaining stable long-term relationships, not maximizing revenue in isolated transactions. As Josh summarized: “Firms care not just about the level of demand at a moment in time, but also the present-discounted value of future demand from loyal customers.”

Maintaining trust around consistent pricing proves more valuable than fully capitalizing on fleeting demand spikes. Without that stability, customers incur search costs trying to deduce fair pricing each time conditions fluctuate. So companies hesitate to adopt widespread dynamic pricing given branding risks, despite growing technical feasibility. The benefits of enduring buyer relationships impose discipline and pricing restraint.

It’s a balancing act that each firm is trying to navigate. As always, there needs to be room for experimentation in markets. Firms need to be free to make choices that may backfire and piss off consumers. That’s how change happens.

I’ll conclude with a bold statement: the optimal amount of dynamic pricing is somewhere between zero and constantly adjusting. As the cost of dynamic pricing decreases with technology, the optimal amount increases on the margin.

Let’s see more dynamic pricing!

Hi Brian,

Long-time reader, first-time commenter. This is an interesting piece in defense of dynamic pricing. Do you think that part of the appeal (and the way customer trust is earned) comes from predictable pricing? Some of that predictable pricing will be influenced by a Wendy's franchise's "reserve capacity." If customers think that dynamic pricing will affect predictable pricing (whether or not it actually does) there's bound to be a decline in trust and customer backlash.

Even in the case where customers may pay less for a meal during "off peak" hours than under the status quo pricing model, they would still prefer the predictable pricing over variable pricing.

I'm reminded of this passage from Universal Economics:

"Customers are willing to pay a slightly higher price, which covers the cost of unsold copies [of newspaper], in order to have immediate availability at a predictable price. The cost of inventories may result in a smaller paper or fewer retail outlets, but this will result also in a lower full cost/price to consumers than will the other options. Thus, a third reason for inventories is that they help a seller maintain stable, reliably predictable prices despite minor fluctuations in demand and supply, thereby helping customers plan their shopping." (Alchian, Armen and Allen, William. Universal Economics. Liberty Fund, 2018, pp. 146-147.)

Would love to hear your thoughts about this!

Good thing I decided to stick with my normal post for Monday because I was about to write about this one