Will a recession raise productivity?

Probably not. But, historically, U.S. recessions often have.

You are reading Economic Forces, a free weekly newsletter on economics, especially price theory, without the politics. Economic Forces arrives weekly in the inboxes of over 19,000 subscribers. You can support our newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Recessions are painful times—job losses, shuttered businesses, and general hardship. Yet, in the current world where up is down and left is right, a counterintuitive idea has returned: that a recession might actually benefit the economy in the long run. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick recently defended the Trump administration’s protectionist policies, saying they’re “worth it” even if they trigger a downturn.

Others have floated the idea of a short detox period for the economy or even an “orchestrated recession,” a deliberate cooldown engineered through policy, with the promise of stronger growth afterward. In their view, a dose of short-term pain could purge inefficiencies, tame inflation, and set the stage for a healthier economy. President Trump himself has spoken of a “period of transition” that would ultimately “bring wealth back to America,” implying some short-run pain for long-run prosperity.

Such rhetoric taps into a long-standing idea in economics: that recessions might serve a “cleansing” function for the economy. According to this view, a downturn could purge inefficient firms, free up resources, and boost productivity as the economy recovers leaner and stronger.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the notion that recessions might have any sort of silver lining became deeply unfashionable. The Great Recession left such deep scars—millions unemployed, trillions in wealth destroyed, a slow and uneven recovery—that most economists and policymakers rejected any suggestion that downturns could be cleansing.

Before dismissing this as pure political spin, we should recognize that the post-2008 conventional wisdom may have overreacted. The cleansing hypothesis isn’t obviously wrong in all cases; it just doesn’t apply uniformly across all types of recessions. Research shows that some recessions, particularly those before 2008, did exhibit productivity-enhancing properties. The Great Recession was an outlier in many ways, not a template for all downturns. Understanding when and how recessions might improve productivity (and when they clearly don’t) is essential for evaluating claims about “beneficial” downturns.

Cleansing vs. Sullying

The idea that recessions might have an upside dates back to Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction. In booms, inefficiencies accumulate. bloated firms survive on easy credit, marginal workers stay employed, and zombie companies limp along. A recession forces a reckoning: weak firms fail, resources are released, and when growth resumes, those resources flow to more productive uses, raising the economy’s overall efficiency. Austrian business cycle theory has a similar mechanism.

This cleansing effect has more recent theoretical backing. Caballero and Hammour formalized conditions where recessions lead to more intense reallocation that disproportionately moves resources toward higher-productivity firms. Their model suggested that when the opportunity cost of resources is low (as in a slump), it becomes easier for high-productivity firms to expand while low-productivity ones contract or exit. They then used this model to analyze U.S. manufacturing job flow data from Davis and Haltiwanger, showing that job destruction is significantly more cyclical than job creation, a pattern consistent with recessions accelerating the exit of less productive firms.

The cleansing hypothesis rests on the idea that recessions intensify market selection. In boom times, even less efficient firms can survive, buoyed by strong demand and possibly readily available credit. A downturn removes this cushion. Falling demand exposes the relatively weak business models. This forces a shakeout: the least productive firms, those with higher costs or lower value-added, are disproportionately likely to shrink or fail. Firms exiting (which mechanically raises measured average productivity but doesn’t make the economy as a whole more productive) is not the cleansing effect. I’ll say more about the mechanical effect below.

The true productivity gains, the cleansing, come when a high-cost firm exits and releases resources, such as skilled labor and physical capital. The core idea is that these resources then become available to the more productive firms that weather the storm, enabling them to expand and improve the economy’s overall productivity once recovery takes hold. In the extreme example, all of the old resources are back employed. The gains aren’t from firing the least productive workers. But when the dust has settled, we have workers at more productive firms. That’s a true gain to productivity.

But there’s a flip side to the cleansing theory. Recessions can also have what economists call a “sullying effect,” where tight credit and scarce jobs prevent the usual processes of creative destruction. When credit is tight, even good businesses might be starved of funds. Talented workers might cling to less productive jobs, unable to find better matches. In this view, recessions impede the reallocation of resources to their best uses.

If Caballero and Hammour is the key citation for the cleansing effect, Gadi Barlevy has the paper on the sullying effect, aptly called “The Sullying Effect of Recessions.” During recessions, fewer workers quit or switch jobs voluntarily, meaning bad job matches persist longer. In boom times, a worker in an unproductive role can easily find a better job; in a bust, they hang on, and firms hesitate to replace them. This sullying effect implies the quality of worker-firm matches may decline in a recession, dragging on productivity.

In another paper, Barlevy also focused on the role of credit. If firms need external financing to grow or survive, a credit crunch can hit the most productive firms hardest, because the best projects often require the most capital. In his model, the best jobs will be destroyed in a recession when credit is scarce, as innovative firms can’t fund operations, while some less productive firms might survive by inertia.

The core question, then, isn’t just whether cleansing or sullying happens but which force dominates and under what conditions. Aggregate productivity growth reflects the net outcome of these competing dynamics. If the cleansing effect is strong and the economy is effectively reallocating resources freed up from failing firms to more productive, growing ones, overall efficiency can rise post-recession. But if the sullying effect prevails with credit crunches paralyzing good firms and labor markets freezing up, preventing good matching of workers and firms, then the downturn might destroy productive capacity or impede resource mobility more than it cleanses, leading to a net decrease in efficiency. Understanding this balance and how it varies across different types of recessions is key to evaluating whether any specific downturn could, even theoretically, leave the economy stronger.

Empirical Questions Need Data

While Caballero, Hammour, and Barlevy built compelling theoretical frameworks about cleansing and sullying effects and used the best data available, their work largely preceded the explosion of granular data on firm dynamics and productivity. Debates remained somewhat abstract until recent years when economists gained access to comprehensive datasets covering millions of U.S. businesses.

I’ve written before about how John Haltiwanger and his collaborators have revolutionized our understanding of productivity through their work with Census Bureau microdata. Rather than relying on aggregate statistics, they can actually observe what happens inside firms during booms and busts, tracking employment, productivity, and reallocation with unprecedented detail.

This firm-level approach allows them to answer fundamental questions: Do more productive firms actually fare better in recessions? Does labor flow to its most productive uses during downturns? How does the pattern of job creation and destruction change in crisis versus normal times?

The Census Bureau datasets are particularly powerful because they cover the entire economy, not just publicly traded companies, but also small firms and new entrants that often drive innovation and dynamism. In a recent paper, they link individual workers to their employers, allowing researchers to track job changes, wage patterns, and productivity relationships over time. With this data, they can directly measure productivity differences between firms and see how resources shift in response to economic conditions.

In their 2016 paper, Foster, Grim, and Haltiwanger analyze establishment-level data across multiple recessions from the 1980s through 2009. They find that in a typical pre-2007 recession, reallocation intensified and became more productivity-enhancing. When unemployment rose, the gap between high-productivity and low-productivity firms’ growth rates would widen. The efficient firms would continue expanding (or contract less) while the inefficient ones faced steeper declines. This pattern supports the cleansing hypothesis: downturns did seem to accelerate the natural selection of efficient firms over inefficient ones.

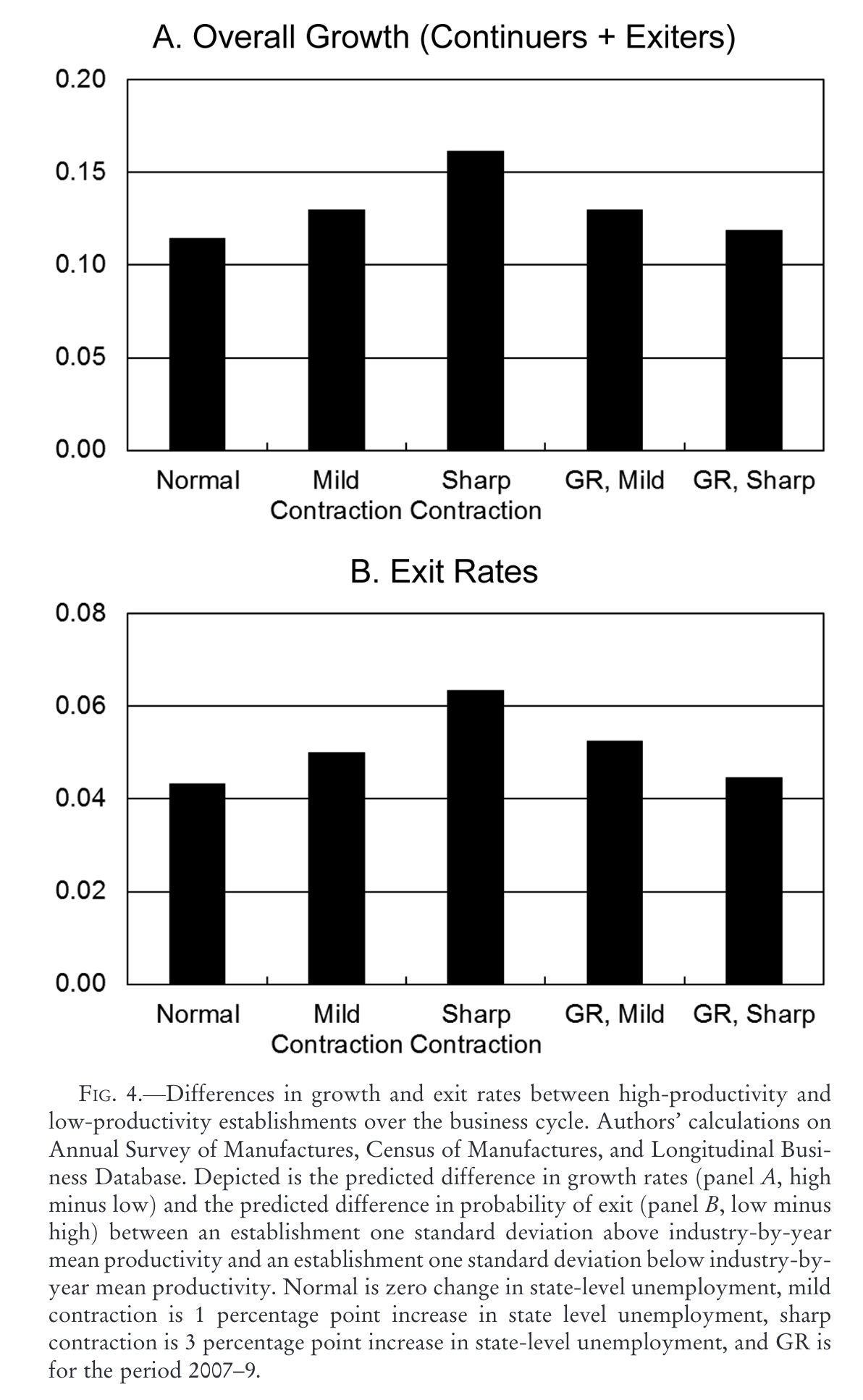

Let’s look at the figure below, especially the first three bars. The data show that before 2007, a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate (a mild contraction) would widen the growth rate differential between high- and low-productivity establishments by several percentage points. In concrete terms, if unemployment jumped from 5% to 6%, a factory in the bottom quintile of productivity might see its employment shrink by an additional 3-4 percentage points compared to a factory in the top quintile. This differential sorting effect became stronger as recessions deepened, suggesting that more severe downturns had stronger cleansing effects. In sharp contractions (defined as a three percentage point increase in unemployment), the gap grew even larger.

The Great Recession: A Special Case

What made the post-2008 narrative so anti-cleansing was that the Great Recession broke many of the normal patterns of recessions and productivity. Foster, Grim, and Haltiwanger show that while earlier recessions (like those in the 1980s and 1990s) did exhibit some productivity-enhancing reallocation, the Great Recession was markedly different.

Perhaps most importantly, the firm-level evidence reveals that not all recessions follow the same script. The 2008-09 downturn broke the historical pattern in crucial ways. Unlike previous recessions, where reallocation intensity increased, the Great Recession saw the pace of job reallocation fall to historic lows. The establishment-level data shows job creation rates dropping to the lowest levels in over three decades. Even though job destruction increased (as expected in a recession), the collapse in creation was so severe that total reallocation activity actually declined.

In previous downturns, high-productivity firms would typically continue to grow (or shrink much less) compared to low-productivity peers; the gap in their growth rates widened during recessions, indicating cleansing. During 2007-09, that gap actually narrowed. High-efficiency businesses, like everyone else, were fighting for survival rather than capitalizing on others’ weaknesses.

The intensity of reallocation also fell to historically low levels in 2008-09. Job creation dropped so dramatically (to the lowest in 30 years) that overall churn was subdued. In previous recessions, even though job creation declined, job destruction spiked enough that total reallocation stayed high. In 2008-09, job destruction jumped, and job creation collapsed, leading to very low overall reallocation.

While low-productivity establishments still contracted more than high-productivity ones, the gap narrowed significantly compared to historical patterns. The figure above from Foster, Grim, and Haltiwanger shows the growth differences between high- and low-productivity firms. In other sharp contractions, that gap is normally high. But in the Great Recession (GR), that gap dropped, especially at the sharpest part of the contraction.

The microdata approach offers a definitive perspective on whether recessions boost productivity. Rather than debating hypotheticals, we can now trace the actual paths of workers, jobs, and businesses through different types of economic cycles, revealing when recessions might have beneficial cleansing effects and when they simply destroy economic capacity without compensating benefits.

Why was 2008 different? The study points to distortions like credit market failures. The financial crisis was a perfect storm. Many young, innovative firms suddenly couldn’t get loans or investment; consumers pulled back across the board; and uncertainty froze business expansion plans. These frictions meant job losses were widespread, not only at weak firms but also at many solid firms that normally might have hired laid-off workers but couldn’t.

The result? Aggregate productivity growth actually dipped around 2008-2010, despite what the cleansing hypothesis might predict. Productivity-enhancing reallocation declined compared to previous recessions, and the U.S. experienced a puzzling productivity slowdown in the following decade.

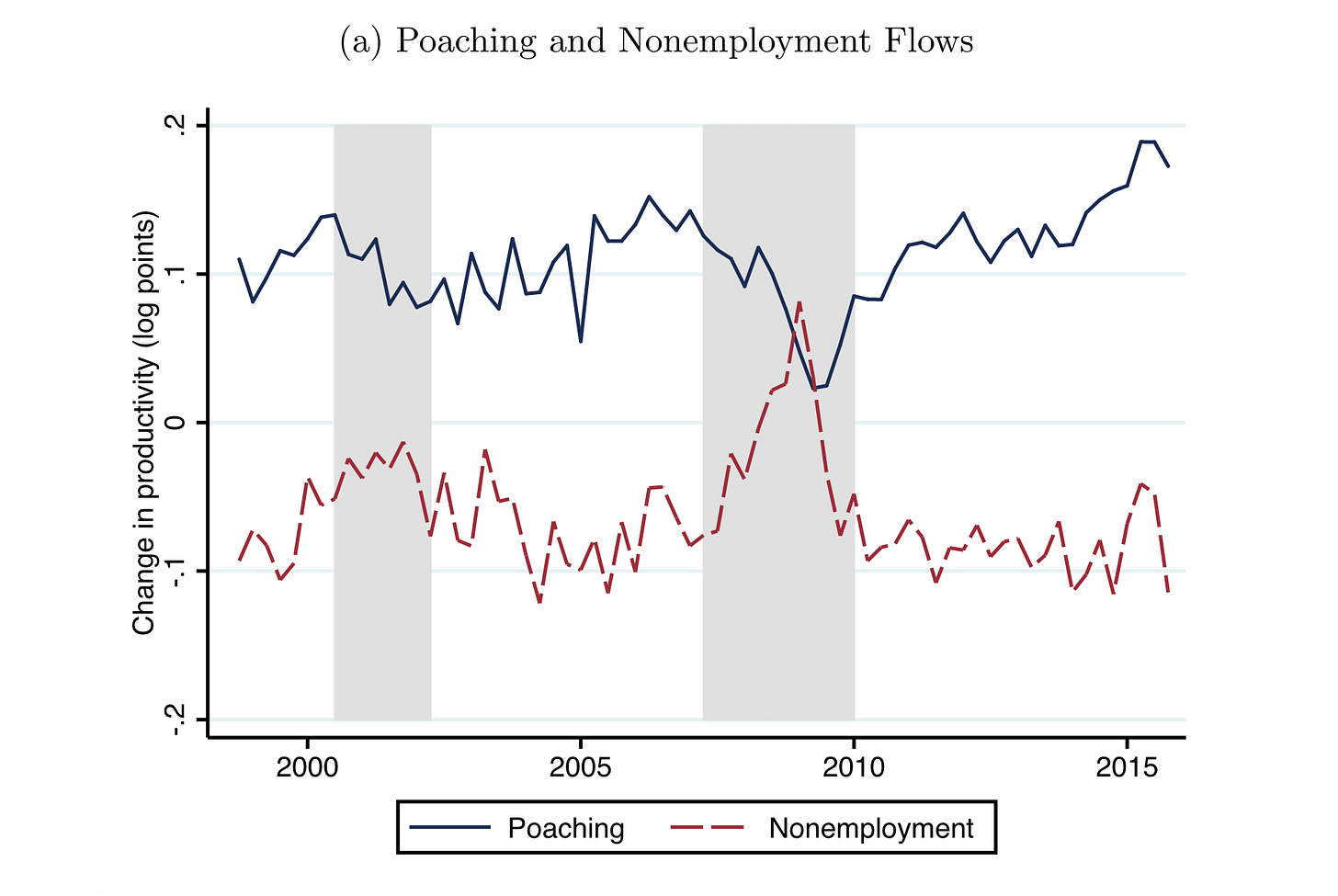

In a more recent paper, Haltiwanger, Hyatt, McEntarfer, and Staiger (2025) track worker movements between firms and find that in normal times, the economy benefits substantially from “job ladder” dynamics. High-productivity businesses systematically poach workers from lower-productivity firms, with the data showing clear patterns of upward mobility. These job-to-job flows contribute approximately 0.1 percentage points to quarterly productivity growth, which is a huge amount when compounded over years.

The microdata helps us see how recessions affect these reallocation patterns. When a downturn hits, two opposing forces immediately activate: The job ladder collapses as hiring freezes, with job-to-job moves plummeting during severe recessions. Simultaneously, layoffs surge, with the data showing they disproportionately hit low-productivity firms first. Their worker flow data quantifies these effects precisely. In the depths of the 2008-09 recession, the productivity boost from job-to-job transitions nearly vanished, while the contribution from layoffs (which were concentrated at less productive establishments) temporarily spiked to around 0.08 percentage points per quarter.

The Great Recession has so dominated our economic thinking that we risk overindexing to this single, unusual episode. The 2008 crisis was fundamentally a financial meltdown that paralyzed credit markets. These specific conditions severely disrupted the reallocation mechanisms that might otherwise have generated productivity benefits. By treating the 2008 experience as the template for all recessions, economists and policymakers may be overlooking important historical patterns. The best data shows that pre-2008 recessions did have meaningful cleansing effects. When we focus exclusively on 2008’s negative outcomes, we ignore this longer history and risk drawing overly broad conclusions about recessions in general. The mistake is not in recognizing that 2008 was harmful (it clearly was), but in assuming that all recessions must follow the same destructive path. Different types of downturns, with different origins and structures, can have substantially different effects on productivity and reallocation.

Were these real gains?

To determine whether recessions help or harm productivity, we need precise measurements. As a reminder, economists typically use two main metrics:

Labor productivity: Output per worker (or per hour)

Total factor productivity (TFP): A more comprehensive efficiency metric measuring output relative to a combination of inputs (labor, capital, etc.)

Foster, Grim, and Haltiwanger’s (2016) study on the Great Recession primarily uses an index of TFP at the establishment level, calculated relative to industry averages. This allows them to compare, for instance, how a factory performing 20% better than its industry average fares in a recession compared to one performing 20% below average.

Haltiwanger, Hyatt, McEntarfer, and Staiger rank firms by productivity using “real revenue per worker,” essentially inflation-adjusted sales per employee. This serves as a proxy for labor productivity. They then track how workers move between high-productivity and low-productivity firms during different phases of the business cycle.

Both papers are careful to distinguish between two kinds of productivity gains that can occur during a recession: mechanical compositional gains and genuine reallocation gains. This distinction is crucial, because rising average productivity during a downturn doesn’t necessarily mean the economy is becoming more efficient in any meaningful way.

A mechanical gain happens when low-productivity firms shrink or exit the market. By removing the least efficient producers, the average productivity of the surviving firms rises simply because the worst performers are gone. This is a statistical artifact, not a reflection of deeper improvement. Think of it like dropping the bottom of a grade distribution: the class average rises, but no one actually learned more.

By contrast, genuine reallocation gains occur when workers and other resources move from less productive to more productive firms. This kind of reallocation improves the efficiency of the economy as a whole, because the same inputs are now being used to produce more output. In Haltiwanger, Hyatt, McEntarfer, and Staiger (2025), this distinction plays out in the data as two types of worker flows: job-to-job transitions, where workers voluntarily move from lower- to higher-productivity employers (a clear sign of real allocative improvement), and separations to nonemployment, where workers leave low-productivity firms but do not immediately reenter the labor force. The latter raises average productivity mechanically (because weak firms shrink) but does not necessarily mean resources are being put to better use.

Policy-Induced Recessions: A Different Animal

Would a Trump-orchestrated recession raise productivity? Unlikely. It’s important to keep in mind that each recession is different. A crucial point in this discussion is that the recessions studied by Haltiwanger and other economists—even those showing some productivity benefits—weren’t deliberately engineered as economic “resets.” They certainly weren’t caused by whatever all this is *waves hands about at the past week of tariffs*.

This historical context matters because none of these downturns were designed with productivity enhancement as their goal. They weren’t orchestrated. In general, the pre-2008 recessions that showed stronger cleansing patterns emerged from specific external shocks that disproportionately affected less productive firms. They weren’t triggered by policies explicitly aiming to force a reordering of the economy.

The Volcker recession of the early 1980s represents an interesting intermediate case. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker deliberately tightened monetary policy to an extent that made a recession virtually inevitable. But crucially, Volcker wasn’t seeking a recession as an end in itself or as a means to restructure the economy. The singular aim was to break the back of inflation that had become entrenched at double-digit levels. The recession was a painful but accepted side effect of that anti-inflation fight, not the primary goal.

This distinction is important because the Volcker tightening, while severe, worked through broad-based channels that affected the entire economy. Interest rates rose for all borrowers, and demand contracted across sectors. Within this broadly-applied constraint, market forces could still operate to determine which firms survived and which failed. More efficient firms typically had stronger balance sheets and better cash flow, giving them better odds of weathering the storm. The data shows that during this period, job destruction was indeed concentrated among less productive establishments, consistent with a cleansing effect.

But even the Volcker recession differed fundamentally from what some officials are now suggesting with a tariff-induced downturn. Monetary policy works by tightening financial conditions economy-wide, allowing market forces to determine winners and losers within that constraint. A tariff-induced recession, by contrast, would directly distort relative prices across industries, potentially shielding inefficient domestic producers while punishing efficient ones that rely on global supply chains. This arbitrary reordering would likely impede, rather than enhance, the economy’s productive capacity.

The lesson from historical recessions is that when productivity benefits emerged, they came from the way downturns interacted with broader economic forces, not because recessions themselves were inherently cleansing. And certainly not because policymakers deliberately engineered downturns to restructure the economy. The idea that we can orchestrate a “good recession” to boost productivity fundamentally misunderstands both the historical evidence and the mechanisms through which productivity enhancement actually occurs.

Recessions Are Still Very Bad

Recessions impose enormous costs—on workers, families, and businesses—and there’s no guarantee that what emerges on the other side will be better. Yes, recessions can sometimes purge inefficiencies and prompt reforms. However, to label recessions “good” for the economy is an oversimplification at best and dangerous at worst. Evidence from the Great Recession shows downturns can just as easily hamper productivity as enhance it. The outcome depends entirely on the nature of the shock and policy response.

A recession might occasionally coincide with beneficial market adjustments, but these are blunt, destructive resets that create widespread suffering. The notion of an orchestrated recession fundamentally misunderstands economic history: intentional harm is not the same as creative destruction that happens throughout the business cycle. Deliberately engineering a downturn, particularly through distortionary policies like broad tariffs, let alone all the chaos of the past week, risks causing harm without the theoretical benefits proponents claim. Rather than leaping forward, such policies would likely leave the economy merely picking up pieces.

So "Liberation Day(s)" are here and the whole pile of pro Trump economics, business & financial writers have disappeared as they can't defend or even model the chaos of the last 30 days..

this is GFC & Covid on crack.. its like a daily TARP vote..

We have a "Negative Gamma" sell into a declines which is blasting our global financial economics, economy, business environment. We are stuck in "Buy the truth and sell the news" is our real world facts.. stuck in recession all man made...

Everyone knows this is demolishing earnings projections for 20,000 public trading companies, top 10,000 private firms in the world. These 30,000 firms are earth..These firms are 90% of earnings, 90% corporate taxes, 85% of trade, 90% of private R&D, 90% CapX, 85% technology spending, 90% Industrial investment, 60% of employees..

As these 30,000 firms cut their earning projections, hiring, investment, trade, taxes.. this will smash $10 trillions out of the global economy.

Then the largest 1000 banks & 5000 financial firms in the world which drive $100s of trillions of financial flows across equities, credit, currency, trade, payments, swaps, financial products, pensions, funds, etc.. they are very sensitive to massive change and will reduce $10s of trillions of transactions which will blast their balance sheets

This is "man made" train wreck recession but the hard right & pro Trump wing are stuck as they have zero answers as team Trump is blowing up the global economy..

Outside of all of this everything is great.. can't wait to see the pro Trump & hard right defense of this in their economics & financial opinion pieces..

I love this summary, thank you. The Jan 25 paper looks at the productivity effects within each industry. But recessions cause shifts in industrial composition. Do they look at that? We’ve become more service oriented and less manufacturing. Every time factories close in a recession, the new ones opens up abroad, not in the US. Not the same for restaurants and delivery drivers.

Since the industry shares have changed so much over time, it’s difficult to compare episodes