A Data-Driven Case for Productivity Optimism

Noah Smith of Noahpinion generously offered to send this week’s newsletter to his subscribers. Make sure to check out the rest of his writing and subscribe.

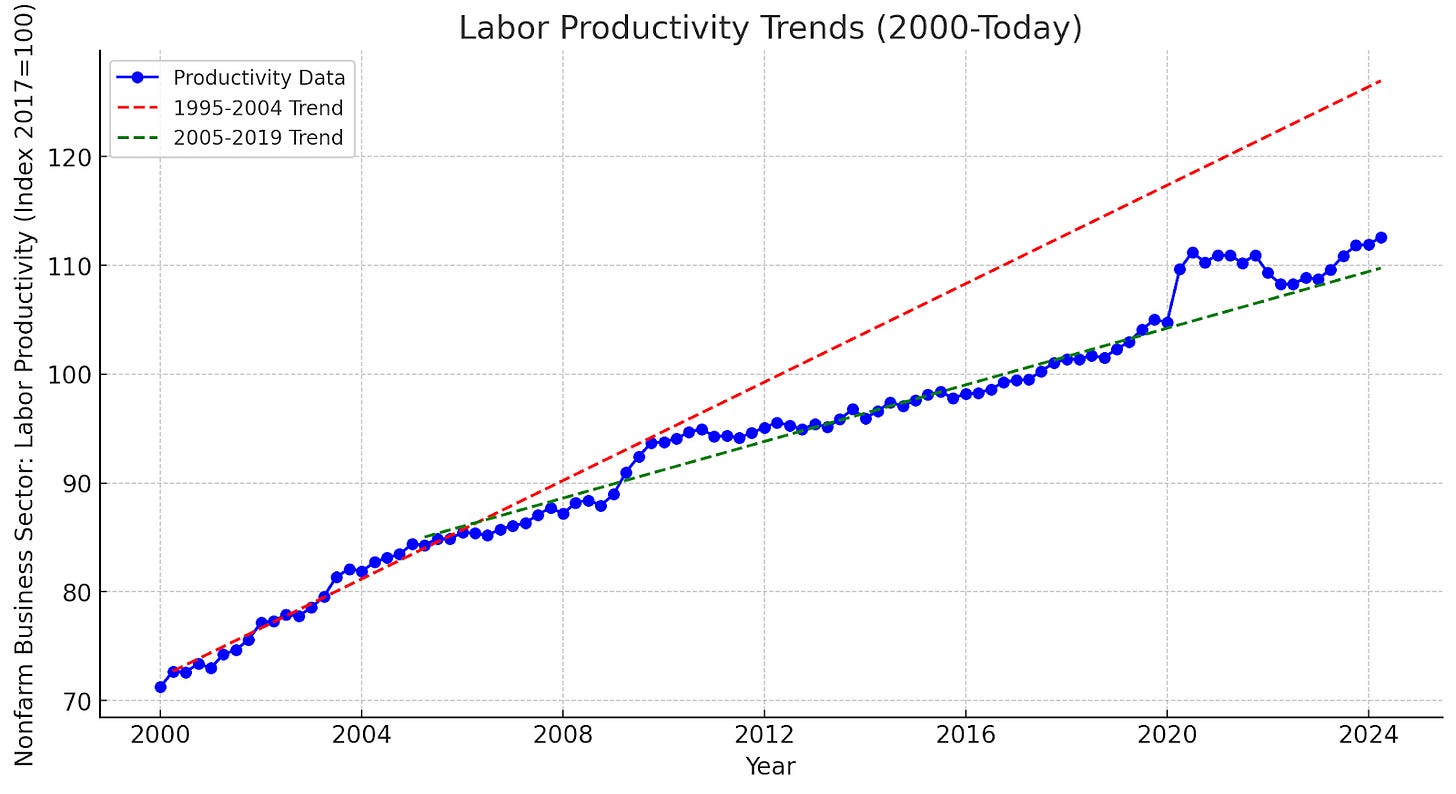

Wall Street gets worked up over each jobs report or move by the Federal Reserve, but Main Street’s prosperity hinges on a less flashy metric: productivity growth. For nearly two decades, America’s economic engine has been sputtering, with labor-productivity growth crawling at just 1% annually, down from the more than 2% growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This decline has cost the average American household around $10,000 per year in income.

The latest numbers offer hope—U.S. labor productivity grew 2.3% annually in the second quarter of 2024, pushing the yearly gain to 2.7%. But this recent surge only moves us a blip above the disappointing 2004-2019 trend. We’ve climbed out of the pandemic-induced volatility only to find ourselves back on a path of underwhelming productivity growth.

Despite this gloomy picture, a broader look at the economy offers reasons for optimism. Over at Noahpinion, Preston Mui offered a cautiously optimistic view on the potential for a resurgence in productivity growth, drawing parallels to the macroeconomic conditions of the 1990s: full employment, a boom in fixed investment, and a stable supply side. My optimism comes from three different sources: recent momentum, America’s enduring competitive advantage, and technological change.

First, the momentum. While the volatility of the pandemic economy ultimately landed us back on the sluggish trend, the past year has seen solid productivity growth. If sustained, this could mark the beginning of a new, more robust trend. It’s too early to declare victory, but the signs are encouraging. Moreover, the recent preliminary revisions to payroll data will ultimately work their way into a downward revision of the hours worked. If next month’s NIPA revisions do not change our output measures too much, the same output from fewer hours worked will bump up measured productivity. The exact revision will be more complicated than Dean Baker’s quick calculation that the 0.5% revision to payrolls will amount to a 0.5% percent increase in productivity. However, that gives you a sense of the magnitude we could see.

Second, for all the hand-wringing about declining competition, the U.S. remains competitive. Carl Shapiro, former Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economics at the DOJ under Clinton and Obama, and Ali Yurukoglu recently provided the most comprehensive survey. They argue, “We explain that the empirical evidence relating to concentration trends, markup trends, and the effects of mergers does not actually show a widespread decline in competition… [I]n many respects the evidence indicates that the observed changes in many industries are likely to reflect competition in action.”

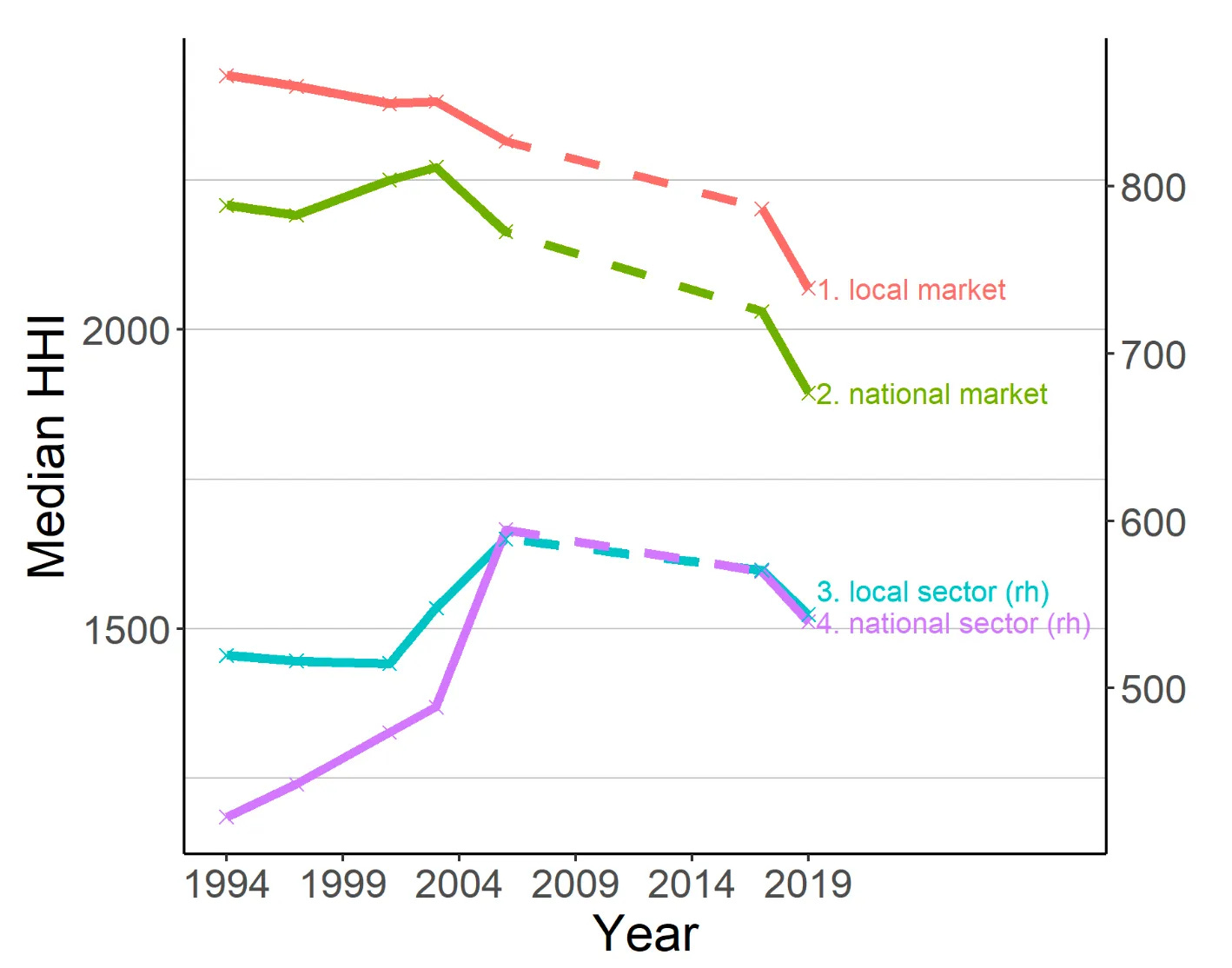

For example, the most common measure of competition is concentration. While concentration metrics based on broad industry classifications have increased in recent decades, more careful work paints a different picture. Benkard et al. measured concentration using narrower, more economically relevant product market definitions. They found that concentration levels in many consumer “markets” are actually declining, compared to the broader sectors..

Or if you take local and import competition seriously, as Amiti and Heise do, since consumers can choose between both, “U.S. market concentration in manufacturing was stable between 1992 and 2012.” That’s just for manufacturing, but that is where we have data on imports.

If you, like me, don’t like concentration as a measure of competition, a comprehensive look at data on market power also does not suggest a fall in competition. First, the headline-grabbing numbers from De Loecker, Eeckhout, and Unger about rising markups are subject to enough critiques to not be the final word. If you look at in-depth industry studies as a whole, as Nathan Miller, an IO economist who will soon be joining the DOJ’s antitrust division, has done, you’ll tend to find that rising markups often result in falling prices—a clear indicator of robust competition. In fact, my own recent research with Ryan Decker found that industries with larger increases in markups have actually seen smaller declines in dynamism, suggesting profits are luring new entrants in, as economic theory suggests, but counter the common doom and gloom narratives about market power in the U.S.

Most importantly for productivity, the U.S. remains a leader in directing resources to its most productive companies—my preferred measure of competition. In the U.S., efficient firms win consumers; that’s not true everywhere else, where size is more determined by things like political favoritism. This competitive reallocation is a key driver of productivity growth that sets the United States apart from its peers. This process of creative destruction is vital for long-run productivity growth and innovation.

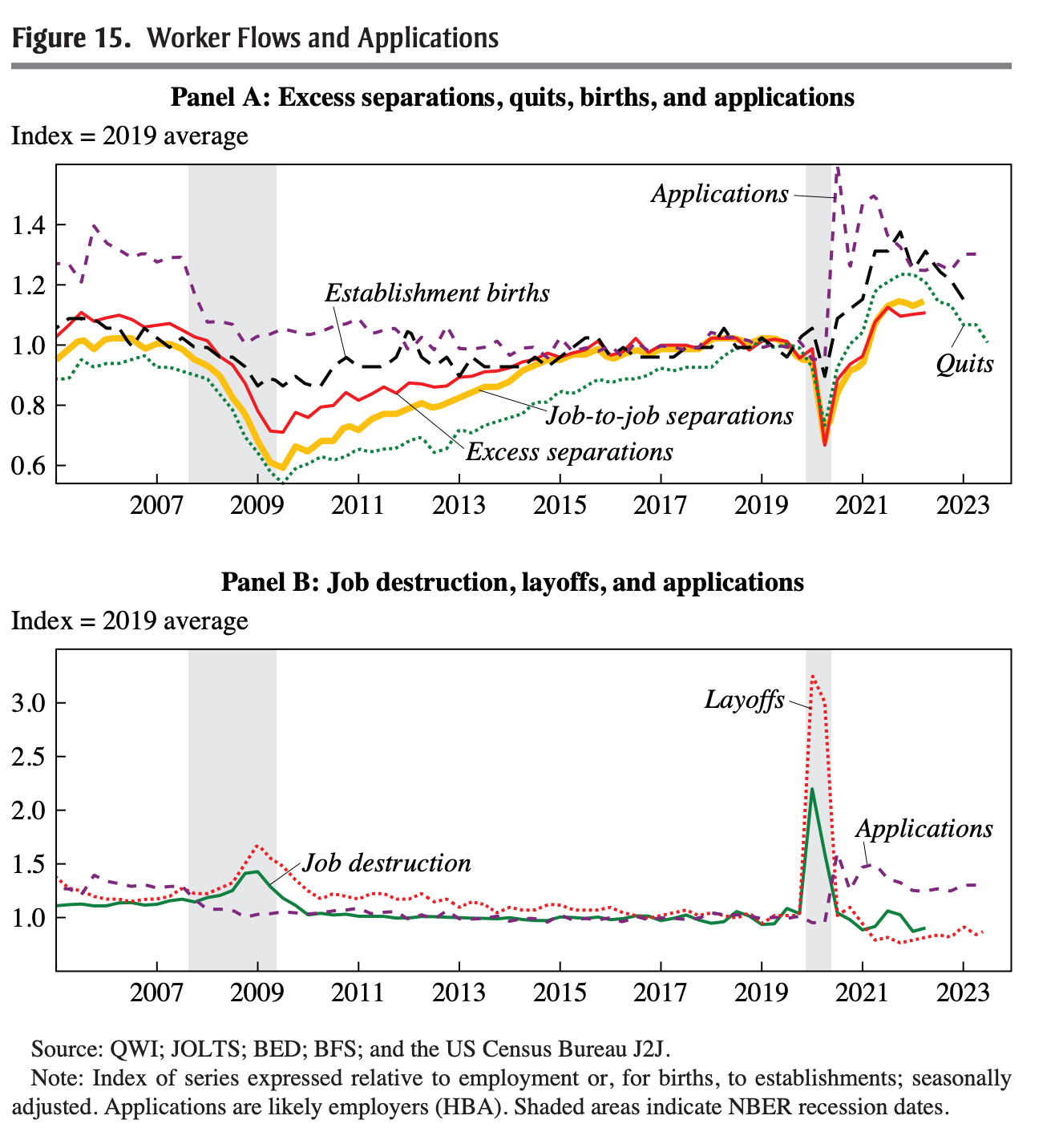

It is well documented that business dynamism slowed from the mid-90s until COVID hit. However, recent data suggests a change for the better. Ryan Decker and John Haltiwanger found a surge in new business formation, especially in high-tech industries. But we’re also seeing increased formation in sectors like restaurants, construction, and building services. These trends bode well for future productivity growth. New firms are jumping in with fresh ideas, forcing the old guys to innovate or get left behind.

In addition to business formation, we’ve seen increased labor-market churn, with more workers voluntarily switching jobs—a sign of a healthy, competitive economy. One measure of worker dynamism and churn is “excess separations.” To understand excess separations, think of it this way: when workers leave their jobs, it’s either because the job itself is disappearing (like when a company is downsizing or shutting down a department) or because the worker is moving on to a different opportunity while the job remains. In the first case, the worker leaves, and the job vanishes too—this is a straightforward job loss with no excess separations. However, in the second scenario, the worker leaves, but the job is still there and will be filled by someone else. This is an “excess separation.” In a recent Brookings paper, Decker and Haltiwanger show this number was elevated above pre-pandemic trends. Other measures of labor market dynamism, like job creation rates and job destruction rates, were elevated too, although still nowhere near their peak at the end of the 1990s. Most of these labor measures have cooled back down, so it is not all rainbows and sunshine. But even the temporary upturn in dynamism could help kickstart the productivity boom.

Taken as a whole, the competitive dynamism in the U.S. economy can only explain why, over the long run, we shouldn’t expect productivity slowdowns to persist indefinitely. Never bet against America in the long run. The ability of the American economy to reallocate resources to more productive firms and encourage innovation through competitive pressure creates a natural tendency towards productivity growth over time. We can think of that as driving the trend. But competitiveness doesn’t explain why we might see an above-trend uptick in productivity growth over the medium term.

This brings us to the third reason for optimism: we are on the verge of an AI-driven boom. The U.S. economy’s ability to move workers and resources around is especially powerful when new technologies emerge.

Now, I’m not talking about some AI utopia where we all quit our jobs and let the robots take over. But the data suggest we could get back to the kind of productivity growth we saw during the IT boom of the late ’90s and early 2000s, as Preston Mui suggested as well.

To be clear, the progress isn’t about chatbots. Instead, it’s about small improvements across every sector of the economy. It’s the human resources manager using AI to sift through resumes more efficiently, the logistics planner optimizing delivery routes in real-time, or the data analyst automating report generation. These minor advances, multiplied across millions of workers and thousands of businesses, are what will ultimately drive significant productivity gains.

The computer revolution offers a helpful parallel. In 1987, Nobel laureate Robert Solow famously quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” This “productivity paradox” persisted for years. It’s almost comical now to think of 1987—when the original Macintosh was brand new, and C++ was just gaining traction—as an era when “the computer age was everywhere.” Even then, the transformative potential of computers was clear to many observers.

Despite the invention of the personal computer in the 1970s, we didn’t see significant productivity gains until the late 1990s. Why? It took time for businesses to figure out how to use computers effectively, redesign workflows, and develop complementary innovations. That’s why we first saw the boom among IT producers. Think Microsoft, Intel, and Dell. Only later was there a boom from companies that used IT to increase productivity, such as Walmart or Charles Schwab.

We may be at a similar juncture with AI. Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson suggest that one reason we haven’t yet seen the revolution is that our current productivity statistics understate the true gains from AI adoption. When firms invest heavily in new technologies like AI, they often incur significant upfront costs. These take the form of investments in intangible assets—things like reorganizing workflows, training employees, and developing new business processes. Our current productivity measures only partially capture these investments. In the early stages of adopting a new technology, we might see a paradoxical effect. Firms invest heavily in something that should boost productivity, but our statistics show little or no improvement. Only later, when these investments bear fruit, do we see measurable productivity gains in our official statistics.

Their analysis suggests this AI bump could have been significant already back in 2017. We could be understating current productivity growth by as much as 0.5% of GDP because of mismeasured AI investments alone. That may not seem like a radical transformation, but it would bring us closer to the 2-3% annual productivity growth we saw during the IT boom, rather than the 1% we experienced pre-pandemic.

Technology doesn’t simply fall from the sky and automatically make us more productive. If that were true, everywhere would have seen the productivity uptick already. But they haven’t.

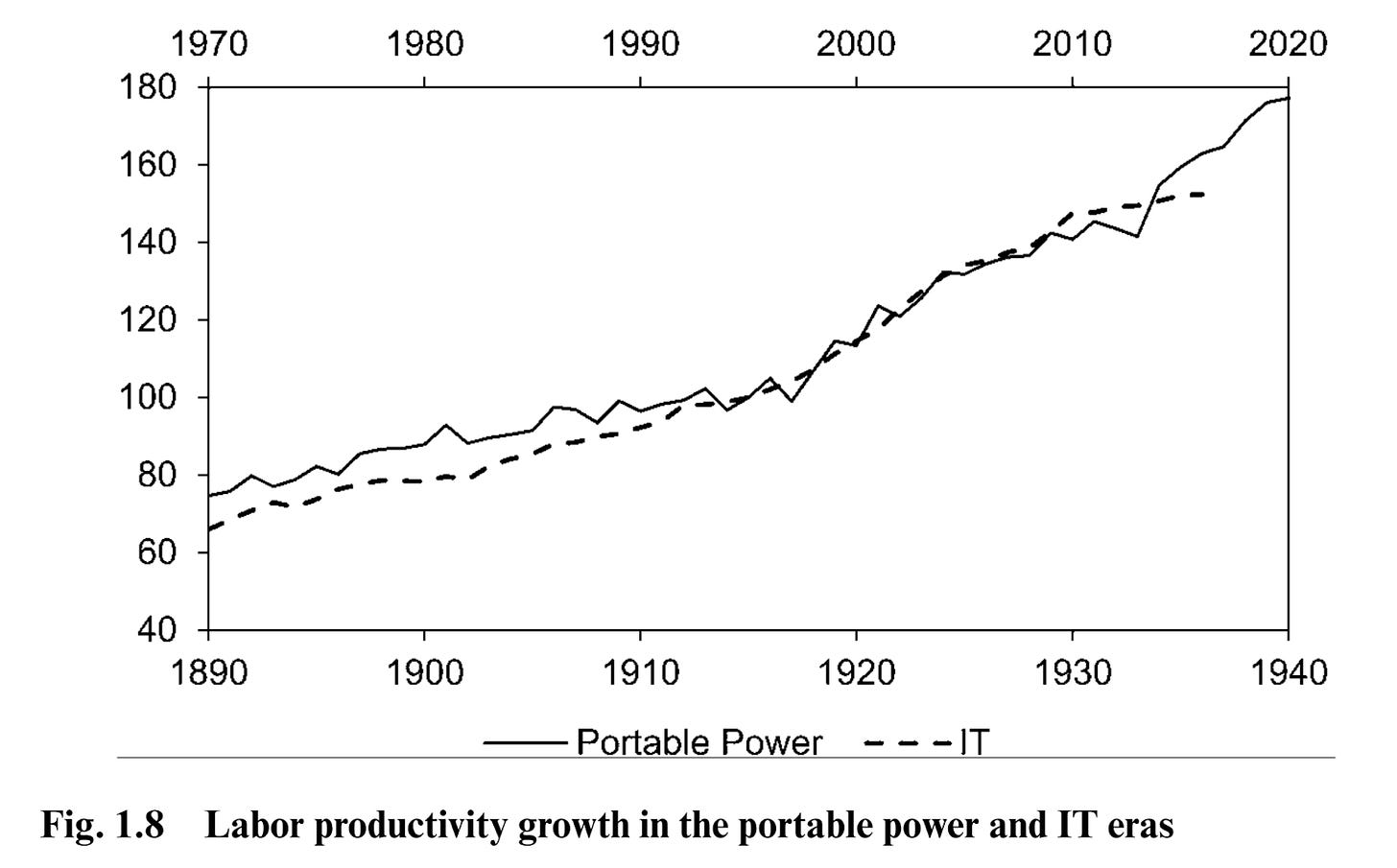

The mere existence of a technology in the world doesn’t guarantee it can actually help people produce goods and services. Rather, new technologies need to be incorporated into existing business processes, integrated with other technologies, and combined with human expertise. This process isn’t unique to AI or even computers. Historically, it took decades for businesses to fully harness the productivity potential of portable electric power. Initially, factories simply replaced their central steam engines with electric motors, missing out on the transformative potential to redesign entire production processes. It wasn’t until firms reimagined their operations around the flexibility of electric power that we saw dramatic productivity gains. In a different paper, Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson provide evidence for this in the productivity statistics. The productivity uptick only happened roughly 20 years later for both IT and portable power.

When we take seriously the need to rearrange—or should we say reallocate?—resources throughout the economy, this is where America’s competitive advantage becomes even more critical. As I said, the U.S. economy excels in developing new technologies and at integrating these innovations into real-world business operations. Our market allows for rapid experimentation, learning, and adaptation. Firms that successfully incorporate new technologies can quickly gain market share, while those that lag behind face pressure to improve or risk being left behind. This process of creative destruction, powered by our competitive markets, ensures that productivity-enhancing technologies spread through the economy more rapidly and effectively than in less dynamic markets. In essence, America’s economic dynamism acts as an amplifier for technological innovations like AI, potentially accelerating their impact on overall productivity growth relative to the rest of the world.

Of course, challenges remain. The productivity slowdown of the past 20 years was real, and its causes are not fully understood. Still, the broader economic data, not just blind optimism, increasingly point to a productivity resurgence. While it’s too early to declare victory over the productivity slowdown, there’s ample reason for optimism about America’s economic future.

Excellent

Excellent analysis; time will tell!